Endometriosis

BS. Nguyễn Hồng Anh

KEY POINTS

1 Endometriosis is diagnosed by visualization of lesions during laparoscopy, ideally with histologic confirmation; positive histology confirms the diagnosis, but negative histology does not exclude it.

2 Endometriosis can be associated with infertility, pelvic pain, that is, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia and nonmenstrual pain, and reduced quality of life.

3 Severe or deep endometriosis should be managed in a facility with the necessary expertise to provide treatment in a multidisciplinary context, including advanced laparoscopic surgery and laparotomy.

4 The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) staging system for endometriosis is subjective and correlates poorly with pelvic pain and infertility.

5 The Endometriosis Fertility Index (EFI) predicts non-in vitro fertilization (IVF) pregnancy rates after surgical treatment of endometriosis.

6 Suppression of ovarian function reduces pain associated with endometriosis. Different classes of hormonal drugs—combination oral contraceptives, progestins, gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists—are equally effective in reducing pain but have differing side effects and costs.

7 Ablation or resection of endometriotic lesions plus adhesiolysis in minimal to mild endometriosis is more effective than diagnostic laparoscopy alone in improving fertility.

8 Suppression of ovarian function is not effective in improving subsequent fertility in patients with endometriosis.

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial-like tissue (glands and/or stroma) outside the uterus. The most frequent sites of implantation are the pelvic viscera and the peritoneum but, although rare, it can also be found in the pericardium, pleura, lung, and even the brain. Endometriosis varies in appearance from a few minimal lesions on otherwise intact pelvic organs, to deep infiltrating nodules and massive ovarian endometriotic cysts with extensive adhesions involving bowel, bladder, and ureter resulting in significant distortion of the pelvic anatomy. It is estimated to occur in 10% of reproductiveage women and is associated with pelvic pain and infertility. Considerable progress in understanding the pathogenesis, spontaneous evolution, diagnosis, and treatment of endometriosis has occurred. The European Society for Human

Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) guidelines for the clinical management of endometriosis are published and regularly updated to present emerging clinical evidence (1).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Prevalence

Endometriosis is found predominantly in women of reproductive age but is reported in adolescents and in postmenopausal women receiving hormonal replacement therapy (2). It is found in women of all ethnic and social groups.

Estimates of the frequency of endometriosis vary widely, but the prevalence of the condition is assumed to be around 10% women of reproductive age (3,4). Although no consistent information is available on the incidence of the disease, temporal trends suggest an increase among women of reproductive age (4). The World Endometriosis Research Foundation (WERF) EndoCost study calculated the costs of women with histologically proven endometriosis treated in referral centers (5). The study showed that the costs to women with endometriosis are substantial, resulting in an economic burden similar to the estimated annual health care costs for diabetes mellitus, Crohn disease, and rheumatoid arthritis (5).

In women with pelvic pain or infertility, a high prevalence of endometriosis (from a low of 20% to a high of 90%) is reported (6,7). In women with unexplained infertility (regular menstrual cycle, normal pelvic imaging, normospermic partner) with or without pain, the prevalence of endometriosis is reported to be as high as 50% (8). In asymptomatic women undergoing tubal ligation (women of proven fertility), the prevalence of endometriosis ranges from 3% to 43% (9–14). This variation in the reported prevalence may be explained by several factors.

First, it may vary with the diagnostic method used: laparoscopy, the operation of choice for diagnosis, is a better method than laparotomy for diagnosing minimal to mild endometriosis.

Second, minimal or mild endometriosis may be more thoroughly evaluated in asymptomatic patients than in asymptomatic patients during tubal sterilization.

Third, the interest and experience of the surgeon has relevance because there is a wide variation in the appearance of subtle endometriosis implants, cysts, and adhesions. Most studies that evaluate the prevalence of endometriosis in women of reproductive age lack histologic confirmation (9–11,15–20).

Risk and Protective Factors

The following are possible risk factors for endometriosis: infertility, red hair, early age at menarche, shorter menstrual cycle length, hypermenorrhea, nulliparity, müllerian anomalies, low birth weight (less than 7 pounds), being one of multiple fetal gestation, diethylstilbestrol (DES) exposure, endometriosis in first-degree relative, tall height, dioxin or polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB) exposure, a diet high in fat and red meat, and prior surgeries or medical therapy for endometriosis (21,22). Prior use of contraception or intrauterine device (IUD), or smoking is not associated with increased risk of endometriosis (23,24). Protective factors against the development of endometriosis include multiparity, lactation, tobacco exposure in utero, increased body mass index, increased waist-to-hip ratios, and diet high in vegetables and fruits (21,25). Some evidence suggests that women with a “pinpoint cervix” have an increased risk for endometriosis, but more studies are needed to confirm this observation (26).

Endometriosis and Cancer

Several publications link endometriosis with an increased risk for certain gynecologic and nongynecologic cancers (27,28). These associations are controversial and no good data exist to inform clinicians regarding the best management of patients who might be at risk of developing such cancers (1). Endometriosis should not be considered a medical condition associated with a clinically relevant risk of any specific cancer (29). Data from large cohort and case-control studies indicate an increased risk of ovarian cancers in women with endometriosis. The observed effect sizes are modest, varying between 1.3 and 1.9 (30). Evidence from clinical series consistently demonstrates that the association is confined to the endometrioid and clear-cell histologic types of ovarian cancer (31). A causal relationship between endometriosis and these specific histotypes of ovarian cancer should be recognized, but the low magnitude of the risk observed is consistent with the view that ectopic endometrium undergoes malignant transformation with a frequency similar to its eutopic counterpart (32). Evidence for an association with melanoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma has been reported but needs to be verified, whereas an increased risk for other gynecologic cancer types is not supported (31).

ETIOLOGY

Although signs and symptoms of endometriosis have been described since the 1800s, its widespread occurrence was acknowledged only during the 20th century. Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent disease. Three theories were proposed to explain the pathogenesis of endometriosis:

1. Ectopic transplantation of endometrial tissue

2. Coelomic metaplasia

The induction theory

No single theory can account for the location of endometriosis in all cases.

Transplantation Theory

The transplantation theory, originally proposed by Sampson in the mid- 1920s, is based on the assumption that endometriosis is caused by the seeding and implantation of endometrial cells by transtubal regurgitation during menstruation (33). Substantial clinical and experimental data support this hypothesis (6,34). Retrograde menstruation occurs in 70% to 90% of women, and it may be more common in women with endometriosis than in those without the disease (9,35). The presence of endometrial cells in the peritoneal fluid, indicating retrograde menstruation, is reported in 59% to 79% of women during menses or in the early follicular phase, and these cells can be cultured in vitro (36,37). The presence of endometrial cells in the dialysate of women undergoing peritoneal dialysis during menses supports the theory of retrograde menstruation (38).

Endometriosis is most often found in dependent portions of the pelvis—the ovaries, the anterior and posterior cul-de-sac, the uterosacral ligaments, the posterior uterus, and the posterior broad ligaments (39). The menstrual reflux theory combined with the clockwise peritoneal fluid current explains why endometriosis is predominantly located on the left side of the pelvis (refluxed endometrial cells implant more easily in the rectosigmoidal area) and why diaphragmatic endometriosis is found more frequently on the right side (refluxed endometrial cells implant there by the falciform ligament) (40,41).

Endometrium obtained during menses can grow when injected beneath abdominal skin or into the pelvic cavity of animals (42,43). Endometriosis was found in 50% of Rhesus monkeys after surgical transposition of the cervix to allow intra-abdominal menstruation (44). Increased retrograde menstruation by obstruction of the outflow of menstrual fluid from the uterus is associated with a higher incidence of endometriosis in women and in baboons (45–47). Women with shorter intervals between menstruation and longer duration of menses are more likely to have retrograde menstruation and are at higher risk for endometriosis (48). Menstruation is associated with intraperitoneal inflammation in women and baboons, but a limited quantity of endometrial cells can be identified in peritoneal fluid during menstruation in women, possibly because endometrial–peritoneal attachment is reported to occur within 24 hours (49–51).

Ovarian endometriosis may be caused by either retrograde menstruation or by lymphatic flow from the uterus to the ovary; metaplasia and bleeding from a corpus luteum may be a critical event in the development of some endometriomas (52–54).

Deep endometriosis, with a depth of at least 5 mm beneath the peritoneum, can present as nodules in the cul-de-sac, rectosigmoid, and bladder area and occurs with other forms of peritoneal or ovarian endometriosis (55).

According to anatomic, surgical, and pathologic findings, deep endometriotic lesions originate intraperitoneally rather than extraperitoneally. The lateral asymmetry in the occurrence of ureteral endometriosis is compatible with the menstrual reflux theory and with the anatomic differences of the left and right hemipelvis (40). Adolescents and young women can have peritoneal disease (56).

This observation, together with evidence from the development and spontaneous evolution of endometriosis in baboons, supports the notion that endometriosis starts as peritoneal disease and that the three different phenotypes and locations of endometriosis (peritoneal, ovarian, and deep) represent a homogeneous disease continuum with a single origin (i.e., regurgitated endometrium), rather than three different disease entities (40,57,58).

Extrapelvic endometriosis, although rare (1% to 2%), may result from vascular or lymphatic dissemination of endometrial cells to many gynecologic (vulva, vagina, cervix) and nongynecologic sites. The latter include bowel (appendix, colon, small intestine, hernia sacs), lungs and pleural cavity, skin (cesarean section, episiotomy or other surgical scars, inguinal region, extremities, umbilicus), lymph glands, nerves, and brain (59).

Coelomic Metaplasia

The transformation (metaplasia) of coelomic epithelium into endometrial tissue is a proposed mechanism for the origin of endometriosis. One study evaluating structural and cell surface antigen expression in the rete ovarii and epoophoron reported little commonality between endometriosis and ovarian surface epithelium, suggesting that serosal metaplasia is unlikely in the ovary (60). The results of another study involving the genetic induction of endometriosis in mice suggest that ovarian endometriotic lesions may arise directly from the ovarian surface epithelium through a metaplastic differentiation process induced by activation of an oncogenic K-ras allele (53).

Induction Theory

The induction theory is an extension of the coelomic metaplasia theory. It proposes that an endogenous (undefined) biochemical factor can induce undifferentiated peritoneal cells to develop into endometrial tissue. This theory is supported by experiments in rabbits but is not substantiated in women or nonhuman primates (61,62).

Genetic Factors

Endometriosis is a complex disorder caused by a combination of multiple genetic and environmental factors. These genetic factors need to be divided into germline and somatic genetic variants. The former is inherited and results in a higher chance of developing endometriosis, the latter are somatic alterations that possibly play a role in the pathophysiology of endometriosis.

Germline Variants

Inherited genetic variants associated with endometriosis confer a genetic susceptibility to develop the disease but represent only approximately 50% of the risk associated with the disease (63). The heritable component of endometriosis is demonstrated by familial clustering in humans and in Rhesus monkeys, a founder effect detected in the Icelandic population, higher concordance in monozygotic versus dizygotic twins, a similar age at onset of symptoms in affected nontwin sisters, an increased prevalence of endometriosis among first-degree relatives and a 15% prevalence of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings suggestive of endometriosis in the first-degree relatives of women with ASRM stage III or IV disease (64). The induction of human-like endometriosis in mice by genetic activation of an oncogenic K-ras allele lends further support to the genetic basis of this disorder (53).

The risk of endometriosis is seven times greater if a first-degree relative is affected by endometriosis (65). Because no specific mendelian inheritance pattern is identified, multifactorial inheritance is postulated. Family linkage studies and genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have provided insights on the genetic variants contributing to the hereditary risk of endometriosis. Family linkage studies identify genetic variants that lead to clustering of endometriosis in certain families, but these variants are often rare in the general population. GWAS studies uncover common genetic variants in the general population related to an increased risk of endometriosis (63).

A meta-analysis of 11 GWAS identified 19 independent single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with endometriosis (66). However, all these polymorphisms combined explain only approximately 5% of variance in endometriosis. These genetic variants are located in or near a wide variety of genes with functions in diverse pathways: sex steroid hormone signaling (FSHB, ESR1), inflammation (NFE2L3), oncogenesis (ID4), uterine development (HOXA10, HOXA11), WNT signaling (WNT4, MIR148), estrogen responsive genes (GREB1, KDR) and genes involved in the actin cytoskeleton or cellular adhesion (FN1, VEZT, ANRIL). Large genome-wide linkage studies, including more than 1,300 families with multiple women affected by endometriosis, have identified three linkage regions of endometriosis: on chromosome 10q26, chromosome 20p13, and chromosome 7p13-15 (63,67,68). The genes in these linkage regions have roles in estrogen metabolism (CYP2C19 in the 10q26 region) and in endometrial or uterine development (INHBA, SFRP4 and HOXA10 in the 7p13-15 region).

Functional studies of the genes in these endometriosis risk loci are needed to elucidate their precise role and determine the effects of the variants in underlying pathways. These targeted functional gene studies have the potential to provide us with important new insights on the pathogenesis of endometriosis.

Somatic Alterations

Aneuploidy

Epithelial cells of endometriotic cysts are monoclonal on the basis of phosphoglycerate kinase gene methylation, and normal endometrial glands are monoclonal (69,70). In a comparison of endometriotic tissue with eutopic endometrium, flow cytometric DNA analysis failed to show aneuploidy (71).

Studies using comparative genomic hybridization, or multicolor in situ hybridization, showed aneuploidy for chromosomes 11, 16, and 17, increased heterogeneity of chromosome 17 aneuploidy, and losses of 1p and 22q (50%), 5p (33%), 6q (27%), 70 (22%), 9q (22%), and 16 (22%) of 18 selected endometriotic tissues (72–74). In another study, trisomies 1 and 7, and monosomies 9 and 17 were found in endometriosis, ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinoma, and normal endometrium (75). The proportions of aneusomic cells were significantly higher in ovarian endometriosis compared with extragonadal endometriosis and normal endometrium (p <0.001), suggesting a role of the ovarian stromal milieu in the induction of genetic changes, which may lead to invasive cancer in isolated cases (75).

Microsatellite DNA assays reveal an allelic imbalance (loss of heterozygosity) in p16 (Ink4), GALT, p53, and APOA2 loci in patients with endometriosis and in stage II of endometriosis (76). Another report found a loss of heterozygosity in 28% of endometriotic lesions at one or more sites: chromosomes 9p (18%), 11q (18%), and 22q (15%) (70).

Somatic Mutations

Somatic mutations in genes or chromosomes are, by definition, never passed on to progeny but can play an important role in pathogenesis of diseases such as cancer.

The role of somatic mutations in endometriosis is not well understood. Patients with clear cell ovarian carcinoma or endometrioid ovarian carcinoma often have concomitant endometriosis and endometriosis is well recognized as a risk factor for these types of ovarian cancer. Investigation of endometriosis lesions occurring synchronously with clear cell ovarian carcinoma or endometrioid ovarian carcinoma showed somatic mutations in ARID1A, PIK3CA, and in the MET oncogenes (77–79). However, data on the presence of somatic alterations in noncancer-associated endometriosis are very limited. One study revealed the presence of somatic mutations in noncancer-associated deep endometriotic lesions in 19 of 24 patients (79%) (80). Five patients harbored known cancer driver mutations in ARID1A, PIK3CA, KRAS, or PPP2R1A although deep infiltrating endometriosis has virtually no risk for malignant transformation. All the tested somatic mutations appeared to be confined to the epithelial compartment of endometriotic lesions.

Immunologic Factors and Inflammation

Retrograde menstruation appears to be a common event in women and not all women who have retrograde menstruation develop endometriosis. The immune system may be altered in women with endometriosis, and it is hypothesized that the disease may develop as a result of reduced immunologic clearance of viable endometrial cells from the pelvic cavity (81,82). Endometriosis can be caused by decreased clearance of peritoneal fluid endometrial cells resulting from reduced natural killer (NK) cell activity or decreased macrophage activity (83). Decreased cell-mediated cytotoxicity toward autologous endometrial cells is associated with endometriosis (83–87). These studies used techniques that have considerable variability in target cells and methods (88,89). Whether NK cell activity is lower in patients with endometriosis than in those without endometriosis is controversial. Some reports demonstrate reduced NK activity and others found no increase in NK activity in women with moderate to severe disease (85–87,90–95). There is great variability in NK cell activity among normal individuals that may be related to variables such as smoking, drug use, and exercise (88).

In contrast, endometriosis can be considered a condition of immunologic tolerance, as opposed to ectopic endometrium, which essentially is self-tissue (81). It can be questioned why viable endometrial cells in the peritoneal fluid would be a target for NK cells or macrophages. Autotransplantation of blood vessels, muscles, skin grafts, and other tissues is extremely successful (84–86).

There is no in vitro evidence that peritoneal fluid macrophages actually attack and perform phagocytosis of viable peritoneal fluid endometrial cells. High-dose immunosuppression can slightly increase the progression of spontaneous endometriosis in baboons (96). There is no clinical evidence that the prevalence of endometriosis is increased in immunosuppressed patients. The fact that women with kidney transplants, who undergo chronic immunosuppression and are not known to have increased infertility problems can be considered indirect evidence that these patients do not develop extensive endometriosis.

Substantial evidence suggests that endometriosis is associated with a state of subclinical peritoneal inflammation, marked by an increased peritoneal fluid volume, increased peritoneal fluid white blood cell concentration (especially macrophages with increased activation status), and increased inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and angiogenesis-promoting substances. It is reported in baboons that subclinical peritoneal inflammation occurs during menstruation and after intrapelvic injection of endometrium (94). A higher basal activation status of peritoneal macrophages in women with endometriosis may impair fertility by reducing sperm motility, increasing sperm phagocytosis, or interfering with fertilization, possibly by increased secretion of cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) (97–101). Tumor necrosis factor may facilitate the pelvic implantation of ectopic endometrium (100,101).

The adherence of human endometrial stromal cells to mesothelial cells in vitro is increased by the pretreatment of mesothelial cells with physiologic doses of TNF- α (102). Macrophages or other cells may promote the growth of endometrial cells by secretion of growth and angiogenetic factors such as epidermal growth factor (EGF), macrophage-derived growth factor (MDGF), fibronectin, and adhesion molecules such as integrins (102–108). After attachment of endometrial cells to the peritoneum, subsequent invasion and growth appear to be regulated by matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) and their tissue inhibitors (109,110).

There is increasing evidence that local inflammation and secretion of prostaglandins (PGs) is related to differences in endometrial aromatase activity between women with and without endometriosis. Expression of aromatase cytochrome P450 protein and mRNA is present in human endometriotic implants but not in normal endometrium, suggesting that ectopic endometrium produces estrogens, which may be involved in the tissue growth interacting with the estrogen receptor (111). Inactivation of 17β-estradiol is impaired in endometriotic tissues because of deficient expression of 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2, which is normally expressed in eutopic endometrium in response to progesterone (112). The inappropriate aromatase expression in endometriosis lesions can be stimulated by prostaglandin E2 (PGE2). This reaction leads to local production of E2, which stimulates PGE2 production, resulting in a positivefeedback system between local inflammation and estrogen-driven local growth of ectopic endometrium (113).

The subclinical pelvic inflammatory status associated with endometriosis is reflected in the systemic circulation. Increased concentrations of C-reactive protein, serum amyloid A (SAA), TNF-α, membrane cofactor protein-1, interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-8, and chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 1 (CCR1) are observed in peripheral blood samples of patients with endometriosis when compared with controls (114). This observation offers a basis for the development of noninvasive diagnostic tests.

Both hypothesis-driven research and system biology approaches using mRNA microarray and proteomic techniques studies show that eutopic endometrium is biologically different in women with endometriosis when compared to controls with respect to proliferation, apoptosis, angiogenesis, and inflammatory pathways (115–118). Several studies show a higher prevalence of nerve fibers and neurotrophic factors in the eutopic endometrium from women with endometriosis when compared to controls (49,119).

Environmental Factors and Dioxin

There is an increasing awareness of potential links between reproductive health, infertility, and environmental pollution. Attention was directed toward the potential role of dioxins in the pathogenesis of endometriosis, but the issue remains controversial. A meta-analysis concluded that there is insufficient evidence in women or in nonhuman primates that endometriosis is caused by dioxin exposure (120).

Human Data

A 1976 explosion of a factory in Seveso, Italy, resulted in the highest recorded levels of dioxin exposure in humans, but data are not published (121). The Seveso Women’s Health Study will correlate prospective individual data on exposure to dioxin with reproductive endpoints such as the incidence of endometriosis, infertility, and decreased sperm quality. One case-control study failed to show an association in the general population between endometriosis and exposure to PCB and chlorinated pesticides during adulthood. No differences in mean plasma concentrations of 14-PCB and 11-chlorinated pesticides were found between women with and those without endometriosis (122). In another study, increased exposure to dioxin-like compounds is associated with (moderate to severe) endometriosis in a case-control study in women (123). Genetic mechanisms may play a role in dioxin exposure and the development of endometriosis. Transcripts of the CYP1A1 gene, a dioxin-induced gene, are significantly higher (nine times higher) in endometriotic tissues than in eutopic endometrium (113). Other investigators report a similar expression of aryl hydrocarbon receptor and dioxinrelated genes (using semiquantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction) in the endometrium from women with or without endometriosis (124).

In Japanese women, no association was found between endometriosis prevalence or severity and polymorphisms for aryl hydrocarbon receptor repressor, aryl hydrocarbon (x2) receptor, and aryl hydrocarbon nuclear translocator or CYP1A1 genes (125). Based on these data, there is insufficient evidence supporting the association between endometriosis and dioxin exposure in humans.

Nonhuman Primates

An initial retrospective case-control study reported that the prevalence of endometriosis was not statistically different (p = 0.08) between monkeys chronically exposed to dioxin for 4 years (11 of 14, 79%) and unexposed animals (2 of 6, 33%) after a period of 10 years. A positive correlation was found between the severity of endometriosis and dioxin dose, serum levels of dioxin, and dioxinlike chemicals (126,127). Two prospective studies evaluated the association between dioxin exposure and development of endometriosis in Rhesus monkeys.

In one study, monkeys exposed for 12 months to low-dose dioxin (0.71 ng/kg/day) had endometriosis implants with smaller maximal and minimal diameters and similar survival rate when compared with endometriotic lesions in unexposed controls, suggesting no effect of dioxin on endometriosis (128). After 12 months of exposure to high-dose dioxin (17.86 ng/kg/day), larger diameters and a higher survival rate of endometriosis implants were observed in exposed

Rhesus monkeys compared with unexposed controls. The second randomized study performed in 80 Rhesus monkeys compared those with no treatment with those treated with 0, 5, 20, 40, and 80 μg of aroclor (1,254 kg/day) for 6 years. Endometriosis occurred in 37% of controls and in 25% of treated monkeys as determined by laparoscopy and necropsy data (129). No association was observed between endometriosis severity and PCB exposure. These data question the importance of dioxin exposure, except at high doses, in the development of endometriosis in primates.

Rodents

Continuous exposure to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-P-dioxin inhibited the growth of surgically induced endometriosis in ovariectomized mice treated with highdose estradiol. No correlation was observed between the dose of dioxin and survival of endometrial implants, adhesions, and serum E2 levels (130). In ovariectomized mice induced with endometriosis, similar stimulating effects of estrone and 4-chlorodiphenyl ether (4-CDE) were observed on survival rates of endometriotic mice, suggesting an estrogen-like effect of 4-CDE (131). Potential mechanisms mediating dioxin action to promote endometriosis in rodents are complex and probably different in rats and mice, and furthermore in women. The mouse appears to be a better model to elucidate these mechanisms, but both models have important limitations (132,133).

Stem Cells

In 2004 the first evidence for the presence of adult stem cells in endometrium was published (134). In one study, stem cells were identified in endometrium isolated from hysterectomy tissue. Concurrently, it was reported that some epithelial and stromal cells in human endometrium of bone marrow transplant recipients were of donor origin (135). In the next decade, a key role of adult stem cells in normal endometrial physiology was discovered (136).

Following the discovery of endometrial stem cells, it was proposed that these stem cells play a role in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. The first hypothesis is an extension of Sampson theory of retrograde menstruation: endometrial stem cells, with intrinsic abnormalities such as germline or somatic mutations, may have increased propensity to implant on the peritoneum after retrograde menstruation. Studies showed that women with endometriosis shed basalis endometrium at menstruation, increasing the likelihood of endometrial epithelial progenitor cells gaining access to the peritoneal cavity and stem cells have been identified in endometriotic lesions (136). However, the presence of endometrial stem/progenitor cells in peritoneal fluid has not yet been reported, which is crucial for identifying their role in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. A second hypothesis focuses on abnormal stem cell recruitment in patients with endometriosis (137). Stem cells from the bone marrow or alternate sources could be preferentially recruited in ectopic over eutopic endometrium through altered expression of chemotactic ligands such as CXCL12 (137). Abnormal endometrial function caused by impaired recruitment of stem cells to the eutopic endometrium could be a contributing endometrial factor to endometriosis-associated infertility (137).

Several studies have addressed the role of stem cells in endometriosis, but no strong direct evidence for the role of endometrial stem/progenitor cells in the pathogenesis of endometriosis has been reported.

Future Research

The study of endometriosis is compounded by the need to determine the presence or absence of pathology. The pathogenesis of endometriosis, the pathophysiology of related infertility, and the spontaneous evolution of endometriosis are being studied. At the time of diagnosis, most patients with endometriosis had the disease for an unknown period, making it difficult to initiate clinical experiments that would determine the etiology or progression of the disease (34). Because endometriosis occurs naturally only in women and nonhuman primates, and invasive experiments cannot be performed easily, it is difficult to undertake properly controlled studies.

There is a need for the development of good in vitro and in vivo models for endometriosis. The main advantage of the rodent models used to study endometriosis is their low cost relative to nonhuman primates, but the disadvantages are numerous (138–141). First of all, in these models, the type of lesion appears to be quite different from the variety of pigmented and nonpigmented lesions observed in women (138–140). Secondly, there is a lack of standardization in rodent endometriosis models and no consensus on relevant outcome measures. Nonhuman primates are phylogenetically close to humans, have a comparable menstrual cycle, are afflicted with spontaneous endometriosis, and when induced with endometriosis, develop macroscopic lesions that are similar to those found in human disease (44,142–146). Spontaneous endometriosis in the baboon is minimal and disseminated, similar to the different stages of endometriosis in women (142,147–149).

The techniques for in vitro experiments have significantly improved, including the development of endometrial organoids (150,151). Application of these promising new techniques on endometriotic tissue and further improvement of in vitro models for endometriosis hold great potential for future research.

DIAGNOSIS

Clinical Presentation

[2] Endometriosis should be suspected in women with infertility, dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, or chronic pelvic pain, although these symptoms can be associated with other diseases. Endometriosis may be asymptomatic, even in women with more advanced disease (i.e., ovarian endometriosis or deep endometriosis).

Endometriosis can be associated with significant gastrointestinal symptoms (pain, nausea, vomiting, early satiety, bloating and distention, altered bowel habits). A characteristic motility change (ampulla of Vater– duodenal spasm, a seizure equivalent of the enteric nervous system, along with bacterial overgrowth) is documented in most women with the disease (152).

Women of reproductive age with endometriosis are not osteopenic (153). The average delay between onset of pain symptoms and surgically confirmed endometriosis is quite long: 8 years or longer in the United

Kingdom and 9 to 12 years in the United States (154). Similar durations were observed in Scandinavia and in Brazil (155,156). A delay in diagnosis of endometriosis of 6 and 3 years in women with pain and women with infertility, respectively, was reported. Over previous decades, there was a steady decrease in the delay in diagnosis and a decline in the prevalence of advanced endometriosis at first diagnosis (157). Patient awareness of endometriosis was increased. Many patients’ quality of life is affected by pain, emotional impact of infertility, anger about disease recurrence, and uncertainty about the future regarding repeated surgeries or long-term medical therapy and its side effects (158). Endometriosis should be perceived as a chronic disease, at least in a subset of highly symptomatic women, and quality-of-life should be evaluated using reliable and validated questionnaires (159).

Pain

[3] In adult women, dysmenorrhea may be especially suggestive of endometriosis if it begins after years of pain-free menses. Dysmenorrhea often starts before the onset of menstrual bleeding and continues throughout the menstrual period. In adolescents, the pain may be present after menarche without an interval of pain-free menses. Evidence suggests that absenteeism from school and the incidence and duration of oral contraceptive (OC) use for severe primary dysmenorrhea during adolescence is higher in women who later develop deep endometriosis than in women without deep endometriosis (160).

The distribution of pain is variable but most often is bilateral. Local symptoms can arise from rectal, ureteral, and bladder involvement, and lower back pain can occur. Some women with extensive disease have no pain, whereas others with only minimal to mild disease may experience severe pelvic pain. All endometriosis lesion types are associated with pelvic pain, including minimal to mild endometriosis (161). Endometriomas are not associated with dysmenorrheal severity, and dysmenorrhea is less frequent in women with only ovarian endometriomas compared with other locations (162,163). Endometriomas can be considered a marker for greater severity of deep lesions (164). Deep lesions are consistently associated with pelvic pain, gastrointestinal symptoms, and painful defecation (165). The role of adhesions in pain and endometriosis is poorly understood (166).

Many studies failed to detect a correlation between the degree of pelvic pain and the severity of endometriosis (12,163,167). Some studies reported a positive correlation between endometriosis stage and endometriosis-related dysmenorrhea or chronic pelvic pain (168,169). In one study, a significant but weak correlation was observed between endometriosis stage and severity of dysmenorrhea and nonmenstrual pain, whereas a strong association was found between posterior cul-de-sac lesions and dyspareunia (170).

Possible mechanisms causing pain in patients with endometriosis include local peritoneal inflammation, deep infiltration with tissue damage, adhesion formation, fibrotic thickening, and collection of shed menstrual blood in endometriotic implants, resulting in painful traction with the physiologic movement of tissues (171,172). The character of pelvic pain is related to the anatomic location of deep endometriotic lesions (165). Severe pelvic pain and dyspareunia may be associated with deep endometriosis (7,171,173). In rectovaginal endometriotic nodules, a close histologic relationship was observed between nerves and endometriotic foci and between nerves and the fibrotic component of the nodule (174). Increasing evidence suggests a close relationship between the density of innervation of endometriotic lesions and pain symptoms (170).

Infertility

Many arguments support the hypothesis that there is a causal relationship between the presence of endometriosis and infertility (175). The following factors have been reported:

1. Increased prevalence of endometriosis in infertile women (33%) when compared to women of proven fertility (4%), a reduced monthly fecundity rate (MFR) in baboons with mild to severe (spontaneous or induced) endometriosis when compared to those with minimal endometriosis or a normal pelvis.

2. Trend toward a reduced MFR in infertile women with minimal to mild endometriosis when compared to women with unexplained infertility.

3. Endometriotic ovarian cysts that negatively affect the rate of spontaneous ovulation (176).

4. Dose–effect relationship: A negative correlation between the r-AFS stage of endometriosis and the MFR and cumulative pregnancy rate (175,177).

5. Reduced MFR and cumulative pregnancy rate after donor sperm insemination in women with minimal to mild endometriosis when compared to those with a normal pelvis.

6. Reduced MFR after husband sperm insemination in women with minimal to mild endometriosis when compared to those with a normal pelvis.

7. Reduced implantation rate per embryo after in vitro fertilization (IVF) in women with endometriosis when compared to women with tubal factor infertility (175,178).

8. Increased MFR and cumulative pregnancy rate after surgical removal of minimal to mild endometriosis.

When endometriosis is moderate or severe, involving the ovaries and causing adhesions that block tubo-ovarian motility and ovum pickup, it is associated with infertility (176,179). This effect was shown in primates, including cynomolgus monkeys and baboons (145,180). Numerous mechanisms (ovulatory dysfunction, luteal insufficiency, luteinized unruptured follicle syndrome, recurrent abortion, altered immunity, and intraperitoneal inflammation) are proposed as explanations, but an association between fertility and minimal or mild endometriosis remains controversial (181).

Spontaneous Abortion

A possible association between endometriosis and spontaneous abortion was suggested in uncontrolled or retrospective studies. Some controlled studies evaluating the association between endometriosis and spontaneous abortion have important methodologic shortcomings: heterogeneity between cases and controls, analysis of the abortion rate before the diagnosis of endometriosis, and selection bias of study and control groups (81,182,183). Based on controlled prospective studies, there is no evidence that endometriosis is associated with (recurrent) pregnancy loss or that medical or surgical treatment of endometriosis reduces the spontaneous abortion rate (184–186). Some data suggest that miscarriage rates may be increased after treatment with assisted reproductive technology (187).

Endocrinologic Abnormalities

Endometriosis is associated with anovulation, abnormal follicular development with impaired follicle growth, reduced circulating E2 levels during the preovulatory phase, disturbed luteinizing hormone (LH) surge patterns, premenstrual spotting, luteinized unruptured follicle syndrome, and galactorrhea, and hyperprolactinemia (188). Increased incidence and recurrence of the luteinized unruptured follicle syndrome is reported in baboons with mild endometriosis, but not in primates with minimal endometriosis or a normal pelvis (189). Luteal insufficiency with reduced circulating E2 and progesterone levels, out-of-phase endometrial biopsies, and aberrant integrin expression was reported in the endometrium of women with endometriosis by some researchers, but these findings were not confirmed by other investigators (188,190,191). No convincing data exist to conclude that the incidence of these endocrine abnormalities is increased in women who have endometriosis.

Extrapelvic Endometriosis

Extrapelvic endometriosis, although often asymptomatic, should be suspected when symptoms of pain or a palpable mass occur outside the pelvis in a cyclic pattern. Endometriosis involving the intestinal tract (especially colon) is the most common site of extrapelvic disease and may cause abdominal and back pain, abdominal distention, cyclic rectal bleeding, constipation, and obstruction. Ureteral involvement can lead to obstruction and result in cyclic pain, dysuria, and hematuria. Endometriosis lesions on the diaphragm often result in cyclic shoulder pain. Pulmonary endometriosis can manifest as pneumothorax, hemothorax, or hemoptysis during menses. Umbilical endometriosis should be suspected when a patient has a palpable mass and cyclic pain in the umbilical area (59).

Clinical Examination

In many women with endometriosis, no abnormality is detected during the clinical examination. However, the vulva, vagina, and cervix should be inspected for any signs of endometriosis, although the occurrence of endometriosis in these areas is rare (e.g., episiotomy scar). The presence of a narrow pinpoint cervical ostium can be a risk factor for endometriosis (26). Other signs of possible endometriosis include uterosacral or cul-de-sac nodularity, lateral or cervical displacement caused by uterosacral scarring, painful swelling of the rectovaginal septum, and unilateral ovarian cystic enlargement (192). In more advanced disease, the uterus is often in fixed retroversion, and the mobility of the ovaries and fallopian tubes is reduced (“frozen pelvis”). Evidence of deep endometriosis (deeper than 5 mm under the peritoneum) in the rectovaginal septum with cul-de-sac obliteration or cystic ovarian endometriosis should be suspected when there is clinical documentation of uterosacral nodularities during menses (193–195). In these cases, black-blue– colored lesions can sometimes be observed in the vagina during speculum examination.

Imaging

Based on the symptoms at presentation and the clinical examination the diagnosis of endometriosis can be suspected. However, endometriosis symptoms are not specific and the clinical examination may have false-negative results. The next step in the diagnostic workup is medical imaging. However, no imaging modality detects endometriosis accurately enough to replace surgical visual detection and biopsy for diagnosis and thus the gold standard for diagnosis of endometriosis remains laparoscopic visualization of lesions with histologic confirmation (196).

Ultrasound

The guidelines from the European Society of Human reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecology (ACOG) recommend transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) as a first imaging step in the diagnostic work up of women with suspected endometriosis. However, the sensitivity and specificity of TVUS for diagnosis of endometriosis are strongly dependent on the interest and experience of the sonographer and on the quality of the ultrasound equipment.

In a systematic review the accuracy of TVUS for detecting the different phenotypes of endometriosis (peritoneal, endometrioma, deep infiltrating) was assessed (196). TVUS could not reliably visualize peritoneal endometriosis (sensitivity = 65%, specificity = 95%). Compared to laparoscopy, TVUS has no value in diagnosing peritoneal endometriosis. However, TVUS is reliable in detecting or excluding the presence of an endometrioma (sensitivity = 93%, specificity = 96%). The typical ultrasound features of an endometriotic ovarian cyst in premenopausal women were described as “ground-glass echogenicity of the cyst fluid, one to four locules and no solid parts” (197). Studies evaluating the accuracy of TVUS for diagnosis of deep endometriosis mainly focus on rectovaginal or bladder nodules. TVUS can detect these deep endometriotic lesions with moderate reliability (sensitivity = 79%, specificity = 94%). The role of TVUS in diagnosis of deep endometriosis in more distant locations is limited.

In summary, the main role of TVUS in the diagnostic workup of endometriosis is detecting the presence of an endometrioma or deep endometriotic nodule

because it establishes the diagnosis with high certainty. Moreover, an

endometrioma or a deep nodule are very rarely isolated findings. Patients

with an endometrioma or a deep nodule often have other endometriotic lesions

and adhesions. Identification of an endometrioma or a deep nodule on TVUS

should always be followed by a detailed investigation for other (peritoneal and

deep) endometriotic lesions.

Local guidelines for the management of suspected ovarian malignancy should be followed in cases of ovarian endometrioma (1). Ultrasound scanning with or

without serum CA125 testing is usually used to identify rare instances of ovarian

cancer; however, CA125 levels are frequently elevated in the presence of

endometriomas (1).

The absence of endometriosis on TVUS does not rule out the presence of peritoneal or deep endometriosis. Based on the patients’ symptoms and

clinical examination further investigation and a diagnostic laparoscopy

should be considered.

Other Imaging Techniques

Other imaging techniques, including computed tomography (CT) and MRI, can be used to provide additional and confirmatory information, but they are not considered first line imaging modalities because of the high costs and their added value is unclear (1). Moreover, CT results in an important radiation dose, which should be avoided as much as possible in a population of young reproductive women.

MRI has a good sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of deep endometriosis and endometriomas, but the value in addition to TVUS is limited. A growing number of studies suggest that MRI has a role in the diagnosis of endometriosis because of a greater ability to detect small lesions and lesions on distant locations (extrapelvic endometriosis) (196). However, a negative MRI does not rule out peritoneal endometriosis because lesions are identified only if they are hemorrhagic, greater than 5 mm or when associated with extensive adhesions distorting the normal anatomy. Hysterosalpingography is not recommended as a diagnostic test for endometriosis, although the presence of filling defects (presence of hypertrophic or polypoid endometrium) has a significant positive correlation with endometriosis (positive and negative predictive values of 84% and 75%, respectively) (198).

Assessment of Intestinal and Urologic Involvement

Medical imaging plays an important role in establishing the diagnosis of endometriosis and imaging-based mapping of the extent of endometriosis is indispensable for appropriate planning of surgical management. If there is clinical evidence of deep endometriosis, ureteral, bladder, and bowel involvement should be assessed. Ureteral involvement may be asymptomatic in up to 50% of patients with deep endometriosis (199). Consideration should be given to performing ultrasound (transrectal, transvaginal, or renal), a CT urogram, or an MRI. A barium enema study might be useful, depending on the individual circumstances, to map the extent of disease present, which may be multifocal (1). There is no proof that one technique is superior to another; it is recommended that the technique that is most familiar to the radiologist involved be used.

Blood and Other Tests

There is no specific blood test for the diagnosis of endometriosis. A general endometriosis screening test may be neither appropriate (risk for overdiagnosis)

nor feasible. A blood test with a high sensitivity would be useful if that would

identify women with symptomatic endometriosis (pelvic pain, infertility) that is

not detectable by ultrasound imaging (200). This would include all cases of

minimal to mild endometriosis and those cases of moderate to severe

endometriosis without detectable ovarian endometriotic cysts or nodules (201).

These are patients who could benefit from laparoscopic surgery to reduce

endometriosis-associated pain and infertility or to diagnose and treat other pelvic

causes of pelvic pain or infertility, like pelvic adhesions. From that perspective, a

lower specificity would be acceptable because the main goal of such a test would

be to rule in all women with potential endometriosis or other pelvic diseases who

might benefit from surgery (202).

CA125

Levels of CA125, a glycoprotein from coelomic epithelium and common to most nonmucinous epithelial ovarian carcinomas, are significantly higher in

women with moderate or severe endometriosis and normal in women with

minimal or mild disease (203,204). It is presumed that endometriosis lesions

produce peritoneal irritation and inflammation and this leads to an increased

shedding of CA125 (204). During menstruation, an increase in CA125 levels was

shown in women with and without endometriosis (205–209). Other studies did

not find an increase during menses, or found an increase only with moderate to

severe endometriosis (210–213). The levels of CA125 vary widely: in patients

without endometriosis (8 to 22 U/mL in the nonmenstrual phase), in those with

minimal to mild endometriosis (14 to 31 U/mL in the nonmenstrual phase), and in

those with moderate to severe disease (13 to 95 U/mL in the nonmenstrual phase).

Compared with laparoscopy, measurement of serum CA125 levels has no

value as a diagnostic tool (214).

Laparoscopy

General Considerations

Unless disease is visible in the vagina or elsewhere, laparoscopy is the standard technique for visual inspection of the pelvis and establishment of a

definitive diagnosis (1). There is insufficient evidence to justify timing the

laparoscopy at a specific time in the menstrual cycle. Laparoscopic recognition of

endometriosis will vary with the experience of the surgeon, especially for subtle

bowel, bladder, ureteral, and diaphragmatic lesions (1). A meta-analysis of its

value against a histologic diagnosis showed (assuming a 10% pretest probability

of endometriosis) that a positive laparoscopy increases the likelihood of disease to

32% (95% confidence interval [CI], 21–46) and a negative laparoscopy decreases

the likelihood to 0.7% (95% CI, 0.1–5.0) (1,215). Diagnostic laparoscopy is

associated with an approximately 3% risk of minor complications (e.g., nausea,

shoulder tip pain) and a risk of major complications (e.g., bowel perforation,

vascular damage) of 0.6 to 1.8 per 1,000 cases (1,216,217). Endometriosis can be

treated during laparoscopy, thus combining diagnosis and therapy.

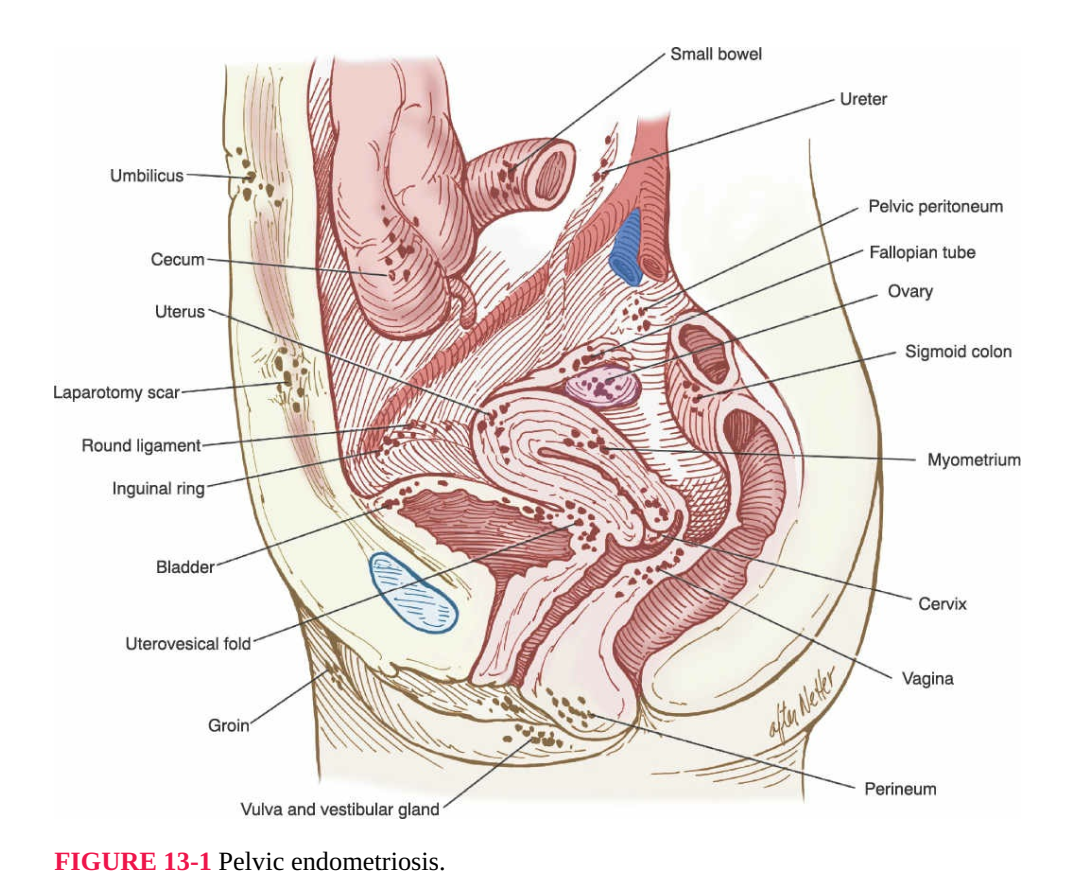

Laparoscopic Technique

During diagnostic laparoscopy, the pelvic and abdominal cavity should be systematically investigated for the presence of endometriosis. This

examination should include a complete inspection and palpation with a blunt

probe to check for nodularity as a sign of deep endometriosis of the bowel,

bladder, uterus, tubes, ovaries, cul-de-sac, or broad ligament (Fig. 13-1). The

type, location, and extent of all lesions and adhesions should be documented in

the operative notes; ideally, the findings should be recorded with photographs or on video (1).

Laparoscopic Findings

The laparoscopic findings of endometriosis include peritoneal lesions, ovarian

endometriotic cysts, and deep endometriosis invading the peritoneal surface with

a depth of at least 5 mm. Most patients with ovarian endometriotic cysts or

deep endometriosis also have peritoneal disease.

Peritoneal Endometriosis

Characteristic findings include typical (“powder-burn” or “gunshot”) lesions

on the serosal surfaces of the peritoneum. These lesions are black, dark

brown, or bluish nodules or small cysts containing old hemorrhage

surrounded by a variable degree of fibrosis (Fig. 13-2). Endometriosis can

appear as subtle lesions, including red implants (petechial, vesicular, polypoid,

hemorrhagic, red flame-like), serous or clear vesicles, white plaques or scarring,

yellow-brown discoloration of the peritoneum, and subovarian adhesions (Fig.

13-3) (139,140,142,218,219). Histologic confirmation of the laparoscopic

impression is essential for the diagnosis of endometriosis, for subtle lesions, and

for the typical lesions reported to be histologically negative in 24% of cases

(220,221).

Deep Endometriosis

Mild forms of deep endometriosis may be detected only by palpation under an

endometriotic lesion or by discovery of a palpable mass beneath visually normal

peritoneum, most notably in the posterior cul-de-sac (Fig. 13-4) (194). At

laparoscopy, deep endometriosis may have the appearance of minimal

disease, resulting in an underestimation of disease severity (194). Reduced

size of the cul-de-sac in women with deep endometriosis suggests that such

lesions develop not in the rectovaginal septum but intraperitoneally and that burial

of anterior rectal wall adhesions creates a false bottom, giving an erroneous

impression of extraperitoneal origin (222).

FIGURE 13-1 Pelvic endometriosis.

Ovarian Endometriosis

The diagnosis of ovarian endometriosis is facilitated by careful inspection of

all sides of both ovaries, which may be difficult when adhesions are present

in more advanced stages of disease (Fig. 13-5). With superficial ovarian

endometriosis, lesions can be both typical and subtle. Larger ovarian

endometriotic cysts (i.e., endometriomas) usually are located on the anterior

surface of the ovary and are associated with retraction, pigmentation, and

adhesions to the posterior peritoneum. These ovarian endometriotic cysts often

contain a thick, viscous dark brown fluid (i.e., “chocolate fluid”), composed

of hemosiderin derived from previous intraovarian hemorrhage. Because this

fluid may be found in other conditions, such as in hemorrhagic corpus luteum

cysts or neoplastic cysts, biopsy and preferably removal of the ovarian cyst for

histologic confirmation are necessary for the diagnosis in the revised

endometriosis classification of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM). If that is not possible, the presence of an ovarian endometriotic cyst

should be confirmed by the following features: cyst diameter of less than 12 cm,

adhesion to pelvic sidewall or broad ligament, endometriosis on the surface of the

ovary, and tarry, thick, chocolate-colored fluid content (223). Ovarian

endometriosis appears to be a marker for more extensive pelvic and intestinal

disease. Exclusive ovarian disease is found in only 1% of endometriosis patients,

with the remaining patients having extensive pelvic or intestinal endometriosis

(224).

Histologic Confirmation

[1] Positive histology confirms the diagnosis of endometriosis; negative histology does not exclude it (1). Whether histology should be obtained when peritoneal disease alone is present is controversial; visual inspection is usually adequate but histologic confirmation of at least one lesion is ideal (1).

In cases of ovarian endometrioma (>4 cm in diameter) and in deep endometriosis, histology is recommended to exclude rare instances of malignancy (1).

FIGURE 13-2 Typical and subtle endometriotic lesions on peritoneum. A: Typical blackpuckered lesions with hypervascularization and orange polypoid vesicles. B: Red polypoid lesions with hypervascularization. (Photographs from Dr. Christel Meuleman, Leuven University Fertility Center, Leuven University Hospitals, Leuven, Belgium.)

FIGURE 13-3 Ovarian endometriosis. A: Superficial ovarian endometriosis. B: Superficial ovarian endometriosis and endometrioma—laparoscopic image prior to adhesiolysis. C: Laparoscopic image of uterus and right ovary with dark endometrioma. D:

Ovarian endometriotic cystectomy. E: Ovarian endometriotic cystectomy. (Photographs from Dr. Christel Meuleman, Leuven University Fertility Center, Leuven University Hospitals, Leuven, Belgium.)

FIGURE 13-4 Laparoscopic excision of deep endometriosis from the cul-de-sac. A: Extensive endometriosis with deep nodule at the right uterosacral ligament, masked by adhesions. B: Deep nodule still present in dense adhesion between rectum and uterosacral ligaments. C: Cul-de-sac after resection of deep nodule with CO2 laser. (Photographs from Dr. Christel Meuleman, Leuven University Fertility Center, Leuven University Hospitals, Leuven, Belgium.)

FIGURE 13-5 Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine Classification. (From the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis. Am Soc Reprod Med 1997;5:817– 821.)

In a study of 44 patients with chronic pelvic pain, endometriosis was laparoscopically diagnosed in 36%, but histologic confirmation was obtained in

only 18%. This approach resulted in a low diagnostic accuracy of laparoscopic

inspection with a positive predictive value of only 45%, explained by a specificity

of only 77% (225).

Microscopically, endometriotic implants consist of endometrial glands

and/or stroma, with or without hemosiderin-laden macrophages (Fig. 13-6).

It is suggested that using these stringent and unvalidated histologic criteria may

result in significant underdiagnosis of endometriosis (6). Problems in obtaining

biopsies (especially small vesicles) and variability in tissue processing (step or

partial instead of serial sectioning) may contribute to false-negative results.

Endometrioid stroma may be more characteristic of endometriosis than

endometrioid glands (226). The presence of stromal endometriosis, which

contains endometrial stroma with hemosiderin-laden macrophages or hemorrhage,

was reported in women and in baboons and may represent a very early event in

the pathogenesis of endometriosis (148,220,221). Isolated endometrial stromal

cell nodules, immunohistochemically positive for vimentin and estrogen receptor,

can be found in the absence of endometrial glands along blood or lymphatic

vessels (227).

FIGURE 13-6 Histologic appearance of endometriosis: endometrial glandular epithelium, surrounded by stroma in typical lesion and clear vesicle.

Different types of lesions may have different degrees of proliferative or secretory glandular activity (226). Vascularization, mitotic activity, and the threedimensional structure of endometriosis lesions are key factors (171,228,229). Deep endometriosis is described as a specific type of pelvic endometriosis characterized by proliferative strands of glands and stroma in dense fibrous and smooth muscle tissue (20). Smooth muscles are frequent components of endometriotic lesions on the peritoneum, ovary, rectovaginal septum, and uterosacral ligaments (174).

Microscopic endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma in macroscopically normal pelvic peritoneum. It is important in the histogenesis of endometriosis and its recurrence after treatment (230,231). The clinical relevance of microscopic endometriosis is controversial

because it is not observed uniformly. Using undefined criteria for what constitutes

normal peritoneum, peritoneal biopsy specimens of 1 to 3 cm were obtained

during laparotomy from 20 patients with moderate to severe endometriosis (231).

Examination of the biopsy results with low-power scanning electron microscopy

revealed unsuspected microscopic endometriosis in 25% of cases not confirmed

by light microscopy. Peritoneal endometriotic foci were demonstrated by light

microscopy in areas that showed no obvious evidence of disease (232).

In serial sections of laparoscopic biopsies of normal peritoneum, 10% to

15% of women had microscopic endometriosis, and endometriosis was found

in 6% of those without macroscopic disease (219,233,234). Other studies were

unable to detect microscopic endometriosis in 2-mm biopsy specimens of visually

normal peritoneum (235–238). Examination of larger samples (5 to 15 mm) of

visually normal peritoneum revealed microscopic endometriosis in only 1 of 55

patients studied (239). A histologic study of serial sections through the entire

pelvic peritoneum of visually normal peritoneum from baboons with and without

disease indicated that microscopic endometriosis is a rare occurrence (96).

Macroscopically appearing normal peritoneum rarely contains microscopic

endometriosis (239).

Laparoscopic Classification

Endometriosis is a complex disease and at present there is no perfect staging system available. The most widely used staging system is the revised

American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification (rASRM). The

Endometriosis Fertility Index (EFI) has been shown to predict non-IVF pregnancy

rates for patients following surgical staging and treatment of endometriosis

(177,240). To supplement the rASRM classification with regard to the description

of deep endometriosis, the ENZIAN score was introduced (241–243). Although

the ENZIAN score appears to be a good complement to the rASRM score for

morphologic description of deep endometriosis and planning of surgery, it is not

widely used. Recently the World Endometriosis Society (WES) published a

consensus statement in which they recommend that all women undergoing

surgery should have the rASRM classification completed, women with deep

endometriosis should additionally have ENZIAN completed, and women for

whom future fertility is a concern should additionally have the EFI

completed (244).

American Society for Reproductive Medicine Staging

The revised ASRM staging system, is based on the appearance, size, and

depth of peritoneal and ovarian implants; the presence, extent, and type of

adnexal adhesions; and the degree of cul-de-sac obliteration (179,201). In this

classification system, the morphology of peritoneal and ovarian implants

should be categorized as red (red, red-pink, and clear lesions), white (white,

yellow-brown, and peritoneal defects), and black (black and blue lesions),

702according to color photographs provided by ASRM.

This system reflects the extent of endometriotic disease but has considerable

intraobserver and interobserver variability (245,246). [4] The ASRM

classification for endometriosis is subjective and correlates poorly with pain

and fertility outcomes (175). Despite these important shortcomings the WES

recommends its use because of two important reasons: it is the most widely used

staging system in clinical practice and endometriosis research, and it is the

rASRM system (partially) incorporated in the EFI and ENZIAN.

Endometriosis Fertility Index

[5] The EFI staging system predicts non-IVF pregnancy rates after surgical

staging and treatment of endometriosis (Fig. 13-7) (177). The EFI is based on

historical and surgical factors. The historical factors are age, years of

infertility, and prior pregnancies. The surgical factors consist of the total

ASRM score, the ASRM endometriosis score, and the least function score,

which describes functionality of the fallopian tubes, fimbriae, and ovaries.

The EFI was designed specifically for infertility patients who have had surgical

staging and treatment of their disease. It is not intended to predict any aspect of

endometriosis associated pain. It is required that the male and female gametes are

sufficiently functional to enable attempts at non-IVF conception. Severe uterine

abnormality that is clinically significant is not included in the EFI. However,

when this condition is found it does need to be taken into account in predicting

pregnancy rates.

ENZIAN Classification

The ENZIAN staging system supplements the rASRM staging with a precise

description of the location and extent of deep endometriosis lesions and the

involvement of retroperitoneal structures or other organs.

The anatomic location of the deep endometriotic lesions is described in three

compartments: A = rectovaginal septum and vagina; B = sacrouterine ligament to

pelvic wall; and C = rectum and sigmoid colon. The depth of invasion is rated for

all compartments (grade 1 = invasion <1 cm; grade 2 = invasion 1 to 3 cm; grade

3 = invasion >3 cm). Deep endometriotic lesions outside the pelvis and invasion

of organs is registered separately: FA = adenomyosis; FB = bladder; FU =

intrinsic involvement of the ureter; FI = intestinal disease cranial to the

rectosigmoid junction; and FO = other locations, such as abdominal wall

endometriosis. The ENZIAN classification seems to be useful in planning

endometriosis surgery, but more research is needed on the correlation with pain or

infertility and clinical relevant outcomes.

Spontaneous Evolution

Endometriosis appears to be a progressive disease in a significant proportion

(30% to 60%) of patients. During serial observations, deterioration (47%),

improvement (30%), or elimination (23%) was documented over a 6-month

period (247,248). In another study, endometriosis progressed in 64%, improved in

27%, and remained unchanged in 9% of patients over 12 months (249). A third

study of 24 women reported 29% with disease progression, 29% with disease

regression, and 42% with no change over 12 months. Follow-up studies in both

baboons and women with spontaneous endometriosis over 24 months

demonstrated disease progression in all baboons and in 6 of 7 women (250–252).

Several studies reported that subtle lesions and typical implants may represent

younger and older types of endometriosis, respectively. In a cross-sectional study,

the incidence of subtle lesions decreased with age (253). This finding was

confirmed by a 3-year prospective study that reported that the incidence, overall

pelvic area involved, and volume of subtle lesions decreased with age, but in

typical lesions, these parameters and the depth of infiltration increased with age

(7). Remodeling of endometriotic lesions (transition between typical and subtle

subtypes) is reported to occur in women and in baboons, indicating that

endometriosis is a dynamic condition (254,255). Several studies in women,

cynomolgus monkeys, and rodents showed that endometriosis is ameliorated after

pregnancy (255–258).

The characteristics of endometriosis are variable during pregnancy, and

lesions tend to enlarge during the first trimester but regress thereafter (259).

Studies in baboons revealed no change in the number or surface area of

endometriosis lesions during the first two trimesters of pregnancy (260). These

results do not exclude a beneficial effect that may occur during the third trimester

or in the immediate postpartum period. Establishment of a “pseudopregnant state”

with exogenously administered estrogen and progestins is based on the belief that

symptomatic improvement may result from decidualization of endometrial

implants during pregnancy (261). This hypothesis is not substantiated, and it is

possible that amenorrhea can explain the beneficial effect of pregnancy and

lactation on endometriosis-associated pain symptoms.

MANAGEMENT

Primary Prevention

No strategies to prevent endometriosis are uniformly successful. A reduced

incidence of endometriosis was reported in women who engaged in aerobic

activity from an early age, but the possible protective effect of exercise was not

investigated thoroughly (48). There is insufficient evidence that OC use offers

704protection against the development of endometriosis. One report showed an

increased risk for endometriosis in a select population of women taking OCs,

possibly explained by the observation that dysmenorrhea as a reason to initiate

estroprogestins is significantly more common in women with endometriosis than

in women without the disease (262,263). OCs inhibit ovulation, substantially

reduce the volume of menstrual flow, and may interfere with implantation of

refluxed endometrial cells, but the hypothesis of recommending OCs for primary

prevention of endometriosis is not sufficiently substantiated (264). Although the

risk of endometriosis appears reduced during OC use, it is possible that this effect

results from postponement of surgical evaluation caused by temporary

suppression of pain symptoms (265). Confounding by selection and indication

biases may explain the trend toward an increase in risk of endometriosis observed

after discontinuation, but further clarification is needed (265).

FIGURE 13-7 Endometriosis Fertility Index. (From Adamson D, Pasta D. Endometriosis fertility index: The new, validated endometriosis staging system. Fertil Steril

2010;94:1609–1615.)

Principles of Treatment

Treatment of endometriosis must be individualized, taking into consideration the clinical problem in its entirety, including the impact of the disease and the effect of its treatment on quality of life. Evidence-based recommendations that are continuously updated can be found in the ESHRE guidelines for the clinical management of endometriosis (1).

In most women with endometriosis, preservation of reproductive function

is desirable (1). Many women with endometriosis have pain and infertility at

the same time or may desire children after sufficient pain relief, which

complicates the choice of treatment. Endometriosis surgery should be

considered as reproductive surgery, defined by the World Health Organization

(WHO) as “all surgical procedures carried out to diagnose, conserve, correct

and/or improve reproductive function” (266). The least invasive and least

expensive approach that is effective with the least long-term risks should be

chosen (1). Symptomatic endometriosis patients can be treated with

analgesics, hormones, surgery, assisted reproduction, or a combination of

these modalities (1). Regardless of the clinical profile (infertility, pain,

asymptomatic findings), treatment of endometriosis may be justified because

endometriosis appears to progress in 30% to 60% of patients within a year of

diagnosis and it is not possible to predict in which patients it will progress

(249). Elimination of the endometriotic implants by surgical or medical treatment

often provides only temporary relief. In addition to eliminating the endometriotic

lesions, the goal should be to treat the sequelae (pain and infertility) often

associated with this disease and to prevent recurrence of endometriosis (1).

Endometriosis is a chronic disease and the recurrence rate is high after both

hormonal and surgical treatment (1).

Treatment of extragenital endometriosis will depend on the site. If

complete excision is possible, this is the treatment of choice; when this is not

possible, long-term medical treatment is necessary using the same principles

of medical treatment for pelvic endometriosis (1).

It is important to involve the patient in all decisions, to be flexible in

considering diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, and to maintain a good

relationship. It may be appropriate to seek advice from more experienced

colleagues or to refer the patient to a center with the necessary expertise to offer

treatments in a multidisciplinary context, including advanced laparoscopic

surgery and laparotomy (1,267). Because the management of severe or deep

endometriosis is complex, referral is strongly recommended when disease of such

707severity is suspected or diagnosed (1).

Treatment of Endometriosis-Associated Pain

Pain may persist despite seemingly adequate medical or surgical treatment of

the disease. A multidisciplinary approach involving a pain clinic and

counseling should be considered early in the treatment plan. The least

invasive and least expensive approach that is effective should be used (1).

Surgical Treatment

Depending on the severity of disease, diagnosis and removal of endometriosis

should be performed simultaneously at the time of surgery, provided that

preoperative consent was obtained (1,268–271). The goal of surgery is to excise

all visible endometriotic lesions and associated adhesions—peritoneal lesions,

ovarian cysts, deep rectovaginal endometriosis—and to restore normal

anatomy (1). Laparoscopy is preferred over laparotomy because the two

techniques are equally effective and laparoscopy is associated with quicker

recovery, better cosmesis, less postoperative pain, decreased costs, lower

morbidity, and fewer postoperative adhesions (1). Laparotomy is only

indicated in the rare cases of advanced-stage disease where laparoscopy is

impossible.

Conservative Surgery

Peritoneal Endometriosis

Endometriosis lesions can be removed during laparoscopy by surgical

excision with scissors, bipolar coagulation, or laser methods (CO2 laser,

potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser, or argon laser). Some surgeons claim that the

CO2 laser is superior because it causes only minimal thermal damage, but no

evidence is available to show the superiority of one technique over another.

Surgical ablation of peritoneal endometriosis is considered equally effective as

surgical excision. However, surgical excision of lesions could be preferred

because it allows histologic analysis and confirmation of endometriosis.

Ovarian Endometriosis

Superficial ovarian lesions can be vaporized. The surgical management of

pain associated with ovarian endometriotic cysts is controversial. The most

common procedures for the treatment of ovarian endometriomas are either

excision of the cyst wall or drainage and ablation of the cyst wall. During

excision, the ovarian endometrioma is aspirated, followed by incision and

removal of the cyst wall from the ovarian cortex with maximal preservation of

708normal ovarian tissue. During drainage and ablation, the ovarian endometrioma is

aspirated and irrigated. Its wall can be inspected with ovarian cystoscopy for

intracystic lesions, and it is vaporized to destroy the mucosal lining of the cyst.

According to a systematic review, there is good evidence that excisional

surgery for endometriomas with a diameter of 3 cm provides a more favorable

outcome than drainage and ablation with regard to the recurrence of the

endometrioma, recurrence of pain symptoms, and in women who were previously

subfertile or had subsequent spontaneous pregnancy (272). Laparoscopic excision

of the cyst wall of the endometrioma was associated with a reduced recurrence

rate of the symptoms of dysmenorrhea (odds ratio [OR] 0.15; 95% CI, 0.06–

0.38), dyspareunia (OR 0.08; 95% CI, 0.01–0.51), and nonmenstrual pelvic pain

(OR 0.10; 95% CI, 0.02–0.56), a reduced rate of recurrence of the endometrioma

(OR 0.41; 95% CI, 0.18–0.93), and with a reduced requirement for further

surgery (OR 0.21; 95% CI, 0.05–0.79) than surgery to ablate the endometrioma.

For those women subsequently attempting to conceive, it was associated with an

increased spontaneous pregnancy rate in women who had documented prior

infertility (OR 5.21; 95% CI, 2.04–13.29).

Based on this evidence, the ESHRE guideline recommends cystectomy over

drainage and coagulation because a cystectomy reduces endometriosisassociated pain and has a lower recurrence rate. In case of very large

endometriomas where excision is technically difficult without removing a large

part of the ovary, a three-step procedure (marsupialization and rinsing followed

by hormonal treatment with GnRH analogs and cyst wall electrocoagulation or

laser vaporization 3 months later) can be considered (1,273).

It is possible that the surgical techniques used to treat ovarian endometriotic

cysts may influence postoperative adhesion formation and/or ovarian function. In

a randomized study comparing surgical methods to achieve ovarian hemostasis

after laparoscopic endometriotic ovarian cystectomy, closure of the ovary with an

intraovarian suture resulted in a lower rate and extension of postsurgical ovarian

adhesions at 60 to 90 days follow-up when compared to only bipolar coagulation

on the internal ovarian surface (274).

Deep Endometriosis

Deep endometriosis is usually multifocal and complete surgical excision must

be performed in a one-step surgical procedure in order to avoid more than

one surgery, provided the patient is fully informed (1,173,269). Because