Vulvar Cancer

BS. Nguyen Hong Anh

KEY POINTS

1 Vulvar lesions require biopsy to avoid delay in diagnosis.

2 The modern approach to patients with vulvar cancer is multidisciplinary and

individualized.

3 Management of the primary lesion and groin nodes is determined separately.

4 Most T1 and early T2 lesions can be managed with radical local excision.

5 Large T2 and T3 primary tumors are best treated with chemoradiation followed by

limited surgical resection.

6 Unifocal tumors less than 4 cm in diameter with clinically negative nodes are suitable

for sentinel lymph node dissection in experienced hands.

7 When groin dissection is indicated, it should be a thorough inguinofemoral

lymphadenectomy.

8 The single most important prognostic factor is lymph node status: 5-year survival

without groin node metastases is greater than 90%; with groin node metastases, 5-

year survival is 50%.

9 Postoperative (chemo-) radiation decreases the risk of groin recurrence in patients

with multiple positive inguinofemoral lymph nodes.

10 Recurrence in the groin is almost universally fatal.

With 6,020 new cases and 1,150 deaths annually in the United States, vulvar

cancer is uncommon, resulting in age-adjusted incidence rates of 2.8 and 1.7 per

100,000 in white and black women, respectively. Vulvar cancer represents about

4% to 6% of malignancies of the female genital tract and 0.6% of all cancers in

women (1,2). Vulvar cancer predominantly affects postmenopausal women, and it

is the most common anogenital cancer in women more than 70 years of age (3).

HPV infection is associated with a significant number of vulvar cancers. [1] The

incidence of in situ vulvar cancer has been increasing worldwide, primarily

because of the increasing occurrence in young women, who account for 75%

of the cases. The incidence of lichen sclerosus, which is associated with an

increased risk of vulvar cancer, has doubled over the past two decades,

predominantly in postmenopausal women (4). The overall rate of invasive

vulvar carcinoma is increasing, but at a much lower rate (5,6). Squamous cell

carcinomas account for over 80% of all primary vulvar malignancies, whereas

melanomas, adenocarcinomas, basal cell carcinomas, Paget disease, and sarcomas

2695are less common. Most vulvar cancers are diagnosed at an early stage. In the

United States, 5-year survival rates for vulvar cancer are 72%.

Following the initial reports of Taussig in the United States and Way in Great

Britain, radical vulvectomy and en bloc groin dissection, with or without pelvic

lymphadenectomy, was standard treatment for all patients with operable disease

(7,8). Postoperative morbidity was high and prolonged hospitalization common.

Over the past 4 decades, significant advances in the management of vulvar

cancer have been made, reflecting a paradigm shift toward a more

conservative surgical approach without compromised survival and with

markedly decreased physical and psychological morbidity:

1. [2] Individualization of treatment for all patients with invasive disease.

2. Vulvar conservation for patients with unifocal tumors and an otherwise

normal vulva.

3. Omission of the groin dissection for patients with microinvasive tumors

(T1a, Ä2 cm diameter and Ä1 mm of stromal invasion).

4. Elimination of routine pelvic lymphadenectomy.

5. Incorporation of the sentinel lymph node procedure to eliminate complete

inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy in node-negative patients who may not

derive benefits from the procedure.

6. The use of separate incisions for the groin dissection to improve wound

healing.

7. Omission of the contralateral groin dissection in patients with lateral T1

lesions and negative ipsilateral nodes.

8. The use of preoperative radiation therapy to obviate the need for

exenteration in patients with advanced disease.

9. The use of postoperative (chemo-) radiation therapy to decrease the

incidence of groin recurrence in patients with multiple positive groin

nodes.

ETIOLOGY

The etiology of vulvar cancer is multifactorial. Reported risk factors for vulvar

cancer include human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, vulvar intraepithelial

neoplasia (VIN), cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), lichen sclerosus,

cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity, immunosuppression, a prior

history of cervical cancer, and northern European ancestry (9,10). Growing

evidence has established two distinct etiologic entities of squamous cell

carcinoma of the vulva:

26961. Basaloid or warty types, which comprise about 40% of vulvar squamous

cell carcinomas, tend to be multifocal, occur generally in younger

patients, and are related to HPV infection, usual type VIN (uVIN),

immunosuppression, and cigarette smoking.

2. Keratinizing, differentiated, or simplex types, which account for about 60%

of cases, tend to be unifocal, occur predominantly in older patients, are

not related to HPV, and often are found in areas adjacent to lichen

sclerosus, chronic inflammatory dermatoses, and differentiated type VIN

(dVIN).

High-grade VIN was closely studied as a potential precancerous lesion. The

direct progression of VIN to cancer is difficult to document, but a review of 3,322

published patients with high-grade VIN reports a 9% progression rate to cancer

for untreated and 3.8% for treated cases (11). VIN is found adjacent to basaloid or

warty vulvar squamous cell carcinomas in more than 80% of cases and 10% to

20% of vulvar carcinoma in situ lesions harbor an occult invasive component

(12,13). A meta-analysis comprising 5,015 vulvar cancers demonstrated a 40%

prevalence of HPV in vulvar cancer with nearly 80% of warty or basaloid cancers

testing positive for HPV, compared with only 13% of keratinizing carcinomas.

The predominant high-risk HPV type was HPV16, followed by HPV33 and

HPV18 (14). Epidemiologic risk factors for the basaloid or warty-type

squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva are similar to those for cervical cancer

and include a history of multiple lower genital tract neoplasias,

immunosuppression, and smoking. Based on immunogenicity and efficacy

studies, it is expected that HPV vaccination, particularly with the nine-valent

HPV vaccine, has the potential to prevent up to 90% of HPV-associated vulvar

cancers (15).

Frequently implied as an etiologic variable for the keratinizing carcinoma is the

itch–scratch cycle associated with lichen sclerosus and chronic inflammatory

dermatoses, with atypical changes occurring in the repaired epithelium.

Differentiated VIN is a precursor to keratinizing squamous cell carcinoma and is

strongly associated with lichen sclerosus. In keratinizing carcinoma, adjacent

lichen sclerosus or dVIN is found in more than 80% of patients (4). Women with

vulvar lichen sclerosus are at increased risk of developing invasive squamous

cell cancer of the vulva. A population-based study found a 36-fold increased risk

of vulvar cancer for women with lichen sclerosus (16). During the past 20 years,

the incidence of lichen sclerosus has nearly doubled from 7.4 to 14.6 per 100,000

woman-years. In a cohort of more than 3,000 women with lichen sclerosus, the

observed cumulative incidence of squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva was

6.7% with concurrent VIN and age ≥70 years being independent risk factors (4).

2697Supportive evidence that some of these lesions are precancerous comes from

molecular studies that demonstrate aneuploid DNA content, p53 overexpression,

high Ki67 expression, indicating high proliferation indices and monoclonal

expansion of keratinocytes in lichen sclerosus and dVIN (17–19), though the

exact molecular mechanism of non–HPV-associated vulvar cancer remains to be

elucidated. An area of active research explores whether treatment of lichen

sclerosus with superpotent topical steroids can impact the malignancy risk (20). A

prospective longitudinal cohort study of 507 women with biopsy-proven vulvar

lichen sclerosus demonstrated that patients who were compliant with active

treatment, typically with superpotent topical steroids, had improved symptom

control and a reduced incidence of vulvar carcinoma (21).

TYPES OF INVASIVE VULVAR CANCER

The histologic subtypes of invasive vulvar cancer are shown in Table 40-1.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Approximately 90% to 92% of all invasive vulvar cancers are of the

squamous cell type. Squamous carcinomas of the vulva can be divided into

distinct histologic subtypes designated as basaloid carcinoma, warty carcinoma,

and keratinizing squamous carcinoma. Mitoses are noted in these malignancies,

but atypical keratinization is the histologic hallmark of invasive vulvar cancer

(23). Most vulvar squamous carcinomas reveal keratinization (Fig. 40-1).

Histologic features that correlate with the occurrence of inguinal lymph node

metastasis are lymph–vascular space invasion, tumor thickness, depth of stromal

invasion, grade of differentiation, histologic pattern of invasion (spray and stellate

versus confluent, compact, broad, and pushing), and increased amount of keratin

(24–27).

Table 40-1 Malignant Tumors of the Vulva Based on IARC/WHO Classification (22)

Type Percent

Malignant Epithelial Tumors

Squamous cell carcinoma (keratinizing, non-keratinizing, basaloid,

warty, verrucous)

90–

92%

Basal cell carcinoma 2–

3%

Paget disease <1%

2698Bartholin gland (adenocarcinoma, squamous cell, adenosquamous,

adenoid cystic, transitional cell)

1%

Tumors arising from other specialized anogenital glands

(adenocarcinoma of mammary gland type, adenocarcinoma of Skene

gland or minor vestibular gland origin, malignant Phylloides tumor)

<1%

Adenocarcinomas of other types (sweat gland type, intestinal type) <1%

Malignant Neuroectodermal Tumors <1%

Ewing sarcoma

Malignant Soft Tissue Tumors <1%

Rhabdomyosarcoma

Leiomyosarcoma

Epithelioid sarcoma

Alveolar soft part sarcoma

Other sarcomas

Malignant Melanocytic Tumors

Malignant melanoma 2–

5%

Malignant Germ Cell Tumors <1%

Neuroendocrine tumors (small cell or large cell high-grade

neuroendocrine carcinoma)

Merkel cell tumor

Yolk sac tumor

Lymphoid and Myeloid Tumors <1%

Lymphomas

Myeloid neoplasms

Secondary (metastatic) Tumors 1%

2699IARC, International Agency for Research on Cancer; WHO, World Health Organization.

[3] Microinvasive carcinoma of the vulva (T1a) is defined as a lesion 2 cm

or less in diameter with 1 mm or less stromal invasion (28). Depth of stromal

invasion is measured vertically from the epithelial–stromal junction (basement

membrane) of the adjacent most superficial dermal papilla to the deepest point of

tumor invasion (Fig. 40-2). When the tumor invades 1 mm or less, metastasis to

the inguinal lymph nodes is extremely rare among reported series. When

invasion is greater than 1 mm, there is a significant risk of inguinal lymph

node metastasis.

Clinical Features

[4] Squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva is predominantly a disease of

postmenopausal women. The mean age at diagnosis is about 65 years and

15% of patients who develop vulvar cancer do so before age 40. There may

be a longstanding history of an associated vulvar intraepithelial disorder,

such as lichen sclerosus or VIN. As many as 27% of patients with vulvar

cancer have a second primary malignancy (29–31). Based on data from the

National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER)

program, patients with invasive vulvar cancer have an increased risk of 1.3% for

developing a subsequent cancer. Most of the excess second cancers were

smoking related (e.g., cancers of the lung, buccal cavity and pharynx, esophagus,

nasal cavity, and larynx) or related to infection with HPV (e.g., cervix, vulva,

vagina, and anus) (32).

Most patients are asymptomatic at the time of diagnosis. If symptoms exist,

vulvar pruritus, a lump, or a mass are the most common findings. Less frequent

symptoms include a bleeding or ulcerative lesion, discharge, pain, or dysuria.

Occasionally, a large metastatic mass in the groin is the initial symptom.

A careful inspection of the vulva should be part of every gynecologic

examination. On physical examination, vulvar carcinoma is usually raised and

may be fleshy, ulcerated, plaquelike, or warty in appearance. It may be

pigmented, red or white, and tender or painless. The lesion may be clinically

indistinct, especially in the presence of VIN, lichen sclerosus, or other vulvar

dermatoses (13). Any lesion of the vulva warrants a biopsy.

FIGURE 40-1 Squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva, keratinizing type. The multiple

pearl formations consist of laminated keratin.

FIGURE 40-2 Early invasive carcinoma of vulva originating from vulvar intraepithelial

neoplasia. An irregular nest of malignant cells extend from the base of rete pegs.

Desmoplastic stromal reaction and chronic inflammation are useful diagnostic signs of

stromal invasion. The depth of stromal invasion is measured from the base of the most

superficial dermal papilla vertically to the deepest tumor cells.

Most squamous carcinomas of the vulva occur on the labia majora and

minora (60%), but the clitoris (15%) and perineum (10%) may be primary

sites. Approximately 10% of the cases are too extensive to determine a site of

origin, and about 5% of the cases are multifocal.

As part of the clinical evaluation, a careful assessment of the extent of the

lesion, including whether it is unifocal or multifocal, should be performed. The

lesion diameter should be measured and its proximity to the midline and/or

involvement of midline structures including urethra, vagina, clitoris, and anus

should be assessed. The groin lymph nodes should be evaluated carefully, and a

complete pelvic examination should be performed. A cytologic sample should be

taken from the cervix, and colposcopy of the vulva, cervix, and vagina should

be performed because of the common association with other squamous

2702intraepithelial or invasive neoplasms of the lower genital tract.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis requires a Keys punch biopsy or wedge biopsy, which can be

obtained in the office using local anesthesia. The biopsy must include sufficient

underlying dermis to assess for microinvasion.

Physician delay is a common problem in the diagnosis of vulvar cancer,

particularly if the lesion has a warty appearance. Any large or confluent

warty lesion requires biopsy before medical or ablative therapy is initiated.

Routes of Spread

Vulvar cancer spreads by the following routes:

1. Direct extension, to involve adjacent structures such as the vagina, urethra,

clitoris, and anus.

2. Lymphatic embolization to the regional inguinal and femoral lymph nodes.

3. Hematogenous spread to distant sites, including the lungs, liver, and bone.

[5] Lymphatic metastases may occur early in the disease. Twelve percent of

tumors 2 cm in diameter or smaller have regional metastases (29,33).

Initially, spread is usually to the inguinal lymph nodes, which are located between

Camper’s fascia and the fascia lata (34). From these superficial groin nodes, the

disease spreads to the deep femoral nodes, which are located medial to the

femoral vessels (Fig. 40-3). Cloquet’s or Rosenmüller’s node, situated beneath the

inguinal ligament, is the most cephalad of the femoral node group. Metastases to the

femoral nodes without involvement of the inguinal nodes are reported (35–

38). A study from the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center reported a 9% groin

recurrence rate in 104 patients with vulvar cancer who had negative nodes on

superficial inguinal lymphadenectomy at initial surgery, and intraoperative

lymphatic mapping studies found the sentinel node deep to the cribriform fascia

in 5% to 16% of these cases (39–41). This pattern of lymphatic spread needs to be

taken into consideration when determining the extent of inguinofemoral

lymphadenectomy and the radiotherapeutic techniques and target volumes.

From the inguinal–femoral nodes, the cancer spreads to the pelvic nodes,

particularly the external iliac group. Although direct lymphatic pathways from

the clitoris and Bartholin gland to the pelvic nodes were described, these channels

seem to be of minimal clinical significance (42–44). The lymphatics from either

side of the vulva form a rich network of anastomoses along the midline.

Lymphatic drainage from the clitoris, anterior labia minora, and perineum is

bilateral. Metastases to contralateral lymph nodes in the absence of ipsilateral

2703nodal involvement is very rare (0% to 0.4%) for lateral vulvar tumors that are

either 2 cm or less in diameter or with 5 mm or less invasion (33,45).

The overall incidence of inguinal–femoral lymph node metastases is

reported to be about 32% (38,40,43–53) (Table 40-2). Metastases to pelvic

nodes occur in about 12% of cases. Pelvic nodal metastases are rare (0.6%) in

the absence of groin node involvement, but they occur in about 16% of cases with

positive groin nodes (Table 40-2). The risk increases to 33% in the presence of

clinically suspicious groin nodes and to 40% to 50% if there are three or more

pathologically positive inguinal–femoral nodes (30,45,54–57). The incidence of

lymph node metastases correlates positively with depth of invasion, as shown in

Table 40-3. Hematogenous spread usually occurs late in the course of vulvar

cancer and is rare in the absence of lymph node metastases.

FIGURE 40-3 Inguinal–femoral lymph nodes. (From Hacker NF. Vulvar and Vaginal

Cancer. In: Hacker NF, Gambone J, Hobel C. Hacker & Moore’s Essentials of Obstetrics

and Gynecology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2015:452, with permission.)

Table 40-2 Incidence of Lymph Node Metastases in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the

Vulva

2704Staging

Initially, vulvar carcinoma was staged clinically based on tumor size and location,

palpable regional lymph node status, and a limited search for distant metastases.

The prognostic importance of the lymph node status is significant, but clinical

assessment of the lymph nodes has limited accuracy. This led the Cancer

Committee of FIGO to introduce a surgical staging system for vulvar cancer in

1988, which underwent several revisions, most recently in 2009, to provide better

prognostic discrimination between stages and less heterogeneity within stages

(28,58,59) (Table 40-4), by separating patients whose tumors involve adjacent

perineal structures from those with positive lymph nodes and taking into account

the number and morphology of the involved nodes.

The new FIGO staging system was validated in 269 patients, 42% of whom

were restaged (61). The number of positive nodes negatively correlated with

survival, as did the presence of extracapsular growth. This study confirmed

Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) and SEER data indicating that in patients

with negative nodes, tumor size was not predictive of survival (59). This study

confirmed reports demonstrating that, when corrected for the number of positive

nodes, bilaterality of nodal metastases was not predictive of survival (61–65).

Paralleling the changes to the FIGO staging, the American Joint Committee on

Cancer (AJCC) significantly modified the vulvar cancer tumor-node-metastasis

(TNM) classification with the release of the 2009 edition of the AJCC Cancer

Staging Manual (Table 40-4) (60).

2705Table 40-3 Nodal Status in T1 Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Vulva Versus Depth

of Stromal Invasion

Depth of Invasion No. of Patients Positive Nodes Nodes

1 mm 163 0 0

1.1–2 mm 145 11 7.7

2.1–3 mm 131 11 8.3

3.1–5 mm 101 27 26.7

>5 38 13 34.2

Total 578 62 10.7

From Hacker NF, Eifel PJ. Vulvar cancer. In: Berek JS, Hacker NF. Berek & Hacker’s

Gynecologic Oncology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:569.

Table 40-4 The 2009 FIGO Staging and TNM Classification for Vulvar Cancer

(28,61)

FIGO Stage TNM Classification Clinical/Pathologic Findings

Stage IA T1aN0M0 Lesions ≤2 cm in size, confined

to the vulva or perineum and with

stromal invasion ≤1 mm,a no

nodal metastasis

Stage IB T1bN0M0 Lesions >2 cm in size or with

stromal invasion >1 mm,

confined to the vulva or

perineum, with negative nodes

Stage II T2N0M0 Tumor of any size with extension

to adjacent perineal structures

(1/3 lower urethra, 1/3 lower

vagina, anus) with negative nodes

Stage III Tumor of any size with or without

extension to adjacent perineal

structures (1/3 lower urethra, 1/3

lower vagina, anus) with positive

inguinofemoral lymph nodes

2706IIIA T1or2 N1b M0 T1or2 N1a

M0

(i) with 1 lymph node metastasis

(≥5 mm) or (ii) 1–2 lymph node

metastasis(es) (<5 mm)

IIIB T1or2 N2b M0 T1or2 N2a

M0

(i) with 2 or more lymph node

metastasis (≥5 mm) or (ii) 3 or

more lymph node metastases (<5

mm)

IIIC T1or2 N2c M0 with positive nodes with

extracapsular spread

Stage IV Tumor invades other regional (2/3

upper urethra, 2/3 upper vagina),

or distant structures

IVA T3Nany M0 TanyN3 Tumor invades any of the

following:

(i) Upper urethral

and/or vaginal

mucosa, bladder

mucosa, rectal

mucosa, or fixed to

pelvic bone

(ii) Fixed or

ulcerated inguinofemoral lymph

nodes

IVB T

anyNanyM1 Any distant metastasis including

pelvic lymph nodes

TNM

Classification

T: Primary tumor N: Regional lymph nodes

(femoral and inguinal nodes)

T

x: Primary tumor cannot

be assessed

N

x: Regional lymph nodes cannot

be assessed

T0: No evidence of

primary tumor

N0: No regional lymph node

metastases

Tis: Carcinoma in situ

(preinvasive carcinoma)

N1: One or two regional lymph

node metastases with the

2707following features:

T1a: Lesions ≤2 cm in

size, confined to the vulva

or perineum and with

stromal invasion ≤1 mm

N1a: One or two lymph node

metastases each <5 mm

T1b: Lesions >2 cm in size

or any size with stromal

invasion >1 mm, confined

to the vulva or perineum

N1b: One lymph node metastasis

≥5 mm

T2: Tumor of any size

with extension to adjacent

perineal structures (lower

1/3 of urethra, lower of

1/3 vagina, anal

involvement)

N2: Regional lymph node

metastases with the following

features:

T3: Tumor of any size

with extension to any of

the following:

N2a: ≥3 lymph node metastases,

each <5 mm in diameter

upper 2/3 of urethra, upper

2/3 of vagina, bladder

mucosa, rectal mucosa, or

fixed to pelvic bone

N2b: ≥2 lymph node metastases

≥5 mm

M1: Distant metastasis

(including pelvic lymph

node metastasis)

N2c: Lymph node metastases with

extracapsular spread

N3: Fixed or ulcerated regional

lymph node metastasis

M: Distant metastasis

M0: No distant metastasis

aThe depth of stromal invasion is measured from the epithelial–stromal junction of the

adjacent most superficial dermal papilla to the deepest point of invasion.

FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; TNM, tumor node

metastasis.

FIGO Committee on Gynecologic Oncology. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the

vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2009;105:103–104 (31); American

Joint Committee on Cancer. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th ed. Chicago, IL:

Springer New York, Inc.; 2010.

Table 40-5 Five-Year Survival for Patients With Vulvar Carcinoma (28)

FIGO Stage No. of Patients 5-Year Survival (%)

I 286 (34%) 79

II 266 (32%) 59

III 216 (26%) 43

IV 71 (8%) 13

FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

Prognosis and Survival

Survival of patients with vulvar cancer correlates with FIGO stage (66). The

prognosis for patients with early-stage disease is generally good (Table 40-5).

The single most important prognostic factor is lymph node status (51–

53,56,67,68). A report from the Mayo Clinic on 330 patients with primary

squamous cell carcinoma of the vulva demonstrated a significant correlation

between lymph node status and risk of treatment failure, especially in the first 2

years following initial therapy: 44.2% overall recurrence rate with positive versus

17.5% with negative lymph nodes. [6] More than one-third of relapses

presented 5 years or more after initial therapy (69). There is a strong negative

correlation between the number of positive lymph nodes and survival (Table 40-6).

Patients with negative lymph nodes have a 5-year survival rate of over 80%;

for patients with positive nodes, 5-year survival falls below 50%. The number

of positive nodes is of critical importance: Patients with one microscopically

positive lymph node have a prognosis similar to those with all negative lymph

nodes, whereas patients with three or more positive nodes have a poor

prognosis and a 2-year survival rate of 20% (70). The survival rate for patients

with positive pelvic nodes is about 11% (71). In addition to the number of nodes

involved, the morphology of the positive groin nodes is of prognostic

significance. As demonstrated in several studies, significant negative predictors of

survival are the size of the nodal metastasis, the proportion of the node replaced

by tumor cells, and the presence of any extracapsular spread (59,67,72,73).

Histologic grade, tumor thickness, depth of stromal invasion, and lymph–vascular

space involvement contribute to the risk of lymph node involvement but are not

independent predictors of survival (70).

2709Post-treatment surveillance as recommended by the Society of Gynecologic

Oncology entails serial reviews of systems and careful physical examination with

annual cervical/vaginal cytology and imaging reserved for patients where findings

are concerning for recurrent disease (74). The frequency of surveillance visits

depends on the stage and recurrence risk:

Stage I, II disease every 6 months in years 1 and 2, and annually thereafter.

Stage III/IV disease every 3 months for the first two years, every 6 months

in years 3 to 5, and annually thereafter.

Table 40-6 Five-Year Survival for Patients With Vulvar Squamous Cell Carcinoma

by Number of Lymph Node Metastases (28)

No. of Lymph Node Metastases No. of Patients 5-Year Survival (%)

0 302 (61%) 81

1 66 (13%) 63

2 43 (9%) 30

3 24 (5%) 19

4 or more 62 (12%) 13

Treatment

[7] To individualize the patient’s care and determine the appropriate

therapy, it is necessary to independently manage the primary lesion and

groin lymph nodes using a separate incision technique for resection of the

vulvar lesion and for the node dissection. This is associated with lower

morbidity and metastases rarely occur in the skin bridge between vulva and

groin in patients without clinically suspicious inguinofemoral nodes (75,76).

Before initiation of therapy, all patients should undergo a careful clinical

examination, and colposcopy of the cervix, vagina, and vulva. Preinvasive (and

rarely invasive) lesions may be present at other sites along the lower genital tract,

and vulvar cancer is frequently multifocal. If disease is locally advanced, an

examination under anesthesia may be required to determine its full extent.

Imaging with PET/CT or MRI is performed for all but T1a lesions to aid in

assessment of the local disease and evaluate for metastases.

Management of the Primary Lesion

Microinvasive Vulvar Cancer (T1a)

2710[8] Tumors 2 cm or less in diameter with 1 mm or less invasion are

appropriately treated with a wide local excision, which is as effective as

radical surgery for the prevention of vulvar recurrences for these tumors

(77). The excision should go sufficiently deep into the dermis that depth of

invasion is fully assessed.

Early Vulvar Cancer (T1b)

[9] The modern approach to the management of patients with T1b

carcinoma of the vulva should be individualized. There is no standard approach

applicable to every patient, and emphasis is on performing the most conservative

operation that is consistent with cure of the disease through radical local excision

and surgical lymph node assessment while minimizing anatomic alterations and

disfigurement. An analysis of the literature indicates that the incidence of local

invasive recurrence after radical local excision or radical hemivulvectomy is not

higher than that after the historically performed radical vulvectomy (33,46,71,78–

80). In the presence of an otherwise normal-appearing vulva, radical local

excision is a safe surgical option, regardless of the size of the tumor or the

depth of invasion. Based on cumulative data of 413 patients reported in four

studies, an 8 mm or greater histopathologic resection margin results in a high rate

of local disease control (78,81–83). Of the 252 patients whose tumors were

resected with margins of 8 mm or greater, 2.4% experienced a local recurrence,

compared with 30.3% of the 161 patients whose margins were less than 8 mm.

Neither clinical tumor size nor the presence of coexisting benign vulvar pathology

correlated with local recurrence. It is important to bear in mind that paraffinembedded tissue shrinks by 20% to 25%. At the time of radical local excision,

at least a 1-cm grossly negative margin, without putting the skin under

tension, should be obtained and extended down to the level of the inferior

fascia of the urogenital diaphragm.

When vulvar cancer arises in the presence of VIN, lichen sclerosus, or some

nonneoplastic epithelial disorder, treatment is influenced by the patient’s age,

treatment history, and symptomatology. Elderly patients who often had many

years of chronic itching may not be disturbed by the prospect of a vulvectomy. In

younger women, it is desirable to conserve as much of the vulva as possible.

Radical local excision should be performed for the invasive disease, and the

associated intraepithelial disease should be treated in the manner most appropriate

to the patient. For example, topical steroids may be required for lichen sclerosus,

whereas VIN may require superficial local excision with primary closure,

ablation, topical therapy, or a combination thereof.

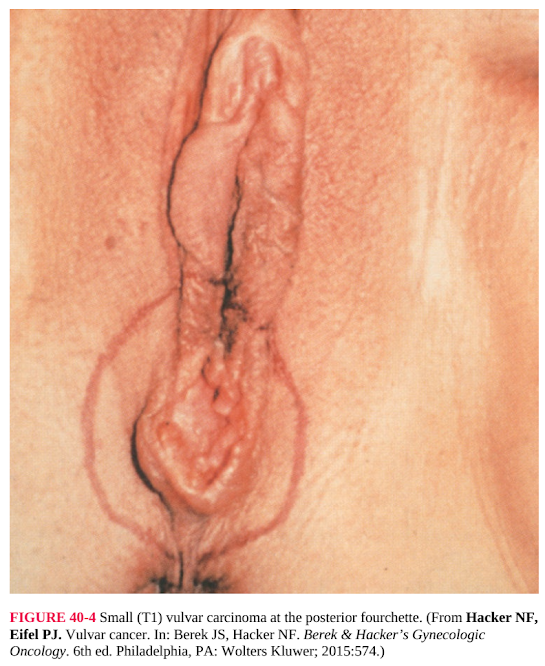

FIGURE 40-4 Small (T1) vulvar carcinoma at the posterior fourchette. (From Hacker NF,

Eifel PJ. Vulvar cancer. In: Berek JS, Hacker NF. Berek & Hacker’s Gynecologic

Oncology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:574.)

Radical local excision is most appropriate for lesions on the lateral or

posterior aspects of the vulva (Fig. 40-4). Midline lesions pose special

challenges because of their proximity to clitoris, urethra, or anus. For anterior

lesions, conservative clitoris-sparing surgery allows for excellent local control as

2712long as pathologic margins are at least 8 mm (84). For tumors that involve the

clitoris or that are in close proximity to it, any type of surgical excision will have

psychosexual consequences. In addition, marked edema of the posterior vulva

may occur. For young patients with periclitoral lesions, the primary lesion can be

treated with a small field of radiation therapy with concomitant sensitizing

chemotherapy. Small vulvar lesions should respond very well to about 5,000 cGy

external radiation, and biopsy can be performed after therapy to confirm the

absence of any residual disease (58).

Early T2 Vulvar Cancer

[10] The indications for vulvar conservation can be extended to selected

patients with early T2 tumors. The tumor-free margin should be the same,

whether or not a radical vulvectomy or a radical local excision is performed.

It seems feasible and desirable to extend the indications for vulvar

conservation, particularly for younger patients. Tumors that are suitable for

a conservative resection are those involving the posterior vulva and lower

vagina, where preservation of the anus, clitoris, and urethra is feasible.

For patients with more advanced T2 lesions, management consists of radical

vulvectomy and/or chemoradiation therapy. When the disease involves the distal

urethra or anus, partial resection of these organs would be required. Thus, it is

often preferable to give preoperative radiation therapy with chemosensitization to

allow for a less radical resection depending on location and response.

Closure of Large Defects

After radical local excision, primary closure without tension can be

accomplished for smaller defects. If an extensive dissection is required to

treat a large primary lesion, a number of options are available to repair the

defect based on the defect location, dimension, patient age, and

comorbidities:

1. An area may be left open to granulate, which it will usually do over a period of

6 to 8 weeks (85); this may be hastened by the application of vacuum-assisted

wound closure and negative pressure dressings (86).

2. Full-thickness rotational or advancement fasciocutaneous flaps may be

devised, such as the rhomboid flap, the mons pubis pedicle flap, the pudendal

thigh flap, or the V-Y-advancement flap (87–91). Fasciocutaneous flaps are

reliable and can be transferred as pedicle or island flaps (92). For the lower

and mid vulva, a V-Y gluteal fold flap may be preferred because of the good

esthetic outcome and well-concealed donor scar (91,93).

3. A broad range of myocutaneous flaps have been used for vulvar reconstruction

2713to cover large defects. These include unilateral or bilateral gracilis

myocutaneous grafts or a vertically oriented rectus abdominis muscle flap.

Because the graft brings a new blood supply to the area, it is particularly

applicable if the vulva is poorly vascularized from prior surgical resection or

radiation (91,93,94). Disadvantages include complexity and duration of the

procedure, the bulkiness of the flap, and donor-site sequelae.

Advanced Disease: Large T2 and T3 Primary Tumors

Treatment of locally advanced vulvar cancer remains challenging. To achieve

primary surgical clearance for tumors involving the upper urethra, anus, rectum,

or rectovaginal septum, pelvic exenteration is needed in addition to radical

vulvectomy and inguinal–femoral lymphadenectomy, which carries an extremely

high physical and psychological morbidity (95,96). Reported 5-year survival rates

with this approach are about 50% (97–99), with survival being significantly

determined by lymph node status. A series including 57 patients undergoing

primary anovulvectomy reported a median survival of 69 months with 59% of

patients experiencing one or more postoperative complications and 33% requiring

adjuvant therapy (100). For many of these patients, a combined approach of

chemoradiation therapy with or without subsequent surgery offers equal or

improved survival with reduced morbidity and may be the preferred treatment

approach. Numerous small prospective and retrospective series report on the use

of external beam radiation with concomitant chemotherapy to shrink the primary

tumor. Reported initial response rates to chemoradiation are 80% to 90%, and

operability is achieved in 63% to 92% of cases (101–109). This chemoradiation is

followed by a limited resection of the tumor bed on an individualized basis. Case

series suggest that approximately one-half of the specimens will contain residual

tumor, and local relapse rates are as high as 50% with external chemoradiation

alone (110). The GOG phase II study using a combination of weekly cisplatin

with radiation followed by surgical resection of gross residual disease, or biopsy

if clinically no residual cancer, resulted in a complete clinical response in 64% of

patients, with biopsy showing complete pathologic response in 50% of patients

without the need for posttreatment surgery in this subset of patients (111).

As experience with this combination therapy evolved, it appeared that external

beam therapy is appropriate for most cases, with more selective use of

brachytherapy. The extensiveness of the surgery is significantly modified. A

limited vulvar resection is advocated, and bulky N2 and N3 nodes are

resected without full groin lymphadenectomy to avoid the leg edema

associated with groin lymphadenectomy and radiation. With this combined

radiation–surgical approach, 5-year survival rates as high as 76% are

reported. With the experience accrued, preoperative radiation with concurrent

2714chemotherapy is regarded as the first treatment of choice for patients with

advanced vulvar cancer who would otherwise require some type of pelvic

exenteration or stoma. Neoadjuvant therapy is not justified in patients with tumors

that can be adequately treated with primary radical vulvectomy and bilateral groin

node dissection.

Management of the Lymph Nodes

Appropriate assessment for nodal involvement and groin dissection is the

single most important factor in decreasing the mortality from early vulvar

cancer. A careful examination of the groin is carried out as the presence of

clinically palpable inguinofemoral lymph nodes is an important determinant of

management.

When assessing a patient for groin dissection, the following facts should to be

kept in mind:

1. The only patients with virtually no risk of lymph node metastases are those

whose tumor is small (≤2 cm) and invades the stroma to 1 mm or less (T1a).

2. Patients who develop recurrent disease in an undissected groin have a greater

than 90% mortality (111).

3. Based on the laterality of the vulvar lesions and the status of the ipsilateral

groin, an ipsilateral or bilateral lymphadenectomy becomes necessary.

FIGURE 40-5 Skin incision for groin dissection through a separate incision. A line is

drawn 1 cm above and parallel to the groin crease, and a narrow ellipse of skin is removed.

(Revised with permission from Berek JS, Hacker NF. Practical Gynecologic Oncology.

2nd ed. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1994:418.)

Groin dissection is associated with postoperative wound infection and

breakdown. Although the incidence of wound breakdown is reduced significantly

when separate incisions are used for the groin dissection and drains are left in situ

until daily output is below 25 to 30 cc, lymphocyst formation and chronic leg

edema remain a major problem (Fig. 40-5) (77).

All patients whose tumors demonstrate more than 1 mm of stromal

invasion or whose tumors are larger than 2 cm (T1b and above) require

inguinal–femoral lymphadenectomy. If there is any question regarding the need

for inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy, a Keys biopsy or wedge biopsy of the

primary tumor should be obtained, and the depth of invasion should be

determined. If it is smaller than 1 mm on the wedge biopsy specimen, the entire

lesion should be locally excised and analyzed histologically to determine the

depth of invasion. If the lesion is 2 cm in diameter or smaller and there is no

invasive focus larger than 1 mm, groin dissection may be omitted, provided there

2716is no lymph–vascular space invasion and there are no clinically suspicious groin

lymph nodes. An occasional patient with less than 1 mm of stromal invasion has

documented groin node metastases, but the incidence is so low that it is of no

practical significance (112,113).

Inguinal–Femoral Lymphadenectomy

If groin dissection is indicated in patients with vulvar cancer, it should be a

thorough inguinal–femoral lymphadenectomy. The GOG reported six groin

recurrences among 121 patients with tumors 2 cm or less after a superficial

(inguinal) dissection, although the removed inguinal nodes were negative, and a

study from the M. D. Anderson Cancer Center reported a 9% groin recurrence

rate in 104 patients with vulvar cancer and negative nodes on superficial inguinal

lymphadenectomy (38,39). Although it is unclear whether all of these recurrences

were in the femoral nodes, both studies indicate that an incomplete groin

dissection will increase the number of groin recurrences and mortality. GOG data

indicate that radiation therapy cannot substitute for groin dissection followed by

selective radiation as indicated, even in patients with clinically nonsuspicious

lymph nodes (114). This GOG study was closed early because a significantly

higher incidence of recurrences occurred in women who were receiving groin

radiation therapy only (19% vs. 0%). The dose of radiation was 5,000 cGy given

in daily 200-cGy fractions to a depth of 3 cm below the anterior skin surface.

Although the radiation regimen prescribed was criticized extensively, other

uncontrolled studies give no evidence for better groin control with radiotherapy

(115,116). Surgery remains the treatment of choice for the groin for women with

vulvar cancer. Vulvar cancer patients with T2 or T3 lesions scheduled for primary

or neoadjuvant chemoradiation should undergo an inguinofemoral

lymphadenectomy prior to initiation of chemoradiation, given the lower survival

with primary groin radiation compared with groin dissection followed by

radiation (115). Some patients with T1b and T2 tumors and no palpable groin

lymph nodes on examination are candidates for sentinel lymph node assessment.

Unilateral Versus Bilateral Groin Dissection

It is not necessary to perform a bilateral groin dissection if the primary

lesion is unilateral and the ipsilateral lymph nodes are negative. In a patient

with a unilateral lesion and negative ipsilateral groin nodes, the risk of

contralateral lymph node metastasis is very low (33,45). In a study from the Mayo

Clinic, 8 of 163 patients with unilateral vulvar cancers (4.8%) had bilateral lymph

node metastases and only 3 (1.8%) had isolated contralateral lymph node

metastases. None of the patients with unilateral vulvar lesions that were either 2

cm or less or had 5 mm or less depth of invasion had bilateral groin node

2717involvement at diagnosis (45). There is an increase in the risk of contralateral

nodal involvement proportional to the number of positive ipsilateral inguinal

nodes (45,57). It is recommended that patients with any bulky or multiple

microscopically positive ipsilateral groin lymph nodes undergo contralateral

inguinal–femoral lymphadenectomy. Bilateral inguinal–femoral

lymphadenectomy should be performed for midline lesions (clitoris, anterior

labia minora, posterior fourchette) or those within 2 cm of the midline

because of the more frequent contralateral lymph flow from these regions

(117).

Management of Bulky Groin Nodes

All clinically or radiologically suspicious groin nodes should be resected if

deemed resectable and the patient is a surgical candidate. If nodal metastasis is

confirmed by preoperative biopsy or intraoperative frozen section, a full

inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy may be omitted to decrease morbidity with

subsequent radiation without compromising survival (118,119). If groin lymph

nodes are palpably enlarged, but frozen section does not demonstrate metastatic

disease, a complete inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy should be performed.

Patients with fixed, unresectable groin nodes should be treated with primary

chemoradiation. If there is no other evidence of metastatic disease following

chemoradiation, GOG data suggest that it may be appropriate to resect the

residual nodes (120).

Management of Pelvic Lymph Nodes

In the past, pelvic lymphadenectomy was part of the routine surgery for invasive

vulvar cancer. The incidence of pelvic lymph node metastasis is rare in the

absence of groin node involvement, and a more selective approach is preferred

(Table 40-2). Patients most prone to pelvic lymph node metastasis are those with

three or more pathologically positive groin nodes (30,42,54,121). In addition to

the number of nodes involved, the morphology of the positive groin nodes is of

prognostic significance. As demonstrated in several studies, significant negative

predictors of survival are the number of positive nodes, the size of the nodal

metastasis, the proportion of the node replaced by tumor cells, and the presence of

any extracapsular spread (63,67,72,73). In these patients, the pelvis requires

treatment by radiation. If a preoperative pelvic imaging study reveals bulky

pelvic lymph nodes, resection of these nodes should be performed via an

extraperitoneal approach prior to radiation because of the limited ability of

external beam radiation therapy to sterilize bulky positive pelvic nodes.

Sentinel Lymph Node Studies

Increasing evidence supports the use of intraoperative lymphatic mapping using

2718lymphoscintigraphy with technetium-99m-labeled nanocolloid and isosulfan blue

dye to identify a sentinel node that would predict the presence or absence of

regional nodal metastases. The strong interest in the sentinel node concept lies in

the desire to reduce the significant lifelong morbidity of lymphedema associated

with a thorough inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy, as only 25% to 35% of

patients with early-stage vulvar cancer will have lymph node metastases and thus

benefit from the procedure. Reliable identification of the sentinel node and

forgoing full lymphadenectomy in patients with clinically nonsuspicious groin

lymph nodes and a negative sentinel node significantly reduces the number of

patients who undergo unnecessary, extensive lymphadenectomy in the absence of

disease. This is contingent upon a negative sentinel lymph node reliably

predicting the absence of any other nodal metastases given the greater than 90%

mortality associated with a groin recurrence.

The sentinel lymph node procedure has led to a major decrease in

morbidity compared with a complete inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy

without negatively impacting prognosis in select patients (122–126). In

experienced hands, this procedure is reliable and suitable in early-stage

disease with unifocal tumor lesions less than 4 cm in size and clinically

negative lymph nodes on groin examination and imaging. A Cochrane

Database review of 34 studies evaluating 2,396 groins in 1,614 women reported

for blue dye plus technetium combined a sentinel node detection rate of 98% with

a pooled sensitivity estimate of 0.95 (95% CI 0.89 to 0.97), and a negative

predictive value of greater than 95% (127). The combination of blue dye and

radiocolloid is superior over blue dye alone for sentinel node identification.

Ultrastaging techniques such as serial micro-sectioning and

immunohistochemistry staining are used to detect micrometastases in the sentinel

node if initial hematoxylin and eosin section is negative. This increases the

detection rate of lymph node metastasis (123).

Recurrence in the groin is fatal in over 90% of patients. Thus, groin

recurrence is ultimately a critical outcome measure for surgical groin assessment

techniques. A meta-analysis of recurrence rate included 23 studies and

demonstrated a significantly higher groin recurrence rate with superficial inguinal

lymphadenectomy (6.6%; 95% CI 4.4–9.0) than with complete inguinofemoral

lymphadenectomy (1.4%; 95% CI 0.4–2.9) with the recurrence rate for patients

undergoing the sentinel node procedure being 3.4% (95% CI 1.8–5.4) (128).

Long-term follow-up of the GROINSS-V study, one of the largest studies on the

safety of the sentinel node procedure in vulvar cancer, reported for 377 patients

with unifocal <4 cm T1 vulvar cancer a local recurrence rate of 27.2% at 5 years

and 39.5% at 10 years. Isolated groin recurrences occurred in 2.5% of patients

with negative sentinel nodes and 8% of patients with positive sentinel nodes. All

2719groin recurrences occurred within 25 months of primary treatment (129). Some

small series of sentinel nodes in vulvar cancer with inclusion criteria similar to

those in GROINSS-V showed unexpectedly high false-negative rates of 8% to

27%, some of which may be attributable to patient selection and insufficient

experience of low-volume providers. This highlights the prerequisites for highquality sentinel node procedures, which include careful patient selection, trained

personnel, and appropriate infrastructure. The technique might otherwise carry

with it an unjustifiable rise in the frequency of groin recurrences.

Postoperative Management

Despite the age and general medical condition of many elderly patients with

vulvar cancer, surgery is usually remarkably well tolerated. Patients should be

able to commence eating a low-residue diet on the first postoperative day. In the

past, bed rest was advised for 3 to 5 days postoperatively to allow for

immobilization of the wounds and to foster healing. Because radical local

excisions are being performed with increasing frequency and groin

lymphadenectomy is done through separate incisions, patients begin

ambulation on postoperative day 1 or 2. Pneumatic calf compression and

subcutaneous low molecular weight heparin should be given to help prevent deep

venous thrombosis, and active leg movements are to be encouraged. Frequent

dressing changes are performed to keep the vulvar wound dry. Meticulous

perineal hygiene is maintained. Suction drainage of each side of the groin is

continued until output is minimal to help decrease the incidence of groin seromas.

It is not uncommon for suction drainage to continue for 10 or more days. The

Foley catheter is removed when the patient is ambulatory. If there is significant

periurethral swelling, prolonged bladder drainage may be advisable. If there is

breakdown of the vulvar wound, sitz bath or whirlpool therapy is helpful,

followed by drying of the perineum with a hair dryer.

Early Postoperative Complications

The major immediate morbidity is related to groin wound infection, necrosis, and

breakdown. This complication used to be reported in as many as 53% to 85% of

patients having an en bloc operation (29,30). With the separate-incision

approach, the incidence of wound breakdown has been reduced to approximately

44%; major breakdown occurs in about 14% of patients (31,75,130,131).

With appropriate antibiotics, debridement, and wound dressings, the area will

granulate and re-epithelialize over several weeks and may be managed with home

nursing. Whirlpool therapy is effective for areas of extensive breakdown. The

most common complication with the separate incision approach continues to be

wound infection requiring antibiotic therapy and lymphocyst formation, reported

2720in up to 40% of cases (131). The GROINSS-V study reported wound break down

of the groin in 34% of patients undergoing complete inguinofemoral

lymphadenectomy and 12% of patients undergoing the sentinel lymph node

procedure with respective cellulitis rates of 21% and 5% (122). Symptomatic

lymphocysts should be managed by periodic sterile aspiration.

Other early postoperative complications include urinary tract infection, seromas

in the femoral triangle, deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism,

myocardial infarction, hemorrhage, and, rarely, osteitis pubis. Anesthesia of the

anterior thigh resulting from femoral nerve injury is common and usually resolves

slowly.

Late Complications

One major late complication is chronic lymphedema, which occurs in about

30% of patients (29–31,130–132). Recurrent lymphangitis or cellulitis of the leg

develops in about 10% of patients and usually responds to oral antibiotics. The

GROINSS-V study, prospectively following 403 patients and 623 groin

evaluations, reports lymphedema in 25% of patients undergoing complete

inguinofemoral lymphedema and 2% of patients undergoing the sentinel lymph

node procedure with respective recurrent erysipela rates of 16% and 0.4% (122).

Urinary stress incontinence, with or without genital prolapse, occurs in about 10%

of patients after radical vulvectomy and may require corrective surgery. Introital

stenosis can lead to dyspareunia and may require a vertical relaxing incision,

which is sutured transversely. An uncommon late complication is femoral hernia,

which can be prevented intraoperatively by closure of the femoral canal with a

suture from the inguinal ligament to Cooper’s ligament. Pubic osteomyelitis and

rectovaginal or rectoperineal fistulas are rare late complications.

Other major long-term treatment complications associated with the extent

of vulvar surgery include depression, altered body image, and sexual

dysfunction (95,96). Modifications in the radical extent of the surgical approach

and appropriate preoperative and postoperative counseling may help lessen some

of the psychological trauma.

Role of Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy traditionally had a limited role in the management of patients

with vulvar cancer. In the orthovoltage era, local tissue tolerance was poor and

vulvar necrosis was common, but with megavoltage therapy, tolerance improved

significantly. Radiation therapy, frequently with concurrent chemotherapy, has an

increasingly important role in the management of patients with vulvar cancer. It is

important to remember that, with a rare exception, radiation therapy alone has

little place in the primary management of vulvar cancer. It is primarily indicated

2721in conjunction with surgery.

The indications for radiation therapy for patients with primary vulvar cancer

are evolving. Radiation is indicated in the following situations:

1. Preoperative chemoradiation in patients with advanced disease who would

otherwise require pelvic exenteration or suffer loss of anal or urethral

sphincteric function.

2. Preoperative chemoradiation in patients with fixed, unresectable groin nodes.

3. Postoperatively, to treat the pelvic lymph nodes and groins of patients with

multiple microscopically positive groin nodes, one or more macrometastasis

(10 mm or larger), or any evidence of extracapsular spread.

Possible indications for radiation therapy to the vulva include the following:

1. Postoperatively, to help prevent local recurrences in patients with involved (or

close) surgical margins. Radiation to the primary tumor bed following

resection with involved margins may improve 5-year overall survival to 67%,

which is comparable to that of patients with negative margins (133,134).

2. As primary therapy for patients with small primary tumors, particularly clitoral

or periclitoral lesions in young and middle-aged women, for whom surgical

resection would have significant psychological consequences (135).

The benefit to adjuvant radiation therapy in patients with a single groin

micrometastasis is unclear. While the prognosis appears somewhat worse for

this group of patients compared with node negative patients (126,136), there is

little evidence of benefit to adjuvant radiation therapy (54,136,137). Thus, no

additional treatment and careful observation is an option if one microscopically

positive groin node (5 mm or less tumor deposit) is found in a fully dissected

groin. For patients with a single groin node metastasis, a retrospective SEER

database review suggests that adjuvant radiation may provide a therapeutic

benefit, especially if the groin dissection was limited (138). However, size and

characteristics of the nodal metastasis were not known. If unilateral groin

dissection was performed for a lateral lesion, there seems to be no indication for

dissection of the other side, because contralateral lymph node involvement is

likely only if there are multiple microscopic or any gross ipsilateral inguinal node

metastases (54,57). If clinically evident groin metastases, any extracapsular

spread, or two or more microscopically positive groin nodes are found, the

patient is at increased risk of groin and pelvic recurrence and should receive

postoperative groin and pelvic irradiation. In 1977, the GOG initiated a

prospective trial in which patients with positive groin nodes were randomized to

either ipsilateral pelvic node dissection or bilateral pelvic plus groin irradiation

2722(57). The survival rate for the radiation group (68% at 2 years) was significantly

better than the survival rate for the pelvic lymphadenectomy group (54% at 2

years) (p = 0.03). The survival advantage was limited to patients with clinically

evident groin nodes or more than one microscopically positive groin node. Groin

recurrence occurred in 3 of 59 patients (5%) treated with radiation, compared with

13 of 55 (23.6%) patients treated with lymphadenectomy (p = 0.02). Four patients

who received radiation had a pelvic recurrence, compared with one who had

lymphadenectomy. These data highlight the value of groin irradiation in

preventing groin recurrence in patients with multiple positive groin nodes. This

concept of adjuvant radiation therapy including bilateral groins and pelvis for

patients with two or more positive nodes is further supported by the contemporary

AGO-CaRE-1 study demonstrating better outcomes with this adjuvant treatment

approach (136).

Recurrent Vulvar Cancer

Recurrence of vulvar cancer correlates closely with the number of positive groin

nodes (54). Patients with fewer than three positive nodes, particularly if the nodes

are only microscopically involved, have a lower incidence of recurrence at any

site, whereas patients with three or more positive nodes have a high incidence of

local, regional, and systemic recurrences (54,57).

Most recurrences of vulvar cancer occur within the first 2 years from

initial therapy, with groin recurrences occurring sooner (median time to

recurrence 6 to 7 months) than vulvar recurrences (median time to

recurrence 3 years) (69,139–141). About one-third of vulvar cancer relapses

present 5 or more years after initial therapy (69). In a long-term follow-up

study at the Mayo Clinic, nearly 1 in 10 patients with vulvar cancer had a late

(longer than 5 years) reoccurrence of disease (69). More than 95% of those late

relapses had local reoccurrences (same site recurrence or second primary vulvar

site). Because of this propensity for late local reoccurrence, regular and long-term

careful examinations of the vulva and groin constitute the cornerstone of

posttreatment surveillance for these patients.

The published literature on the management and outcome of recurrent disease

is limited. The timing and primary site of recurrence is critical to the prognosis

postrecurrence. Although groin recurrences tend to occur early and are nearly

always fatal, 5-year overall survival rates of 50% to 70% are reported for patients

with surgically treated isolated vulvar recurrences and more than 60% of patients

with local recurrence or reoccurrence were alive at 20 years in the Mayo Clinic

long-term follow-up study (69,141,142). In contrast, a series of 502 patients

demonstrate the poor prognosis for patients with groin, pelvic, or distant

recurrences: 5-year survival rates of 27% with inguinal or pelvic recurrence, 15%

2723with distant recurrence, and 14% with multiple sites of recurrence (143).

Management of recurrent vulvar cancer depends on site of recurrence, prior

treatments, and patient performance status.

Local Vulvar Recurrence

Margin status at the time of radical resection of the vulvar cancer is the most

powerful predictor of local vulvar recurrence, with an almost 50%

recurrence risk with margins closer than 0.8 cm (81). Margin status does not

predict survival (68). Local vulvar recurrences are more likely in patients with

primary lesions larger than 4 cm in diameter, especially if lymph–vascular space

invasion is present, and in patients with deeply invasive tumors (133,144,145).

When detected early, isolated local failure is usually treatable by additional

surgical therapy, often with a myocutaneous graft to cover the defect

(31,38,46,75,146). Radiation therapy, particularly a combination of external beam

therapy plus interstitial needles, frequently combined with chemotherapy, is used

to treat vulvar recurrences (147).

Three distinct patterns of local recurrence are described: remote vulvar

recurrence (greater than 2 cm from the primary tumor site), primary tumor site

recurrence (within 2 cm of the primary tumor site), and skin bridge recurrence

(78,145). Although reported treatment outcomes are excellent for remote site

recurrences with 3-year survival rates of 67% to 100%, the literature is

controversial as to the prognostic significance of primary tumor site recurrences,

with one study reporting a 3-year survival rate of only 15% and the other a 5-year

survival of 93% (78,145). Patients with skin bridge recurrence have a very poor

prognosis, similar to those with groin recurrence.

Regional Inguinal and Distant Recurrence

Regional and distant recurrences are difficult to manage and are associated

with a poor prognosis (133,139,140). Radiation therapy may be used in

conjunction with surgery for groin recurrence, and chemotherapeutic agents that

have activity against squamous carcinomas may be offered for distant metastases.

The literature on the use of chemotherapy for recurrent vulvar cancer consists

mainly of small series. The most extensively studied regimens contain bleomycin,

methotrexate, and lomustine (a nitrosourea); bleomycin and mitomycin C; or

cisplatin, vinorelbine, and paclitaxel, but response rates are low and the duration

of response is usually disappointing (148–152). Extrapolating from data for the

management of recurrent cervical cancer, many experts recommend the

administration of platinum/taxane-based chemotherapy with or without

bevacizumab. There is a role for palliative radiation of select symptomatic

recurrences. Long-term survival is very uncommon with regional or distant

2724recurrence. Symptom control and quality of life are important treatment goals,

and early involvement of a multidisciplinary palliative care team is generally

indicated.

MELANOMA

Vulvar melanomas are rare, with an incidence of 0.1 to 0.19 per 100,000

women (153,154). They account for approximately 10% of all cases and are

the second most common form of vulvar malignancy. Most melanomas arise

de novo, but they may arise from a preexisting junctional nevus. Vulvar

melanomas occur most frequently in postmenopausal white women, but are

commonly seen in individuals with darker pigmented skin. Contrary to cutaneous

melanoma, based on SEER data, there are low racial differences in vulvar

melanomas, the development of which appears to be determined by factors other

than ultraviolet radiation exposure and the photoprotective effects of melanin seen

in cutaneous melanoma (155). The incidence of cutaneous melanomas worldwide

is increasing significantly, but not that of vulvar melanoma (155). Vulvar

melanomas appear to behave in a manner similar to that of other truncal

cutaneous melanomas. From a molecular genetic perspective, vulvar melanoma

more closely resembles acral lentiginous melanoma rather than cutaneous

melanoma. KIT is the most commonly mutated gene detected in up to 35% of

vulvar melanomas. More rarely NRAS and BRAF mutations have been described

(156).

FIGURE 40-6 Melanoma of the vulva involving the right labium minus. (From Hacker

NF, Eifel PJ. Vulvar cancer. In: Berek JS, Hacker NF. Berek & Hacker’s Gynecologic

Oncology. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2015:595.)

Most patients with vulvar melanoma have no symptoms other than a

pigmented lesion that may be enlarging. The lesion may present as macules,

papules, or nodules of irregular configuration and coloration, typically greater

than 7 mm in diameter. Some patients have pruritus or bleeding, a few have a

groin mass, and some lesions are amelanotic. Vulvar melanomas occur most

frequently on the labia majora, followed by the labia minora and the clitoris (157)

(Fig. 40-6); extension into the urethra or vagina at discovery is not uncommon.

Any pigmented lesion on the vulva should be excised or, if the lesion is large,

sampled for biopsy unless it is known to have been present and unchanged for

some years. Most vulvar nevi are junctional and may be precursor lesions to

melanoma; any nevus of the vulva should be removed. Excisional biopsy, rather

than a shave, wedge, or punch biopsy, is recommended to ensure evaluation

of the entire lesion and facilitate microstaging and measurement of tumor

thickness.

Histopathology

2726There are three basic histologic types of vulvar melanoma (158; Fig. 40-7):

1. The mucosal lentiginous melanoma (25% to 57%) is a flat freckle that may

become quite extensive but tends to remain superficial.

2. The nodular melanoma (22% to 28%), which is the most aggressive, is

characterized by a raised lesion that penetrates deeply and may metastasize

widely.

3. The superficial spreading melanoma (4% to 56%) tends to remain relatively

superficial early in its development.

In one of the larger reported series, more than one-fourth of the cases of

melanomas were macroscopically amelanotic (153). Vulvar melanoma tends to

spread early, lymphatically and hematogenously.

Staging

The FIGO staging used for squamous lesions is not applicable to melanomas

because the lesions are usually much smaller and the prognosis is related to

tumor thickness rather than to the diameter of the lesion. The vulvar skin

lacks a well-defined papillary dermis. Breslow measured the thickest portion of

the melanoma from the surface of intact epithelium to the deepest point of

invasion (159). It is important to recognize that tumor thickness and lymph node

status are the primary determinants of survival. The AJCC staging guidelines

for cutaneous melanoma (160) should be used for vulvar melanoma.

Validation studies of staging systems for vulvar melanoma have confirmed that

survival is best predicted by the AJCC staging system (161,162). The AJCC

staging system for cutaneous melanoma is shown in Table 40-7.

The revised 2017 eighth edition of the AJCC staging for cutaneous melanoma

reflects that tumor thickness remains the primary determinant of the T staging in

addition to the presence of ulcerations (160). The mitotic rate is no longer a

staging criterion for T1 tumors, but it remains an important prognostic factor and

should be recorded for all patients with a T1 to T4 primary melanoma lesion.

Specific immunohistochemistry criteria for the detection of micrometastases are

included. Regional lymph node involvement is classified as either clinically

occult (found microscopically, usually based upon a sentinel lymph node biopsy)

or clinically detected (on physical examination or by imaging) without associated

specific size criteria. Microsatellites, satellites, and in-transit cutaneous and/or

subcutaneous metastases are included to stratify the lymph node staging. The

site(s) of distant metastatic disease as stratified by serum lactate dehydrogenase

levels remain part of the staging.

FIGURE 40-7 Vulvar melanoma. Spindle-shaped melanoma cells form interlacing

bundles, and some contain melanin pigment (right upper corner). Epidermal invasion is

evident in the form of Pagetoid migration (left upper corner).

Treatment

Vulvar melanomas are rare and there is minimal data specific to the treatment of

vulvar melanoma. With better understanding of the prognostic significance of the

microstage, some individualization of treatment developed. When feasible, the

primary treatment modality for vulvar melanoma is excision. It is accepted that

lesions with less than 1 mm of invasion may be treated with radical local

excision alone. With more invasive lesions, radical vulvectomy with bilateral

inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy has historically been the recommended

treatment (163). Extrapolating from cutaneous melanoma and supported by

smaller case series of the vulva, it has become apparent that most failures are

distant and radical vulvectomy does not appear to enhance survival. Based on this

recognition, the contemporary more conservative surgical approach evolved,

where surgery for vulvar melanoma entails a radical local excision with

sentinel lymph node biopsy in clinically node negative patients, followed by

2728complete inguinofemoral lymphadenectomy for those with involved sentinel

lymph nodes. Skin margins for melanomas <1 mm thick should be 1 cm; if

anatomically feasible, margins should be extended to 2 cm for melanomas with

≥1 mm thickness. At least a 1-cm tumor-free deep surgical margin down to the

fascia is recommended, irrespective of tumor thickness. This conservative

surgical approach is further supported by a SEER data analysis of 644 patients

with vulvar melanoma which did not find a survival difference in patients with

localized disease treated with more conservative versus radical surgery. Five-year

disease-specific survival rates for patients undergoing conservative surgery for

localized disease were 75% versus 79% for those undergoing radical surgery

(164). Because melanomas commonly involve the clitoris and labia minora, the

vaginourethral margin of resection is a common site of failure, and care should be

taken to obtain an adequate “inner” resection margin (165). A 10-year survival

rate of 61% was shown for lateral lesions, compared with 37% for medial lesions

(p = 0.027) (144). In locally advanced cases, primary exenteration should not be

routinely offered because of the high risk of distant failure. In these cases,

radiation therapy with or without immunotherapy may be a preferred

consideration.

Controversy exists as to which patients may benefit from inguinal–femoral

lymphadenectomy. A prospective study by the GOG demonstrated that the risk

of inguinal–femoral lymph node metastasis correlated with the Breslow

microstage (166). As with cutaneous melanoma, it appears that for superficial

lesions (tumor thickness <1 mm), the risk for nodal spread is so low that routine

lymphadenectomy is not indicated as long as the nodes appear clinically free of

disease. For intermediate-thickness (1 to 4 mm) cutaneous melanoma, a

randomized controlled trial of elective lymph node dissection versus observation

showed a 5-year survival advantage for patients who underwent elective lymph

node dissection, who were younger than 60 years, and whose tumors were

characterized by 1- to 2-mm thickness and no ulcerations (167). Patients with

deeply invasive cutaneous melanomas (≥4 mm tumor thickness) have a high risk

of regional and systemic metastases and were noted to be unlikely to benefit from

regional lymphadenectomy (168). A randomized controlled trial evaluated 2,001

patients with intermediate thickness cutaneous melanoma and clinically negative

nodes who underwent either nodal observation with lymphadenectomy for local

relapse or sentinel node biopsy with immediate complete lymphadenectomy for

those with positive sentinel nodes. Significantly improved melanoma-specific 10-

year survival rates were observed in the sentinel node assessment group (169).

Specific to patients with vulvar melanoma, there is a small body of literature to

suggest that there may be a clinical benefit in elective groin lymphadenectomy

and the resection of clinically positive nodes (170,171). Studies on the sentinel

2729lymph node procedure specific to vulvar melanoma are limited. Although the

sentinel node procedure appears appropriate for select patients with vulvar

melanoma, the importance of an expert team familiar with the procedure and

consisting of a gynecologic oncologist, a nuclear medicine specialist, and a

pathologist with expertise in microstaging cannot be overemphasized. The

prognosis for patients with positive pelvic nodes is so poor that there seems to be

no value in performing pelvic lymphadenectomy for this disease.

Table 40-7 Eighth (2017) Edition AJCC Melanoma TNM Definitions and Staging

(161)

Primary Tumor

Tx Primary tumor thickness cannot be assessed

T0 No evidence of primary tumor

Tis Melanoma in situ

T1 ≤1 mm thickness

T1a a: <0.8 mm and without ulceration

T1b b: 0.8–1 mm or with ulceration

T2 >1 to 2 mm thickness

T2a a: without ulceration

T2b b: with ulceration

T3 >2 to 4 mm thickness

T3a a: without ulceration

T3b b: with ulceration

T4 >4 mm thickness

T4a a: without ulceration

T4b b: with ulceration

Regional Lymph Nodes

NX Regional nodes not assessed

2730N0 No regional metastases detected

N1 One tumor-involved node or in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite

metastases with no tumor-involved nodes

N1a a: one clinically occult (i.e., detected by SLN biopsy)

N1b b: one clinically detected (on examination or imaging)

N1c c: in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases with no tumorinvolved nodes

N2 Two or three tumor-involved nodes or in-transit, satellite, and/or

microsatellite metastases with one tumor-involved node

N2a a: two or three clinically occult (i.e., detected by SLN biopsy)

N2b b: two or three positive, at least one clinically detected

N2c c: in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases with one tumorinvolved node (occult or clinically detected)

N3 Four or more tumor-involved nodes or in-transit, satellite, and/or

microsatellite metastases with two or more tumor-involved nodes, or

any number of matted nodes without or with in-transit, satellite, and/or

microsatellite metastases

N3a a: four or more clinically occult (i.e., detected by SLN biopsy)

N3b b: four or more, at least one clinically detected, or any number of matted

nodes

N3c c: in-transit, satellite, and/or microsatellite metastases with two or more

tumor-involved nodes (occult or clinically detected) or any matted

nodes

Distant Metastases

M0 No evidence of distant metastasis

M1 Evidence of distant metastasis

M1a a: Distant metastasis to skin, soft tissue including muscle, and/or

nonregional lymph node

M1a(0) a(0): LDH not elevated

2731M1a(1) a(1): LDH elevated

M1b b: Distant metastasis to lung with or without M1a sites of disease

M1b(0) b(0): LDH not elevated

M1b(1) b(1): LDH elevated

M1c c: Distant metastasis to non-CNS visceral sites with or without M1a or

M1b sites of disease

M1c(0) c(0): LDH not elevated

M1c(1) c(1): LDH elevated

M1d d: Distant metastasis to CNS with or without M1a, M1b, or M1c sites of

disease

M1d(0) d(0): LDH not elevated

M1d(1) d(1): LDH elevated

Stage

0 Tis, N0, M0

IA T1a, N0, M0

IB T1b or T2a, N0, M0

IIA T2b or T3a, N0, M0

IIB T3b or T4a, N0, M0