Adult Gynecology: Reproductive Years

Bs. Nguyễn Hồng Anh

KEY POINTS

1 The causes of abnormal bleeding vary by age, with anovulatory bleeding most likely

in adolescents and perimenopausal women.

2 Anatomic causes of abnormal bleeding including endometrial polyps and leiomyoma

occur more frequently in women of reproductive age than in women in other age

465groups

3 Pelvic masses in adolescents and women of reproductive age are most commonly

functional or benign neoplastic ovarian masses, whereas the risks of malignant

ovarian tumors increase with age.

4 Although pelvic ultrasonography is an excellent technique for imaging pelvic masses

and ultrasonographic characteristics may suggest reassuring characteristics of an

ovarian mass, the possibility of malignancy must be kept in mind.

5 Most uterine leiomyomas are asymptomatic, although bleeding, pressure symptoms,

or pain may necessitate medical or surgical management.

Benign gynecologic conditions can present with signs and symptoms that vary by

age. In this chapter, the most likely causes of specific signs and symptoms,

diagnosis, and management are described for reproductive age and

postmenopausal women. Common gynecologic problems include those that

cause pain and bleeding, such as pelvic masses (which may be symptomatic

or asymptomatic), and vulvar and vaginal symptoms. Benign conditions of the

female genital tract include anatomic lesions of the uterine corpus and cervix,

ovaries, fallopian tubes, vagina, and vulva. A classification of benign lesions of

the vulva, vagina, and cervix appears in Table 10-1. Leiomyoma, polyps, and

hyperplasia are the most common benign conditions of the uterus in adult women.

Benign uterine leiomyoma (uterine fibroids) are presented in Chapter 11. Benign

tumors of the ovaries are listed in Table 10-2. Malignant diseases are presented in

Chapters 37 to 42. Pediatric and adolescent conditions are discussed in Chapter 9.

Table 10-1 Classification of Benign Conditions of the Vulva, Vagina, and Cervix

Vulva

Skin conditions

Pigmented lesions

Tumors and cysts

Ulcers

Nonneoplastic epithelial disorders

Vagina

Embryonic origin

Mesonephric, paramesonephric, and urogenital sinus cysts

466Adenosis (related to in utero diethylstilbestrol exposure)

Vaginal septa or duplications

Pelvic organ prolapse/disorders of pelvic support

Anterior vaginal prolapse

Cystourethrocele

Cystocele

Apical vaginal prolapse

Uterovaginal

Vaginal vault

Posterior vaginal prolapse

Enterocele

Rectocele

Other

Condyloma

Urethral diverticula

Fibroepithelial polyp

Vaginal endometriosis

Cervix

Infectious

Condyloma

Herpes simplex virus ulceration

Chlamydial cervicitis

Other cervicitis

Other

467Endocervical polyps

Nabothian cysts

Columnar epithelium eversion

Table 10-2 Benign Ovarian Tumors

Functional

Follicular

Corpus luteum

Theca lutein

Inflammatory

Tubo-ovarian abscess or complex

Neoplastic

Germ cell

Benign cystic teratoma

Other and mixed

Epithelial

Serous cystadenoma

Mucinous cystadenoma

Fibroma

Cystadenofibroma

Brenner tumor

Mixed tumor

Other

Endometrioma

468REPRODUCTIVE AGE GROUP

Abnormal Bleeding

Normal Menses

After adolescence, menstrual cycles generally conform to a cycle length of 21

to 35 days, with the duration of menstrual flow fewer than 7 days (1). [1] As a

woman approaches menopause, the cycle length becomes more irregular

because fewer cycles are ovulatory (1,2). The most frequent cause of

irregular bleeding in the reproductive age group is hormonal, although other

causes such as pregnancy-related bleeding (spontaneous abortion, ectopic

pregnancy) should always be considered (Table 10-3). A variety of imprecise

terms such as menorrhagia or menometrorrhagia have been used to describe

abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB); it is strongly recommended that these

confusing terms be abandoned in favor of simple designations of menstrual

cycles, describing cycle regularity, frequency, duration, and heaviness of flow

(Table 10-4) (3,4). The International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

(FIGO) and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)

have recommended that systematized nomenclature, the PALM-COEIN acronym,

be used to describe abnormal menses (Table 10-5). The term dysfunctional

uterine bleeding (DUB) should no longer be used (3–6).

Prospective charting of bleeding can be helpful in characterizing abnormal

bleeding. The mean duration of menses is 4.7 days; 89% of cycles last 7 days

or longer. The average blood loss per cycle is 35 mL (6). Menses comprises a

suspension of blood- and tissue-derived solids within a mixture of serum and

cervicovaginal fluid; the blood content of menses varies over the days of

bleeding, but on average is close to 50% (7). Heavy menstrual bleeding is

defined as greater than 80 mL per day, which will result in anemia if recurrent (8).

Pregnancy-Related Bleeding

Pregnancy should always be excluded in women of reproductive age

presenting with AUB.

Table 10-3 Causes of Bleeding by Approximate Frequency and Age Group

469Spontaneous abortion can be associated with excessive or prolonged bleeding.

A woman may be unaware that she conceived and may seek care because of

abnormal bleeding. In the United States, nearly half of pregnancies are

unintended. These women may be at particular risk for bleeding related to an

unsuspected pregnancy. About one-half of unintended pregnancies result from

nonuse of contraception; the other one-half result from contraceptive failures (9).

[1] Unintended pregnancies are most likely to occur among adolescents and

women older than 40 years of age (see Chapter 14). If an ectopic pregnancy is

ruled out, the management of spontaneous abortion may include either

observation, if the bleeding is not excessive; medical or pharmacologic uterine

evacuation (with misoprostol); or surgical management with suction curettage or

dilation and curettage (D&C), depending on the clinician’s judgment and the

patient’s preference (10).

Differential Diagnosis of Abnormal Bleeding

Structural causes of AUB include the PALM in PALM-COEIN (Polyps,

Adenomyosis, Leiomyoma, Malignancy/Hyperplasia). [2] Anatomic causes of

abnormal bleeding occur more frequently in women of reproductive age than

in women in other age groups. [5] Uterine leiomyomas and endometrial

polyps are common conditions that most often are asymptomatic; however,

they remain important causes of abnormal bleeding (11).

Polyps, AUB-P

[2] Endometrial polyps are a cause of intermenstrual bleeding, heavy

menstrual bleeding, irregular bleeding, and postmenopausal bleeding. They

are associated with the use of tamoxifen and infertility, and can cause

dysmenorrhea. As with leiomyomas, most endometrial polyps are

asymptomatic. [2] The incidence of endometrial polyps increases with age

throughout the reproductive years (12). The diagnosis may be suspected on the

basis of endometrial thickening on transvaginal pelvic ultrasound, and vascular

470patterns of feeder blood vessels may aid in distinguishing endometrial polyps

from intracavity fibroids and from endometrial malignancy (13–15). Confirmation

of a polyp requires visualization with hysteroscopy, sonohysterography, or the

microscopic assessment of tissue obtained by a biopsy done in the office or with a

D&C. Whether and when to recommend removal is not well established,

particularly if a polyp is asymptomatic and is found incidentally. The effect of

polyps on fertility is not clear, though there is evidence that removal may improve

rates of pregnancy in infertile patients (16). One study of randomly selected

Danish women using transvaginal ultrasound and sonohysterography found

polyps in 5.8% of asymptomatic premenopausal women and 11.8% of

asymptomatic postmenopausal women. In this study, abnormal bleeding was

present in 38% of those without polyps versus 13% with polyps (15). Endometrial

polyps can regress spontaneously, although it is not clear how frequently this

occurs. In one study of asymptomatic women, the 1-year regression rate was 27%

(17). Smaller polyps are more likely to resolve, and larger polyps may be more

likely to result in abnormal bleeding (18). Whereas polyps may resolve

spontaneously over time, a clinically important question is whether they are likely

to undergo malignant transformation. Because even asymptomatic polyps are

usually removed at the time of identification, this question is difficult to answer.

[2] The chance of malignancy or premalignant changes in endometrial polyps

appears to be quite low in premenopausal women and higher among

postmenopausal women, with bleeding reports that range from 0.2% to 24% in

premalignant change and 0% to 13% in malignancy (16).

Table 10-4 Menstrual Terminology

Table 10-5 Abnormal Uterine Bleeding Terminology

Structural Causes PALM

AUB-P Polyp

AUB-A Adenomyosis

AUB-L Leiomyoma

471AUB-M Malignancy + Hyperplasia

Nonstructural COEIN

AUB-C Coagulopathy

AUB-O Ovulatory dysfunction

AUB-E Endometrial

AUB-I Iatrogenic

AUB-N Not yet classified

Adenomyosis, AUB-A

Traditionally adenomyosis has been diagnosed by histology at the time of

hysterectomy, making estimates of prevalence and contribution to AUB and

pelvic pain unclear. With improving imaging technology and evolving

diagnostic criteria for adenomyosis on ultrasound and MRI, adenomyosis

can be diagnosed prior to hysterectomy and is included as a structural cause

of abnormal bleeding. The incidence of incidentally identified adenomyosis on

pelvic imaging is not yet known (5).

Leiomyoma, AUB-L

[5] Uterine leiomyomas occur in as many as one-half of all women older than age

35 years and are the most common tumors of the genital tract (12). The incidence

varies from 30% to 70%, depending on the criteria for study, whether clinical

symptoms, ultrasound, or histologic assessment (11). One study of a randomly

selected population estimated a cumulative prevalence of greater than 80% in

black women and nearly 70% in white women based on ultrasound (19).

Abnormal bleeding is the most common symptom for women with leiomyomas

who are symptomatic. Although the number and size of uterine leiomyomas

do not appear to influence the occurrence of abnormal bleeding, submucosal

myomas are the most likely to cause bleeding. The mechanism of abnormal

bleeding related to leiomyomas is not well established (see Chapter 11 for further

discussion of uterine fibroids).

Malignancy and Hyperplasia, AUB-M

Unopposed estrogen is associated with a variety of abnormalities of the

endometrium, from cystic hyperplasia to adenomatous hyperplasia, hyperplasia

with cytologic atypia, and invasive carcinoma. Abnormal bleeding is the most

frequent symptom of women with invasive cervical cancer. A visible cervical

472lesion should be evaluated by biopsy rather than awaiting the results of cervical

cytology testing, because those results may be falsely negative with invasive

lesions as caused by tumor necrosis. Although vaginal neoplasia is uncommon,

the vagina should be evaluated carefully when abnormal bleeding is present.

Attention should be directed to all surfaces of the vagina, including anterior and

posterior areas that may be obscured by the vaginal speculum on examination.

Nonstructural causes of AUB include the COEIN in PALM-COEIN

(Coagulopathy, Ovulatory dysfunction, Endometrial, Iatrogenic, NOS)

Coagulopathy, AUB-C

As with adolescents, hematologic causes of abnormal bleeding should be

considered in women with heavy menstrual bleeding, particularly in those who

have had heavy bleeding since menarche. Of all women with menorrhagia, 5%

to 20% have a previously undiagnosed bleeding disorder, primarily the von

Willebrand disease (20). Table 10-6 presents guidelines for a gynecologist’s

suspicion of a bleeding disorder and pursuit of a diagnosis (21). Abnormal liver

function, which can be seen with alcoholism or other chronic liver diseases,

results in inadequate production of clotting factors and can lead to excessive

menstrual bleeding.

Ovulatory Dysfunction, AUB-O

[1] Most anovulatory bleeding results from what is termed estrogen

breakthrough. In the absence of ovulation and the production of progesterone, the

endometrium responds to estrogen stimulation with proliferation. This

endometrial growth without periodic shedding results in eventual breakdown of

the fragile endometrial tissue. Healing within the endometrium is irregular and

dyssynchronous. Relatively low levels of estrogen stimulation will result in

irregular and prolonged bleeding, whereas higher sustained levels result in

episodes of amenorrhea followed by acute, heavy bleeding.

Many ovulatory disorders relate to endocrine disturbances. Both

hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism can be associated with abnormal

bleeding. With hypothyroidism, menstrual abnormalities, including

menorrhagia, are common (see Chapter 35). The most common cause of

thyroid hyperfunctioning in premenopausal women is Graves’ disease, which

occurs four to five times more often in women than men. Hyperthyroidism

can result in oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, and it can lead to elevated

levels of plasma estrogen (22). Other causes of anovulation include

hypothalamic dysfunction, hyperprolactinemia, premature ovarian failure

(POF), and primary pituitary disease (Table 10-7). These conditions often

are considered causes of amenorrhea, but they may be the cause of irregular

473bleeding (see Chapter 34). The rare and unusual causes of abnormal bleeding

should not be overlooked. Women with primary ovarian insufficiency (POI;

previously termed POF) frequently see several clinicians with symptoms of

oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea prior to receiving a diagnosis; the diagnosis

of POI is often delayed during waning ovarian function and insufficiency

(23,24). POI is thought to occur in approximately 1 of 100 women by age 40, 1 of

1,000 women by age 30, and 1 of 10,000 women by age 20. Women should be

encouraged to track their menstrual cyclicity and to consider that the menstrual

cycle can be a “vital sign” that reflects the overall health (25).

Table 10-6 When Should a Gynecologist Suspect a Bleeding Disorder

Heavy menstrual bleeding since menarche

Family history of bleeding disorder

Personal history of any of the following:

Epistaxis in the last year

Bruising without injury >2-cm diameter

Minor wound bleeding

Oral or gastrointestinal bleeding without anatomic lesion

Prolonged or heavy bleeding after dental extraction

Unexpected postoperative bleeding

Hemorrhage from ovarian cyst

Hemorrhage requiring blood transfusion

Postpartum hemorrhage, especially delayed >24 h

Failure to respond to conventional management of menorrhagia

From James AH, Kouides PA, Abdul-Kadir R, et al. von Willebrand disease and other

bleeding disorders in women: Consensus on diagnosis and management from an

international expert panel. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2009;201:12e1–e8.

Table 10-7 Conditions Associated with Anovulation and Abnormal Bleeding

Eating disorders

474Anorexia nervosa

Bulimia nervosa

Excessive physical exercise

Chronic illness

Primary ovarian insufficiency—POI (previously termed premature ovarian failure

[POF])

Alcohol and other drug abuse

Stress

Thyroid disease

Hypothyroidism

Hyperthyroidism

Diabetes mellitus

Androgen excess syndromes (e.g., polycystic ovary syndrome [PCOS])

Diabetes mellitus can be associated with anovulation, obesity, insulin

resistance, and androgen excess. Androgen disorders are very common among

women of reproductive age and should be evaluated and managed accordingly.

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is present in 5% to 8% of adult women and

undiagnosed in many of them (26). Because androgen disorders are associated

with significant cardiovascular disease, the condition should be diagnosed

promptly and treated. This condition becomes of more immediate concern in

women of reproductive age because of concerns related to fertility. Management

of bleeding disorders associated with androgen excess consists of an appropriate

diagnostic evaluation followed by the use of oral contraceptives (in the absence of

significant contraindications or the desire for conception) or the use of insulinsensitizing agents, coupled with dietary and exercise modification (27,28).

Endometrial, AUB-E

In ovulatory cycles, the endometrium itself may contribute to abnormal or

heavy menstrual bleeding (AUB/HMB). There is evidence that deficiencies of

vasoconstrictors or excess of vasodilators may lead to heavy bleeding. Local

vasoconstrictors include endothelin-1 and prostaglandin F2alpha. Local

vasodilators include prostacyclin I2 and prostaglandin E2 (29). Inflammation and

475infection can affect the endometrium. Menorrhagia can be the first sign of

endometritis in women infected with sexually transmissible organisms.

Women with cervicitis, particularly chlamydial cervicitis, can experience

irregular bleeding and postcoital spotting (see Chapter 15). Cervical testing for

Chlamydia trachomatis should be considered, especially for adolescents, women

in their 20s, and women who are not in a monogamous relationship. Endometritis

can cause excessive menstrual flow. A woman who seeks treatment for

menorrhagia and increased menstrual pain and has a history of light-to-moderate

previous menstrual flow may have an upper genital tract infection or pelvic

inflammatory disease (PID) (endometritis, salpingitis, oophoritis). Occasionally,

chronic endometritis will be diagnosed when an endometrial biopsy is obtained

for evaluation of abnormal bleeding in a patient without specific risk factors for

PID.

Iatrogenic, AUB-I

Iatrogenic-Exogenous Hormones

Irregular bleeding that occurs while a woman is using contraceptive

hormones should be considered in a different context than bleeding that

occurs in the absence of exogenous hormone use. Breakthrough bleeding

during the first 1 to 3 months of oral contraceptive use occurs in as many as

30% to 40% of users; it should almost always be managed expectantly with

reassurance because the frequency of breakthrough bleeding decreases with

each subsequent month of use (30). Irregular bleeding can result from

inconsistent use (31,32). Other estrogen–progestin delivery systems, including the

contraceptive patch, vaginal ring, and intramuscular regimens, are associated with

irregular breakthrough bleeding. These nondaily contraceptive regimens may

promote successful use, making irregular bleeding a less important factor for

some women in assessing the balance of risks versus benefits (see Chapter 14).

The use of progestin-only methods—including depot medroxyprogesterone

acetate (DMPA), progestin-only pills, the contraceptive implant, and the

levonorgestrel intrauterine system (IUS)—is associated with relatively high rates

of initial irregular and unpredictable bleeding; rates of amenorrhea vary over time

and by method (33). Counseling about the frequent side effects of irregular

bleeding is imperative before initially prescribing these methods of contraception.

Women who do not believe that they can cope with irregular, unpredictable

bleeding may not be good candidates for these methods. Hormonal implants and

IUDs releasing progestins do offer significant benefits of high efficacy and ease

of use (34,35). The management of irregular bleeding with hormonal

contraceptive use can range from reassurance and initial expectant

476management to recommendations for a change in the hormonal delivery

system or regimen. The use of additional oral estrogen or combined oral

contraceptives for 10 to 20 days improves bleeding with both DMPA and the

subdermal levonorgestrel in some studies (36). The use of a 5- to 7-day course of

NSAIDs may result in decreased breakthrough bleeding (36). The development of

a better understanding of the mechanisms causing irregular bleeding will likely

result in more effective and acceptable management strategies (33).

Not all bleeding that occurs while an individual is using hormonal

contraception is a consequence of hormonal factors. In one study, women who

experienced irregular bleeding while taking oral contraceptives had a higher

frequency of C. trachomatis infection (37). Screening for sexually transmitted

infections (STIs) should be considered in women presenting with irregular

bleeding while using hormonal contraception.

Not Yet Classified, AUB-N

This includes causes of AUB not yet discovered and those rarer and lessunderstood causes, including myometrial hypertrophy and AV malformations (8).

Diagnosis of Abnormal Bleeding

For all women, the evaluation of excessive and abnormal menses includes a

thorough medical and gynecologic history, the exclusion of pregnancy, the

consideration of possible malignancy, and a careful gynecologic examination.

Abnormal bleeding, either intermenstrual or postcoital, can be caused by

cervical lesions. Bleeding can result from endocervical polyps and infectious

cervical lesions, such as condylomata, herpes simplex virus ulcerations,

chlamydial cervicitis, or cervicitis caused by other organisms. Other benign

cervical lesions, such as wide eversion of endocervical columnar epithelium or

nabothian cysts, may be detected on examination, but rarely cause bleeding.

For women of normal weight between the ages of approximately 20 and 35

years who do not have clear risk factors for STDs, have no signs of androgen

excess, are not using exogenous hormones, and have no other findings on

examination, management may be based on a clinical diagnosis. Additional

laboratory or imaging studies may be indicated if the diagnosis is not apparent on

the basis of examination and history.

Laboratory Studies

In any patient with heavy menstrual bleeding, an objective measurement of

hematologic status should be performed with a complete blood count to

detect anemia or thrombocytopenia. A pregnancy test should be performed

477to rule out pregnancy-related problems. A TSH level and chlamydia testing

should be considered. Because of the possibility of a primary coagulation

problem, screening coagulation studies should be ordered where appropriate

(Table 10-6). The consensus report of an international expert panel recommends

measurement of CBC, platelet count and function, PT, activated PTT, VWF

(measured with ristocetin cofactor activity and antigen, factor VIII), and

fibrinogen to be assessed in collaboration with a hematologist (38).

Imaging Studies

Women with abnormal bleeding who have a history consistent with chronic

anovulation, are obese, or older than 35 to 40 years of age, require further

evaluation. A pelvic ultrasonographic examination may be helpful in delineating

anatomic abnormalities if the examination results are suboptimal or if an ovarian

mass is suspected. A pelvic ultrasonographic examination is the best initial

technique for evaluating the uterine contour, endometrial thickness, and ovarian

structure (39,40). The use of a vaginal probe transducer allows assessment of

endometrial and ovarian disorders, particularly in women who are obese. Because

of variation in endometrial thickness with the menstrual cycle,

measurements of endometrial stripe thickness are significantly less useful in

premenopausal than postmenopausal women (41). Sonohysterography is

especially helpful in visualizing intrauterine problems such as polyps or

submucosal leiomyoma. Although these sonographic techniques are helpful in

visualizing intrauterine pathology, histologic evaluation is required to rule out

malignancy. Other techniques, such as CT scanning and MRI, are not as helpful

in the initial evaluation of causes of abnormal bleeding and should be reserved for

specific indications, such as exploring the possibility of other intra-abdominal

pathology or adenopathy. MRI can be a secondary step in evaluating the location

of uterine fibroids with relationship to the endometrial cavity, staging and

preoperative evaluation of endometrial cancer, detecting adenomyosis, and

delineating adnexal and ovarian pathology (42).

Endometrial Sampling

[1] Endometrial sampling should be performed to evaluate abnormal

bleeding in women who are at risk for endometrial pathology, including

polyps, hyperplasia, or carcinoma. Such sampling is mandatory in the

evaluation of anovulatory bleeding in women older than 45 or in younger

women who are obese, in those who do not respond to medical therapy or

those with a history of prolonged anovulation (10).

The technique of a D&C, which was previously used extensively for the

evaluation of abnormal bleeding, has now been largely replaced by

478endometrial biopsy in the office. The classic study in which a D&C was

performed before hysterectomy with the conclusion that less than one-half of the

endometrium was sampled in more than one-half of the patients led to questioning

the use of D&C for endometrial diagnosis (43,44). Hysteroscopy, either

diagnostic or operative, with endometrial sampling, can be performed either in the

office or operating room (45).

A number of devices are designed for endometrial sampling, including a

commonly used, inexpensive, disposable, flexible plastic sheath with an internal

plunger that allows tissue aspiration; disposable plastic cannulae of varying

diameters that attach to a manually locking syringe that allows the establishment

of a vacuum; and cannulae (both rigid metal and plastic) with tissue traps that

attach to an electric vacuum pump (Fig. 10-1). Several studies comparing the

adequacy of sampling using these devices with D&C showed a comparable ability

to detect abnormalities. It should be noted that these devices are designed to

obtain a tissue sample rather than a cytologic washing. The diagnostic accuracy of

endometrial biopsy for endometrial malignancy and hyperplasia is good, although

persistent bleeding should prompt further testing (46). Hysteroscopy with targeted

biopsies is more sensitive than a D&C in evaluating uterine pathology (29).

FIGURE 10-1 Devices used for sampling endometrium. Top: Kevorkian curette. Bottom:

Pipelle.

Management of Abnormal Bleeding

Attention should be directed to establishing a cause of abnormal bleeding. In

most cases, medical therapy is effective in managing abnormal bleeding and

should be attempted before surgical management. [1] Medical management

479with either combined hormonal contraceptives or progestins is the preferred

therapy of anovulatory bleeding in women of reproductive age (8). Progestinreleasing IUDs are effective in treating heavy menstrual bleeding and demonstrate

comparable benefits for the quality of life (47). It is argued that the IUD should

be offered prior to consideration of hysterectomy, as there are comparable

benefits on heavy menstrual bleeding and clear cost benefits (48). When

medical therapy fails in women with anovulatory uterine bleeding and without the

desire for future childbearing, the surgical options of endometrial ablation or

hysterectomy can be considered. Endometrial ablation is an efficient and costeffective alternative to hysterectomy, although this therapy may not be definitive,

with increasing rates of repeat ablation and hysterectomy over time (8). In women

with leiomyomas, hysterectomy provides a definitive cure. A variety of surgical

alternatives to hysterectomy are available to women with symptomatic uterine

leiomyomas (see Chapter 11).

Nonsurgical Management

Most bleeding problems, including anovulatory bleeding, can be managed

nonsurgically. Treatment with NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen and mefenamic acid,

decreases menstrual flow by 30% to 50%, but is less effective than tranexamic

acid, danazol, or levonorgestrel IUD (49). Antifibrinolytics, such as tranexamic

acid, are effective in reducing menstrual blood loss, and this indication was

approved by the FDA in late 2008 (50).

Hormonal management of abnormal bleeding can frequently control

excessive or irregular bleeding. The treatment of choice for anovulatory

bleeding is medical therapy with combined oral contraceptives or progestins

including the levonorgestrel IUD (5). Oral contraceptives are used clinically to

decrease menstrual flow, although supporting data from prospective clinical trials

are sparse (51). Low-dose oral contraceptives may be used by reproductive age

women without medical contraindications and during the perimenopausal years in

healthy nonsmoking women who have no major cardiovascular risk factors. The

benefits of menstrual regulation in such women often override the potential risks.

The medical treatment of acute abnormal bleeding in reproductive age women is

the same as that described for adolescents (see Chapter 9).

For patients in whom estrogen use is contraindicated, progestins, both oral

and parenteral, can be used to control excessive bleeding. Cyclic oral

medroxyprogesterone acetate, administered from day 15 or 19 to day 26 of the

cycle, reduces menstrual flow but offers no advantages over other medical

therapies, such as NSAIDs, tranexamic acid, danazol, or the levonorgestrel IUD;

progestin therapy for 21 days of the cycle reduces menstrual flow, although

women found the treatment less acceptable than the levonorgestrel IUD (52). The

480benefits of progestins to the patient with oligomenorrhea and anovulation include

a regular flow and the prevention of long intervals of amenorrhea, which may end

in unpredictable, profuse bleeding. This therapy reduces the risk of hyperplasia

resulting from persistent, unopposed estrogen stimulation of the endometrium.

Depot formulations of medroxyprogesterone acetate, oral progestins,

levonorgestrel IUDs, and combined oral contraceptives are used to establish

amenorrhea in women at risk of excessive bleeding (53). Oral, parenteral, or

intrauterine delivery of progestins is used in selected women with endometrial

hyperplasia or early endometrial cancer who wish to maintain their fertility or in

whom surgical risks are judged to be prohibitive (29). Continued monitoring with

repeated sampling is indicated. Danazol is effective in decreasing bleeding and

inducing amenorrhea; it is rarely used for ongoing management of abnormal

bleeding because of its androgenic side effects, including weight gain, hirsutism,

alopecia, and irreversible voice changes. GnRH analogs are used for short-term

treatment of abnormal bleeding, either alone or with add-back therapy consisting

of combined estrogen/progestogen or progestogen alone (54).

Surgical Therapy

The surgical management of abnormal bleeding should be reserved for

situations in which medical therapy is unsuccessful or is contraindicated.

Although sometimes appropriate as a diagnostic technique, D&C is

questionable as a therapeutic modality. One study reported a measured

reduction in menstrual blood loss for the first menstrual period only (55). Other

studies suggest a longer-lasting benefit (56).

The surgical options range from a variety of techniques for endometrial

ablation or resection, to hysterectomy or a variety of conservative surgical

techniques for the management of uterine leiomyoma, including

hysteroscopy with resection of submucous leiomyomas, laparoscopic and

robotic techniques of myomectomy, uterine artery embolization, and

magnetic resonance–guided focused ultrasonography ablation (see Chapters

26 and 27). The choice of procedure depends on the cause of bleeding, the

patient’s preferences, the physician’s experience and skills, the availability of

newer technologies, and a careful assessment of risks versus benefits based on the

patient’s medical condition, concomitant gynecologic symptoms or conditions,

and desire for future fertility. The assessment of the relative advantages, risks,

benefits, complications, and indications of these procedures is a subject of

ongoing clinical research. Various techniques of endometrial ablation were

compared with the gold standard of endometrial resection, and the evidence

suggests comparable success rates and complication profiles (57). The advantages

of techniques other than hysterectomy include a shorter recovery time and

481reduced early morbidity. Symptoms can recur or persist and repeat procedures or

subsequent hysterectomy may be required if conservative options are chosen.

Additional studies that include quality-of-life outcomes will be helpful.

Collaborative decision making, taking into account individual patient preferences,

should follow a thorough discussion of options, risks, and benefits (58,59). Much

is written about the psychological sequelae of hysterectomy, and some of the

aforementioned surgical techniques were developed in an effort to provide less

drastic management options. Most well-controlled studies suggest that, in the

absence of pre-existing psychopathology, indicated but elective surgical

procedures for hysterectomy have few, if any, significant psychological

sequelae (including depression) (see Chapters 23 and 27) (60,61).

Pelvic Masses

[3] Conditions diagnosed as a pelvic mass in women of reproductive age are

presented in Table 10-8.

Differential Diagnosis

It is difficult to determine the frequency of diagnoses of pelvic mass in women of

reproductive age because many pelvic masses are not treated with surgery.

Nonovarian or nongynecologic conditions may be confused with an ovarian

or uterine mass (Table 10-8). The frequency of masses found at laparotomy

has been studied, although the percentages are affected by varying

indications for surgery, indications for referral, type of practice (gynecologic

oncology vs. general gynecology), and patient populations (e.g., a higher

percentage of African Americans with uterine leiomyomas). Benign masses,

such as functional ovarian cysts or asymptomatic uterine leiomyoma,

typically do not require or warrant surgery (Table 10-9).

Table 10-8 Conditions Diagnosed as a Pelvic Mass in Women of Reproductive Age

Urinary

Full urinary bladder

Urachal cyst

Uterus

Sharply anteflexed or retroflexed uterus

Intraligamentous leiomyomas

482Pregnancy (with or without concomitant leiomyomas)

Intrauterine

Tubal

Abdominal

Ovarian or adnexal masses

Functional cysts

Neoplastic tumors

Benign

Malignant

Inflammatory masses

Tubo-ovarian complex

Diverticular abscess

Appendiceal abscess

Other

Matted bowel and omentum

Peritoneal cyst

Stool in sigmoid

Paraovarian or paratubal cysts

Less common conditions that must be excluded:

Pelvic kidney

Carcinoma of the colon, rectum, appendix

Carcinoma of the fallopian tube

Retroperitoneal tumors (anterior sacral meningocele)

Uterine sarcoma or other malignant tumors

Table 10-9 Causes of Pelvic Mass by Approximate Frequency and Age

483Age is an important determinant of the likelihood of malignancy. In one

study of women who underwent laparotomy for pelvic mass, malignancy was

seen in only 10% of those younger than 30 years of age, and most of these

tumors had low malignancy potential (62). The most common tumors found

during laparotomy for pelvic mass are mature cystic teratomas or dermoids

(seen in one-third of women younger than 30 years of age) and

endometriomas (approximately one-fourth of women 31 to 49 years of age)

(62).

Uterine Masses

Uterine leiomyomas, commonly termed uterine fibroids, are by far the most

common benign uterine tumors and are usually asymptomatic. Other benign

uterine growths, such as uterine vascular tumors, are rare. See Chapter 11 for

discussion of diagnosis, types and locations of fibroids, incidence, symptoms,

causes, natural history, pathology, and management.

Ovarian Masses

[3] During the reproductive years, the most common ovarian masses are benign.

Ovarian masses can be functional or neoplastic, and neoplastic tumors can be

benign or malignant. Functional ovarian masses include follicular and corpus

luteal cysts. About two-thirds of ovarian tumors are encountered during the

reproductive years. Most ovarian tumors (80% to 85%) are benign, and two-thirds

of these occur in women between 20 and 44 years of age. The chance that a

primary ovarian tumor is malignant in a patient younger than 45 years of

age is less than 1 in 15. Most tumors produce few or only mild, nonspecific

symptoms. The most common symptoms include abdominal distention,

abdominal pain or discomfort, lower abdominal pressure sensation, and urinary or

gastrointestinal symptoms. If the tumor is hormonally active, symptoms of

hormonal imbalance, such as vaginal bleeding related to estrogen production, may

be present. Acute pain may occur with adnexal torsion, cyst rupture, or bleeding

into a cyst. Pelvic findings in patients with benign and malignant tumors may

484differ. Masses that are unilateral, cystic, mobile, and smooth are most likely to be

benign, whereas those that are bilateral, solid, fixed, irregular, and associated with

ascites, cul-de-sac nodules, and a rapid rate of growth are more likely to be

malignant (63).

In assessing ovarian masses, the distribution of primary ovarian neoplasms by a

decade of life can be helpful. Ovarian masses in women of reproductive age are

most likely benign, but the possibility of malignancy must be considered (Fig. 10-

2).

FIGURE 10-2 Preoperative evaluation of the patient with an adnexal mass.

Nonneoplastic Ovarian Masses

[3] Functional ovarian cysts include follicular cysts, corpus luteum cysts, and

theca lutein cysts. All are benign and usually do not cause symptoms or

require surgical management. Cigarette and marijuana smoking are associated

486with an increased risk of functional cysts, although the increased risk may be

attenuated in overweight or obese women (64). Oral contraceptive use is

associated with a decreased risk of developing functional ovarian cysts,

although low-dose pills may have a smaller benefit. Oral contraceptives do

not hasten the resolution of ovarian cysts (65,66). The annual rate of

hospitalization for functional ovarian cysts is estimated to be as high as 500 per

100,000 woman-years in the United States, although little is known about the

epidemiology of the condition. [3] The most common functional cyst is the

follicular cyst, which is rarely larger than 8 cm. A cystic follicle can be defined

as a follicular cyst when its diameter is greater than 3 cm. These cysts usually are

found incidental to pelvic examination or pelvic imaging, although they may

rupture or torse, causing pain and peritoneal signs. They typically resolve in 4 to 8

weeks with expectant management (66).

Corpus luteum cysts are less common than follicular cysts. Corpus luteum

cysts may rupture, leading to a hemoperitoneum and requiring surgical

management. Patients taking anticoagulant therapy or with bleeding diatheses are

at particular risk for hemorrhage and rupture. Rupture of these cysts occurs more

often on the right side and may occur during intercourse. Most ruptures occur

on cycle days 20 to 26 (67). Unruptured corpus luteum cysts can cause pain,

presumably because of bleeding into the enclosed ovarian cyst cavity. They can

produce symptoms and be difficult to discern from adnexal torsion.

Theca lutein cysts are the least common of functional ovarian cysts. They

are usually bilateral and occur with pregnancy, including molar pregnancies.

They may be associated with multiple gestations, molar pregnancies,

choriocarcinoma, diabetes, Rh sensitization, clomiphene citrate use, human

menopausal gonadotropin–human chorionic gonadotropin ovulation induction,

and the use of GnRH analogs. Up to one-quarter of complete molar pregnancies

will have theca lutein cysts which will regress spontaneously (68).

Combination monophasic oral contraceptive therapy is reported to reduce

the risk of developing functional ovarian cysts by suppression of both

follicular development and ovulation (69). It appears that, in comparison with

previously available higher-dose pills, the effect of cyst suppression with lowdose oral contraceptives is attenuated. The use of triphasic oral contraceptives is

not associated with an appreciable increased risk of functional ovarian cysts.

Other Benign Masses

Women with endometriosis may develop ovarian endometriomas (“chocolate”

cysts), which can enlarge from 6 to 8 cm in size. A mass that does not resolve

with observation may be an endometrioma (see Chapter 13). Excision of

endometriosis is preferable to ablative techniques with regard to achievement of

487spontaneous pregnancy (70). New data suggests that women with or without

endometriomas have similar success with conceiving when using ART and do not

need removal prior to fertility treatment if asymptomatic and the diagnosis is not

in question (71,72).

Although enlarged, polycystic ovaries were originally considered the sine qua

non of PCOS, and are included among the Rotterdam diagnostic criteria; they are

not always present with other features of the syndrome (73,74). An enlarged

ovarian volume is suggested as an alternative diagnostic criterion, although what

the threshold should be has been debated (75). The 2003 Rotterdam consensus

uses a volume greater than 10 mL in either ovary or 12 or more subcentimeter

antral follicles in either ovary (74).

The prevalence of PCOS among the general population depends on the

diagnostic criteria used. In one study, 257 volunteers were examined with

ultrasonography; 22% were found to have polycystic ovaries (76). The finding of

generously sized ovaries on examination or polycystic ovaries on

ultrasonographic examination should prompt evaluation for the full-blown

syndrome, which includes hyperandrogenism, chronic anovulation, and polycystic

ovaries (26). Therapy for PCOS is generally medical rather than surgical, with

lifestyle modification and weight loss playing a potentially important role (77).

Neoplastic Masses

[3] Most benign cystic teratomas (dermoid cysts) occur during the

reproductive years in adolescents and young women, although dermoid cysts

have a wider age distribution than other ovarian germ cell tumors; in some

case series, up to 25% of dermoids occur in postmenopausal women, and

they can occur in newborns (78). [3] Histologically, benign cystic teratomas

have an admixture of elements (Fig. 10-3). Malignant transformation occurs in

less than 2% of dermoid cysts in women of all ages; most cases occur in women

older than 40 years of age. The risk of torsion with dermoid cysts is

approximately 15%, and occurs more frequently than with other ovarian tumors,

perhaps because of the high fat content of most dermoid cysts, allowing them to

float within the abdominal and pelvic cavity. As a result of this fat content, on

pelvic examination a dermoid cyst frequently is described as anterior in location.

They are bilateral in approximately 10% of cases, although many have advanced

the argument against bivalving a normal-appearing contralateral ovary because of

the risk of adhesions, which may result in infertility. An ovarian cystectomy is

almost always possible, even if it appears that only a small amount of ovarian

tissue remains. Preserving a small amount of ovarian cortex in a young patient

with a benign lesion is preferable to the loss of the entire ovary (79).

Laparoscopic cystectomy often is possible, and intraoperative spill of tumor

488contents is rarely a cause of complications, although granulomatous peritonitis

has been reported (80). A minimally invasive, fertility-sparing approach is

preferred for benign masses (81).

[3] The risk of epithelial tumors increases with age. Although serous

cystadenomas are often considered the more common benign neoplasm, in one

study, benign cystic teratomas represented 66% of benign tumors in women

younger than 50 years of age; serous tumors accounted for only 20% (82). Serous

tumors are generally benign; 5% to 10% have borderline malignant

potential, and 20% to 25% are malignant. The major risk factor for ovarian

cancer is a family history of ovarian cancer or a familial syndrome,

particularly BRCA1 mutation (approx. 40% risk), BRCA2 mutation (15%

risk) or the Lynch syndrome (5% risk) (81).

Serous cystadenomas are often multilocular, sometimes with papillary

components (Fig. 10-4). The surface epithelial cells secrete serous fluid, resulting

in a watery cyst content. Psammoma bodies, which are areas of fine calcific

granulation, may be scattered within the tumor and are visible on the radiograph.

A frozen section is necessary to distinguish between benign, borderline, and

malignant serous tumors because this distinction cannot be made on gross

examination alone. Mucinous ovarian tumors may grow to large dimensions.

Benign mucinous tumors typically have a lobulated, smooth surface, are

multilocular, and may be bilateral in up to 10% of cases. Mucoid material is

present within the cystic loculations. Five to 10% of mucinous ovarian tumors

are malignant (see Chapter 39). They may be difficult to distinguish

histologically from metastatic gastrointestinal malignancies. Other benign ovarian

tumors include fibromas (a focus of stromal cells), Brenner tumors (which appear

grossly similar to fibromas and are frequently found incidentally), and mixed

forms of tumors, such as the cystadenofibroma.

FIGURE 10-3 Mature cystic teratoma (dermoid cyst) of the ovary.

FIGURE 10-4 Serous cystadenoma.

Uterine, gastric, breast, and colorectal malignancies can metastasize to the

ovaries and should be considered, although as with many malignancies, these

tumors are more common in postmenopausal-aged women.

Other Adnexal Masses

[3] Masses that include the fallopian tube are related primarily to

inflammatory causes in the reproductive age group. A tubo-ovarian abscess

can be present in association with PID (see Chapter 15). A complex inflammatory

mass consisting of the bowel, tube, and ovary may be present without a large

abscess cavity. Ectopic pregnancies can occur in the reproductive age group and

must be excluded when a patient presents with pain, a positive pregnancy test,

and an adnexal mass (see Chapter 32). Paraovarian cysts may be noted on

examination or in imaging studies. In many instances, a normal ipsilateral ovary

can be visualized using ultrasonography. The frequency of malignancy in

paraovarian tumors is quite low and may be more common in paraovarian masses

larger than 5 cm (83).

491Diagnosis of Pelvic Masses

A complete pelvic examination, including rectovaginal examination and

Papanicolaou (Pap) test, should be performed. Estimations of the size of a mass

should be presented in centimeters rather than in comparison to common

objects or fruit (e.g., orange, grapefruit, tennis ball, golf ball). After pregnancy is

excluded, one simple office technique that can help determine whether a mass is

uterine or adnexal includes sounding and measuring the depth of the uterine

cavity. Pelvic imaging can confirm the characteristics of the adnexal mass—

whether solid or cystic or mixed echogenicity. Diagnosis of uterine leiomyomas

usually is based on the characteristic finding of an irregularly enlarged uterus. The

size and location of the usually multiple leiomyomas can be confirmed and

documented with pelvic ultrasonography (Fig. 10-5). If the examination is

adequate to confirm uterine leiomyoma and symptoms are absent,

ultrasonography is not always necessary unless an ovarian mass cannot be

excluded. A fixed or nodular pelvic mass should always raise concern for

malignancy.

FIGURE 10-5 Transvaginal pelvic ultrasound demonstrating multiple uterine leiomyomas.

Other Studies

Endometrial sampling with an endometrial biopsy or hysteroscopy is

492mandatory when both pelvic mass and abnormal bleeding are present. An

endometrial lesion—carcinoma or hyperplasia—may coexist with a benign mass

such as a leiomyoma. In a woman with leiomyomas, abnormal bleeding cannot be

assumed to be caused solely by the fibroids. Clinicians differ in recommendations

about the need for endometrial biopsy when the diagnosis is leiomyomas with

regular menses.

If urinary symptoms are prominent, studies of the urinary tract may be

necessary, including urodynamic testing, if incontinence or symptoms of pelvic

pressure are present. Cystoscopy may be necessary or appropriate to rule out

intrinsic bladder lesions.

Laboratory Studies

Laboratory studies that are indicated for women of reproductive age with a pelvic

mass include pregnancy test, cervical cytology, and complete blood count. The

value of tumor markers, such as CA125 in distinguishing malignant from benign

adnexal masses in premenopausal women with a pelvic mass, is questioned. A

number of benign conditions, including uterine leiomyomas, PID, pregnancy,

and endometriosis can cause elevated CA125 levels in premenopausal

women; thus, measurement of CA125 levels is not as useful in

premenopausal women with adnexal masses. Values greater than 200 in a

premenopausal female may warrant gynecologic-oncology comanagement or

referral (81). Ultrasonographic characteristics are more helpful than CA125

in suggesting risks of malignancy in premenopausal women (84).

Imaging Studies

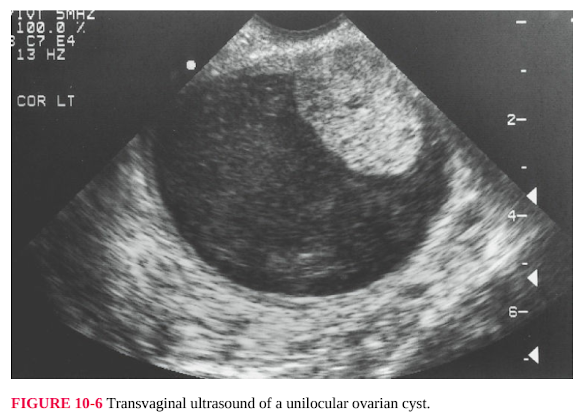

Other studies may be necessary or appropriate. [4] The most commonly indicated

study is pelvic ultrasonography, which will help document the origin of the mass

to determine whether it is uterine, adnexal, bowel, or gastrointestinal. The

ultrasonographic examination provides information about the size of the mass and

its consistency—unilocular cyst, mixed echogenicity, multiloculated cyst, or solid

mass—which can help determine management (Figs. 10-6 and 10-7). Size greater

than 10 cm, solid components, irregularity, papillary excrescences, and ascites

increase the suspicion of malignancy (81). A number of different ultrasound

scoring systems were developed in an effort to quantify the risks of malignancy.

FIGURE 10-6 Transvaginal ultrasound of a unilocular ovarian cyst.

FIGURE 10-7 Transvaginal ultrasonogram of a complex, predominantly solid mass.

[4] Transvaginal and transabdominal ultrasonography are complementary in the

diagnosis of pelvic masses, particularly those that have an abdominal component.

Transvaginal ultrasonography has the advantage of providing additional

information about the internal architecture or anatomy of the mass.

Heterogeneous pelvic masses, described as tubo-ovarian abscesses on

transabdominal ultrasonography, can be differentiated as pyosalpinx,

hydrosalpinx, tubo-ovarian complex, and tubo-ovarian abscess with transvaginal

ultrasonography (Fig. 10-8).

The diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal ultrasonography in diagnosing

endometrioma can be quite high (Fig. 10-9). Endometriomas can have a variety

of ultrasonographic appearances, from purely cystic to varying degrees of

complexity with septation or debris to a solid appearance. A variety of scoring

systems were developed with the intent of predicting benign versus malignant

adnexal masses using ultrasound; the ultrasonographic morphologic

characteristics used in many types of scoring systems are listed in Table 10-10

(81). Color flow Doppler was added to other sonographic characteristics to

predict the risk of malignancy; ultrasound techniques are comparable to CT and

MRI in differentiating benign from malignant masses (81,85). Although an

495analysis of such features may be helpful, histologic confirmation of surgically

removed persistent masses remains the standard of care.

FIGURE 10-8 Transvaginal ultrasonogram of bilateral tubo-ovarian abscesses.

FIGURE 10-9 Transvaginal ultrasonogram of an endometrioma of the ovary.

CT seldom is indicated as a primary diagnostic procedure, although it may be

helpful in planning treatment when a malignancy is strongly suspected or when a

nongynecologic disorder may be present. Abdominal flat-plate radiography is not

a primary diagnostic procedure, although if used for other indications, it may

reveal calcifications that can assist in the discovery or diagnosis of a mass. Pelvic

calcifications (teeth) consistent with a benign cystic teratoma, a calcified uterine

fibroid, or scattered calcifications consistent with psammoma bodies of a

papillary serous cystadenoma can be seen with abdominal radiography (Fig. 10-

10).

FIGURE 10-10 Benign cystic teratoma (dermoid cyst) of the ovary with teeth seen on

abdominal radiograph.

Ultrasonography or CT imaging may be appropriate to demonstrate ureteral

deviation, compression, or dilation in the presence of moderately large and

laterally located fibroids or other pelvic mass. Such findings rarely provide an

indication for surgical intervention for otherwise asymptomatic leiomyomas.

Table 10-10 Ultrasonographic Characteristics of Adnexal Masses That May Be Useful

in Predicting Malignancy

Unilocular cyst vs. multilocular vs. solid components

Regular contour vs. irregular border

Smooth walls vs. nodular vs. irregular

Presence or absence of ascites

Unilateral vs. bilateral

498Wall thickness

Internal echogenicity and septations (including thickness)

Presence of other intra-abdominal pathology (liver, etc.)

Vascular characteristics and color flow Doppler pattern

Hysteroscopy provides direct evidence of intrauterine pathology or

submucous leiomyomas that distort the uterine cavity (see Chapter 26).

Hysterosalpingography will demonstrate indirectly the contour of the endometrial

cavity and any distortion or obstruction of the uterotubal junction secondary to

leiomyomas, an extrinsic mass, or peritubal adhesions. The techniques combining

hysterosalpingography, in which fluid is instilled into the uterine cavity, with

transvaginal ultrasonography are helpful in the diagnosis of intrauterine

pathology. Hysterosalpingography or sonohysterography may be indicated in

women with infertility and uterine leiomyoma.

MRI may be most useful in the diagnosis of uterine anomalies, although its

value rarely justifies the increased cost of the procedure over ultrasonography for

the diagnosis of other pelvic masses (86).

Management of Pelvic Mass

The management of a pelvic mass is based on an accurate diagnosis. An

explanation of this diagnosis should be conveyed to the patient, along with a

discussion of the likely course of the disease (e.g., growth of uterine leiomyomas,

regression of fibroids at menopause, regression of a follicular cyst, the uncertain

malignant potential of an ovarian mass). All options for management should be

presented and discussed, although it is appropriate for the physician to state a

recommended approach with an explanation of the reasons for the

recommendation. Management should be based on the primary symptoms and

may include observation with close follow-up, temporizing surgical therapies,

medical management, or definitive surgical procedures.

Leiomyomas

[5] The management of uterine leiomyomas is dependent on the patient’s age and

proximity to anticipated menopause, symptoms, patient preference, and the

experience and skills of the clinician. Variability in reporting data regarding the

severity of symptoms, uterine anatomy, and response to therapy makes it difficult

to compare different types of therapies, which include observation, medical,

surgical, and radiologic-based techniques (see Chapter 11 for discussion of

uterine fibroids).

499Ovarian Masses

The now-routine application of ultrasound technology to gynecologic

examinations led to the more frequent detection of ovarian cysts, sometimes as an

incidental finding. Ultrasonography is a relatively easy diagnostic study to

perform, but this ease led to the labeling of physiologic ovarian morphology and

cystic follicles, as pathologic and the subsequent referral of patients for therapies,

including surgery, without indications. Treatment of ovarian masses that are

suspected to be functional tumors is expectant (Fig. 10-2). A number of

randomized prospective studies showed no acceleration of the resolution of

functional ovarian cysts (some of which were associated with the use of

clomiphene citrate or human menopausal gonadotropins) with oral

contraceptives compared with observation alone (66). Oral contraceptives

are effective in reducing the risk of subsequent ovarian cysts and may be

appropriate for women who desire both contraception and their

noncontraceptive benefits.

Symptomatic cysts should be evaluated promptly, although mildly

symptomatic masses suspected to be functional should be managed with

analgesics rather than surgery to avoid the risk of surgical complications,

including the development of adhesions that may impair subsequent fertility.

Surgical intervention is warranted in the presence of severe pain or the suspicion

of malignancy or torsion.

[4] On ultrasonography, ascites, cysts greater than 10 cm and those that have

multiloculations are concerning for malignancy (81). If a malignant mass is

suspected at any age, surgical evaluation should be performed promptly.

Simple cysts up to 10 cm in size are likely benign and can be managed

expectantly at any age, if asymptomatic (81).

Ovarian or adnexal torsion is suspected on the basis of peritoneal signs and the

acuity of onset, often accompanied by nausea and vomiting. Doppler flow studies

suggesting abnormal flow are predictive of torsion, although torsion can be seen

with normal flow (87). The absence of internal ovarian flow is not specific to

torsion and may be seen with cystic lesions, although in these situations

peripheral flow usually can be visualized.

The management of suspected ovarian torsion, which can occur at any age

from prepubertal to postmenopausal, is surgical. When torsion is confirmed

by laparoscopy, untwisting of the mass and ovarian preservation rather than

extirpation are generally indicated (88). The value of oophoropexy in

preventing recurrent torsion is not well established.

Ultrasonographic or CT-directed aspiration procedures of ovarian masses

should not be used in women in whom there is a suspicion of malignancy. In

the past, laparoscopic surgery for ovarian masses was reserved for diagnostic or

500therapeutic purposes in patients at very low risk for malignancy. With the recent

advancements in minimally invasive surgery the current recommendation is for

laparoscopic management of suspected benign adnexal masses (Fig. 10-11),

even those greater than 10 cm. Rates of intraoperative rupture were found to be

similar between the open and laparoscopic approaches in three randomized trials

made up of 394 patients. The benefits of laparoscopy included decreased

operative time, hospital stay, postoperative pain, and perioperative morbidity. The

conversion rate to laparotomy was less than 2% (81).

FIGURE 10-11 Laparoscopic appearance of benign ovarian mass (dermoid cyst).

Vulvar Conditions

In postmenarchal individuals, vulvar symptoms are most often related to a

primary vaginitis and a secondary vulvitis. The mere presence of vaginal

discharge can lead to vulvar irritative symptoms, or candidal vulvitis may be

present (Fig. 10-12). The causes of vaginitis and cervicitis are covered in Chapter

15. Adult women describe vulvar symptoms using a variety of terms (itching,

pain, discharge, discomfort, burning, external dysuria, soreness, pain with

501intercourse or sexual activity). Burning with urination from noninfectious

causes may be difficult to distinguish from a urinary tract infection, although

some women can distinguish pain when the urine hits the vulvar area (an

external dysuria) from burning pain (often suprapubic in location) during

urination. Itching is a very common vulvar symptom. A variety of vulvar

conditions and lesions can present with pruritus. Vulvovaginal symptoms may be

caused by STDs, nonsexually transmitted vaginitis, or UTIs. The distinction

between symptoms related to a UTI and those of vaginitis is difficult, and

consideration should be given to testing for both C. trachomatis and obtaining a

urine culture, particularly in young reproductive age women (89).

FIGURE 10-12 Candidal vulvitis.

A number of skin conditions that occur on other areas of the body may occur

on the vulvar area. Table 10-11 contains a list of these conditions classified by

either infectious or noninfectious causes. Whereas the diagnosis of some of these

conditions is apparent from inspection alone (e.g., a skin tag), any lesions that

appear atypical or in which the diagnosis is not clear should be analyzed by

502biopsy, because the risks of malignant lesions increases with age (Fig. 10-13).

Pigmented vulvar lesions include benign nevi, lentigines, melanosis, seborrheic

keratosis, condyloma, and some vulvar intraepithelial neoplasias (VINs),

especially multifocal VIN-3 (Fig. 10-14). Suspicious pigmented vulvar lesions

in particular should warrant biopsy to rule out VIN or malignant melanoma

(90). Approximately 10% of white women have a pigmented vulvar lesion; some

of these lesions may be malignant (see Chapter 40) or have the potential for

progression (VIN) (see Chapter 16). There is an increase in rates of VIN in

women younger than age 50, along with increasing rates of vulvar squamous cell

carcinoma in situ, possibly related to increasing rates of human papillomavirus

(HPV) infection. Heightened awareness among clinicians may play a role in the

increasing frequency of diagnosis; suspicious lesions warrant vulvar biopsy.

Pigmented lesions include common nevi, lentigines, melanomas, dysplastic nevi,

blue nevi, and a lesion termed atypical melanocytic nevi of the genital type

(AMNGT) (91). AMNGTs have some histologic features that may overlap with

those of melanoma, but with a benign prognosis.

Table 10-11 Subacute and Chronic Skin Recurrent Conditions of the Vulva

Noninfectious Infectious

Acanthosis nigricans Cellulitis

Atopic dermatitis Folliculitis

Behçet disease Furuncle/carbuncle

Contact dermatitis Insect bites (e.g., chiggers, fleas)

Crohn disease Necrotizing fasciitis

Diabetic vulvitisa Pubic lice

Hidradenitis suppurativaa Scabies

Tinea

Lichen sclerosus Condyloma

Paget disease Vulvar candidiasis

“Razor bumps”—folliculitis or pseudofolliculitis HSV

Psoriasis

503Seborrheic dermatitis

Vulvar aphthous ulcer

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia

aEtiology unknown, often secondarily infected.

FIGURE 10-13 Large benign skin tag from left labium majus.

FIGURE 10-14 Pigmented vulvar lesion.

Vulvar Biopsy

A vulvar biopsy is essential for distinguishing benign from premalignant or

malignant vulvar lesions, especially because many types of lesions may have

a somewhat similar appearance. Vulvar biopsies should be performed liberally

in women of reproductive age to ensure that these lesions are diagnosed and

treated appropriately. A prospective study of vulvar lesions evaluated by biopsy

in a gynecologic clinic found lesions occurring in the following order of

frequency: epidermal inclusion cyst, lentigo, Bartholin duct obstruction,

carcinoma in situ, melanocytic nevi, acrochordon, mucous cyst, hemangiomas,

postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, seborrheic keratoses, varicosities,

hidradenomas, verruca, basal cell carcinoma, and unusual tumors such as

neurofibromas, ectopic tissue, syringomas, and abscesses (92). The frequency

with which a lesion would be reported after a tissue biopsy is related to the

frequency with which all lesions of a given pathology are evaluated in this

manner. This listing probably underrepresents such common lesions as

condylomata (Fig. 10-15).

FIGURE 10-15 Extensive vulvar condyloma.

Biopsy is easily performed in the office using a local anesthetic. Typically,

1% lidocaine is infiltrated beneath the lesion using a small (25- to 27-gauge)

needle. Disposable punch biopsy instruments come in a variety of sizes from 2 to

6 mm in diameter. These skin biopsy instruments, along with fine forceps,

scissors, and a scalpel, should be available in all outpatient gynecologic settings.

For smaller biopsies, it is usually not necessary to place a suture. Topical silver

nitrate can be used for hemostasis. Multiple tissue samples may be appropriate to

obtain representative areas of a lesion if the lesion has a variable appearance or is

multifocal. Although the vulvar biopsy procedure involves minimal discomfort

during the procedure, the biopsy sites will be painful for several days after the

procedure. The prescription of a topical anesthetic such as 2% lidocaine jelly, to

be applied periodically and before urinating, is appreciated by patients who

require this procedure. Infection of the site can occur, and patients should be

cautioned to report excessive erythema or purulent drainage.

Other Vulvar Conditions

506Classification and description of intraepithelial lesions of the vulva are presented

in Chapter 16.

Pseudofolliculitis or Mechanical Folliculitis

This is similar to what is described as pseudofolliculitis barbae (razor bumps) and

may occur in women who follow the popular practice of shaving pubic hair (93).

Pseudofolliculitis consists of an inflammatory reaction surrounding an

ingrown hair and occurs most commonly among individuals with curly hair,

particularly African Americans.

Infectious Folliculitis

Shaving may be associated with an infectious folliculitis, commonly caused by

Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes. Shaving and other methods

of pubic hair removal are associated with razor burn, contact dermatitis, and the

transmission of other infectious agents such as Molluscum contagiosum, HPV,

and herpes simplex along with other bacteria including Pseudomonas aeruginosa

(93).

Fox–Fordyce Disease

This condition is characterized by a chronic, pruritic eruption of small papules or

cysts formed by keratin-plugged apocrine glands. It is commonly present over the

lower abdomen, mons pubis, labia majora, and inner portions of the thighs.

Hidradenitis suppurativa is a chronic condition involving the apocrine

glands with the formation of multiple deep nodules, scars, pits, and sinuses

that occur in the axilla, vulva, and perineum. Hyperpigmentation and

secondary infection are often seen. Hidradenitis suppurativa can be extremely

painful and debilitating. It has been treated with antibiotics, isotretinoin, or

steroids; surgical therapy with wide local excision may be necessary (94).

Acanthosis Nigricans

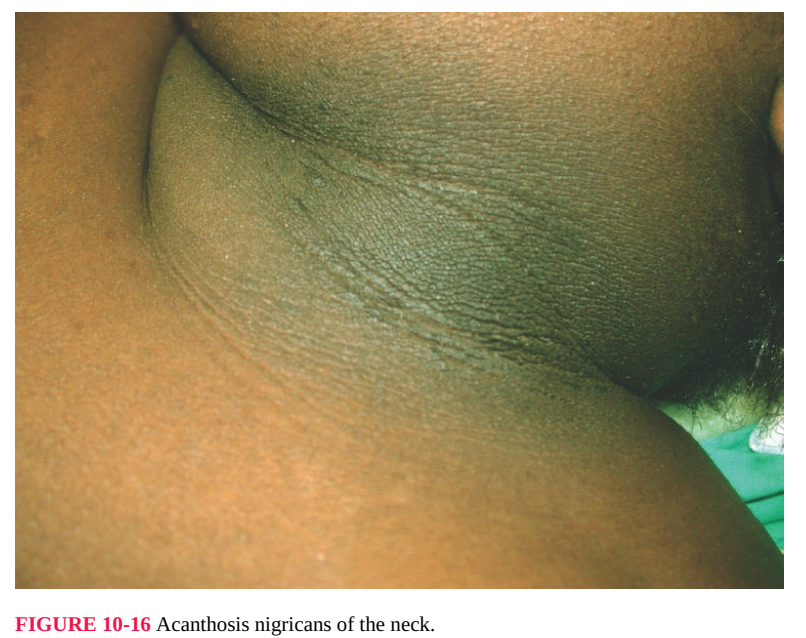

This disease involves widespread velvety pigmentation in skin folds, particularly

the axillae, neck, thighs, submammary area, and vulva and surrounding skin (Fig.

10-16). It is of particular interest to gynecologists because of its association with

hyperandrogenism and PCOS; as such, it is associated with obesity, chronic

anovulation, acne, glucose intolerance, insulin resistance, and cardiovascular

disease (95). Topical and oral retinoids are used to treat the acanthosis nigricans,

along with management of the underlying conditions including obesity and

insulin resistance or diabetes.

FIGURE 10-16 Acanthosis nigricans of the neck.

Extramammary Paget Disease

This is an intraepithelial neoplasia containing vacuolated Paget cells (see Chapter

16). Clinically, the appearance of Paget disease is variable, and it may have an

appearance varying from moist, oozing ulcerations to an eczematoid lesion with

scaling and crusting to a grayish lesion (96). It may be confused with candidiasis,

psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, and VIN. A biopsy to confirm

the diagnosis is mandatory. Treatment has traditionally been surgery, although

recurrences are very common; topical therapies including imiquimod are being

used (97).

Vulvar Intraepithelial Neoplasia

VIN is associated with HPV infection and is increasing in frequency,

particularly among young women (see Chapter 16). Diagnosis requires biopsy

of any suspicious vulvar lesions, particularly those that are pigmented or

discolored. The increasing frequency of this entity dictates a careful vulvar

inspection during annual gynecologic examinations.

508Vulvar Tumors, Cysts, and Masses

Condylomata Acuminata

These are very common vulvar lesions and are usually easily recognized.

They may resolve spontaneously; treatment is guided by wart number, size,

and anatomic site; patient preference; cost of treatment; convenience;

adverse effects; and provider experience (98). Treatments may be patientapplied or provider-administered. Other sexually transmitted organisms,

such as the virus responsible for M. contagiosum and the lesions of syphilis

and condylomata lata, may occasionally be mistaken for vulvar condylomata

acuminata caused by HPV (see Chapter 15). A summary of benign vulvar

tumors is listed in Table 10-12. There is an argument regarding whether

sebaceous cysts exist on the vulva or whether these lesions are histopathologically

epidermal or epidermal inclusion cysts (99). The so-called sebaceous cysts are

clinically indistinguishable from epidermal inclusion cysts that may result from

the burial of fragments of skin after the trauma of childbirth or episiotomy or that

arise from occluded pilosebaceous ducts. These cysts are seldom symptomatic,

although if infection develops, incision and drainage may be required acutely, and

ultimately complete excision is indicated.

Table 10-12 Types of Vulvar Tumors

1. Cystic lesions

Bartholin duct cyst

Cyst in the canal of Nuck (hydrocele)

Epithelial inclusion cyst

Skene duct cyst

2. Solid tumors

Acrochordon (skin tag)

Angiokeratoma

Bartholin gland adenoma

Cherry angioma

Fibroma

509Hemangioma

Hidradenoma

Lipoma

Granular cell myoblastoma

Neurofibroma

Papillomatosis

3. Anatomic

Hernia

Urethral diverticulum

Varicosities

4. Infections

Abscess—Bartholin, Skene, periclitoral, other

Condyloma lata

Molluscum contagiosum

Pyogenic granuloma

5. Ectopic

Endometriosis

Ectopic breast tissue

Bartholin Duct Cysts

These are common vulvar lesions in reproductive age women. They result from

occlusion of the duct with accumulation of mucus and may be asymptomatic.

Infection of the gland can result in the accumulation of purulent material, with the

formation of a rapidly enlarging, painful, inflammatory mass (a Bartholin

abscess). An inflatable bulb-tipped catheter was described by Word and is quite

easy to use (100). The small catheter is inserted through a small stab wound into

the abscess after infiltration of the skin with local anesthesia; the balloon of the

catheter is inflated with 2 to 3 mL of saline and the catheter remains in place for 4

to 6 weeks, allowing epithelialization of a tract and the creation of a permanent

510gland opening.

Skene Duct Cysts

These are cystic dilations of the Skene glands, typically located adjacent to the

urethral meatus within the vulvar vestibule. Although most are small and often

asymptomatic, they may enlarge and cause urinary obstruction, requiring excision

(Fig. 10-17).

FIGURE 10-17 The Skene gland cyst.

Painful Intercourse

Painful intercourse (dyspareunia) may be caused by many different vulvovaginal

conditions, including common vaginal infections and vaginismus (see Chapters

15 and 17). A careful sexual history is essential, as is a careful examination of the

vulvar area and vagina. Vulvodynia is the term used to describe unexplained

vulvar pain, sexual dysfunction, and the resultant psychological disability

(101,102). The term vulvar vestibulitis was previously used to describe a

situation in which there is pain during intercourse or when attempting to

511insert an object into the vagina; pain on pressure to the vestibule on

examination and vestibular erythema (known as the Friedrich triad); this

entity is now described as localized vulvodynia, which may be provoked or

spontaneous, primary or secondary, and intermittent, persistent, constant,

immediate, or delayed (see Chapter 12) (102,103). A number of studies failed to

demonstrate a consistent relationship with any genital infectious organism,

including C. trachomatis, gonorrhea, Trichomonas, mycoplasma, Ureaplasma,

Gardnerella, candida, or HPV, and the condition has been characterized as

multifactorial, with inflammatory, neuropathic, and functional components (104).

Although the symptoms of dyspareunia with insertion can be disabling, no

curative therapies were found. Medical and behavioral therapies are of some

benefit, and some authors encourage surgery, but the role of this treatment and

newer therapies such as the injection of botulinum toxin A is not well established

(104).

Vulvar Ulcers

A number of STDs can cause vulvar ulcers, including herpes simplex virus,

syphilis, lymphogranuloma venereum, and granuloma inguinale (see Chapter 15).

Crohn disease can include vulvar involvement with abscesses, fistulae, sinus

tracts, fenestrations, and other scarring. Medical treatment with systemic steroids

and other systemic agents is the standard therapy; surgical therapy for intestinal

and vulvar disease may be required.

The Behçet Disease

This systemic condition is characterized by genital and oral ulcerations with

ocular inflammation and many other manifestations (105). The cause and the

most effective therapy are not well established, although anti-inflammatory,

immunomodular, and immunosuppressive therapies may be effective (106).

Lichen Planus

This condition causes oral and genital ulcerations. Typically, there is

desquamative vaginitis with erosion of the vestibule. Treatment is based on the

use of topical and systemic steroids. Plasma cell mucositis appears as erosions in

the vulvar area, particularly the vestibule. Biopsy is essential in establishing the

diagnosis.

Vaginal Conditions