Chapter 10. Prenatal Care

BS. Nguyễn Hồng Anh

Te American Academy o Pediatrics and the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2017) dene prenatal care as “A comprehensive antepartum program involves a coordinated approach to medical care, continuous risk assessment, and psychosocial support that optimally begins beore pregnancy and extends throughout the postpartum and interpregnancy period.” As promulgated by John Ballantyne, such care has been a bedrock to improve pregnancy outcomes or more than 100 years (Reiss, 2000).

PRENATAL CARE IN THE UNITED STATES

Almost a century ater its introduction, prenatal care has become one o the most requently used health services in the United States. According to the Centers or Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), only 1.6 percent o women who gave birth in 2016 received no prenatal care (Osterman, 2018). Arican-American and Hispanic women have high rates o inadequate or no prenatal care that reach 10 and 7.7 percent, respectively. Tis gure is greater or adolescents, particularly those younger than 15 years compared with older age groups. Tese data highlight areas o potential improvement by the health-care system.

■ Prenatal Care Effectiveness

Care designed during the early 1900s ocused on lowering the extremely high maternal mortality rate. Prenatal care undoubtedly contributed to the dramatic decline in maternal deaths rom 690 per 100,000 births in 1920 to 50 per 100,000 by 1955 (Loudon, 1992). Data rom 1998 to 2005 rom the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System identied a veold increased risk or maternal death in women who received no prenatal care (Berg, 2010).

Goldenberg and McClure (2018) have emphasized the importance o prenatal care to reduce stillbirth rates as well. In a study o almost 29 million births, the risk or preterm birth, stillbirth, early and late neonatal death, and inant death rose linearly with decreasing prenatal care utilization (Partridge, 2012). Similarly, rom Parkland Hospital, Leveno and associates (2009) ound that a signicant decline in preterm births correlated closely with any use o prenatal care by medically indigent women. And in women with diabetes, adherence to prenatal care resulted in lower rates o neonatal admissions to the intensive care unit (Sperling, 2018a). Group prenatal care is acceptable and eective (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2018g). Ickovics and coworkers (2016) compared this with individual prenatal care. Group care provided traditional pregnancy surveillance in a group setting with special ocus on support, education, and active health-care participation. Women enrolled in group care had signicantly better pregnancy outcomes. Carter and colleagues (2017) cited similar results. Childbirth education classes are also reported to result in better pregnancy outcomes (Ashar, 2017). Pregnancy in adolescents carries special risk, and guidelines have been developed that ocus on this age group (Fleming, 2015).

DIAGNOSIS OF PREGNANCY

Pregnancy is usually identied when a woman presents with symptoms and possibly a positive home urine pregnancy test result. ypically, these women receive conrmatory testing o urine or blood or human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG). Further, presumptive signs or diagnostic ndings o pregnancy may be ound during the clinical examination. Sonography is oten used, especially i miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy is a concern.

■ Symptoms and Signs

Amenorrhea in a healthy reproductive-aged woman who previously has experienced spontaneous, cyclical, predictable menses is highly suggestive o pregnancy. Menstrual cycles vary appreciably in length among women and even in the same woman (Chap. 5, p. 83). Tus, amenorrhea is not a reliable pregnancy indicator until 10 or more days have passed ater expected menses. Occasionally, uterine bleeding that mimics menstruation is noted ater conception. During the rst month o pregnancy, these episodes are likely the consequence o blastocyst implantation. Still, rst-trimester bleeding should prompt evaluation or an abnormal pregnancy.

O other symptoms, maternal perception o etal movement depends on actors such as parity and habitus. In general, ater a rst successul pregnancy, a woman may rst perceive etal movements between 16 and 18 weeks’ gestation. A primigravida may not appreciate etal movements until approximately 2 weeks later. At about 20 weeks, depending on maternal habitus, an examiner can begin to detect etal movements. O pregnancy signs, changes in the lower reproductive tract, uterus, and breasts develop early.

■ Pregnancy Tests

Detection o hCG in maternal blood and urine is the basis or endocrine assays o pregnancy. Syncytiotrophoblast produces hCG in amounts that increase exponentially during the rst trimester. hCG and luteinizing hormone (LH) share the same receptor in tissues. Tus, a main unction o hCG is to prevent involution o the corpus luteum, which is the principal site o progesterone ormation during the rst 6 weeks o pregnancy.

With a sensitive test, the hormone can be detected in maternal serum or urine by 8 to 9 days ater ovulation. Te doubling time o serum hCG concentration is 1.4 to 2.0 days. As shown in Figure 10-1, serum levels range widely and increase rom the day o implantation. Lower levels o hCG rise more rapidly than higher levels (Barnhart, 2016). Peak hCG levels are reached at 60 to 70 days. Tereater, the concentration declines slowly to a plateau at approximately 16 weeks’ gestation.

Measurement of hCG

Tis hormone is a glycoprotein with high carbohydrate content. Te general structure o hCG is a heterodimer composed o two dissimilar subunits, designated α and β, which are noncovalently linked. Te α-subunit is identical to those o LH, ollicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and thyroid-stimulating hormone (SH), but the β-subunit is structurally distinct. Tus, antibodies were developed with high specicity or the hCG β-subunit. Tis specicity allows its detection, and numerous commercial immunoassays are available or measuring serum and urine hCG levels. Each immunoassay detects a slightly dierent mixture o hCG variants, its ree subunits, or its metabolites—however, all are appropriate or pregnancy testing (Braunstein, 2014). Depending on the assay used, the sensitivity or the laboratory detection limit o hCG in serum is 1.0 mIU/mL or even lower.

False-positive hCG test results are rare. A ew women have circulating serum actors that may bind erroneously with the test antibody directed to hCG in a given assay. Te most common actors are heterophilic antibodies. Tese are produced by an individual and bind to the animal-derived test antibodies used in a given immunoassay. Tus, women who have worked closely with animals are more likely to develop these antibodies, and alternative laboratory techniques are available (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017a). Elevated hCG levels may also reect molar pregnancy and its associated neoplasms (Chap. 13, p. 238). Other rare causes o positive assays without pregnancy are (1) exogenous hCG injection used or weight loss, (2) renal ailure with impaired hCG clearance, (3) physiological pituitary hCG, and (4) hCG-producing tumors that most commonly originate rom gastrointestinal sites, ovary, bladder, or lung (McCash, 2017).

Home Pregnancy Tests

More than 60 dierent types o over-the-counter pregnancy test kits are available in the United States (Grenache, 2015). Unortunately, many o these are not as accurate as advertised (Johnson, 2015). For example, Cole and associates (2011) ound that a detection limit o 12.5 mIU/mL would be required to diagnose

FIGURE 10-1 Mean concentration (95% CI) of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) in serum of women throughout normal pregnancy.

95 percent o pregnancies at the time o missed menses. However, they reported that only one brand had this degree o sensitivity. wo other brands gave alse-positive or invalid results. In act, with an hCG concentration o 100 mIU/mL, clearly positive results were displayed by only 44 percent o brands. Accordingly, only approximately 15 percent o pregnancies could be diagnosed at the time o the missed menses. Some manuacturers o even newer home urine assays claim >99-percent accuracy or tests done on the day o—and some up to 4 days beore—the expected day o menses. Again, careul analysis suggests that these assays are oten not as sensitive as advertised.

■ Sonographic Recognition of Pregnancy

ransvaginal sonography is commonly used to accurately establish gestational age and conrm pregnancy location. A gestational sac is the rst sonographic evidence o pregnancy, and it may be seen with transvaginal sonography by 4 to 5 weeks’ gestation. It should not be conused with a pseudogestational sac.

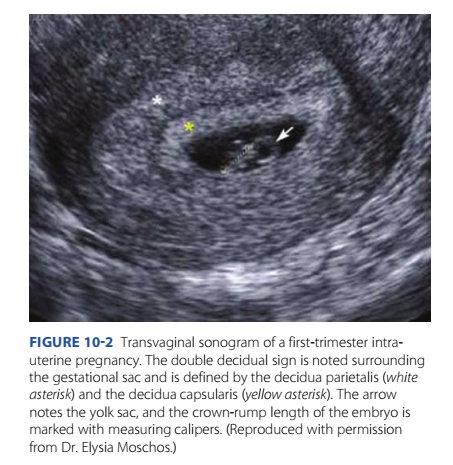

Te latter, or pseudosac, is a uid collection within the endometrial cavity, which can occur in the setting o ectopic pregnancy (Fig. 12-3, p. 223). Further evaluation may be warranted i this is the only sonographic nding, particularly in a woman with pain or bleeding. A normal gestational sac implants eccentrically in the endometrium, whereas a pseudosac is seen in the midline o the endometrial cavity. Other potential indicators o early intrauterine pregnancy are an anechoic center surrounded by a single echogenic rim—the intradecidual sign—or two concentric echogenic rings surrounding the gestational sac—the double decidual sign (Fig. 10-2). I sonography yields equivocal ndings, the term pregnancy o unknown location (PUL) is applied (Bobdiwala, 2019). In these cases, serial serum hCG levels and transvaginal sonography can help dierentiate a normal intrauterine pregnancy rom an extrauterine pregnancy or an early miscarriage (Chap. 12, p. 222).

I the yolk sac—a brightly echogenic ring with an anechoic center—is seen within the gestational sac, an intrauterine location or the pregnancy is conrmed. Te yolk sac can normally be seen by the middle o the th week. As shown in Figure 10-2, ater 6 weeks, an embryo is seen as a linear structure immediately adjacent to the yolk sac. Cardiac motion is typically noted at this point.

INITIAL PRENATAL EVALUATION

Prenatal care is ideally initiated early. Major goals are to (1) dene the health status o the mother and etus, (2) estimate the gestational age, and (3) initiate a plan or continued obstetrical care. ypical components o the initial visit are summarized in Table 10-1. Subsequent care may range rom relatively inrequent routine visits to prompt hospitalization because o serious maternal or etal disease.

■ Prenatal Record

Use o a standardized record within a perinatal health-care system greatly aids antepartum and intrapartum management. Standardizing documentation allows communication and care continuity between providers and enables objective measures o care quality to be evaluated over time and across dierent clinical settings (Gregory, 2006). A prototype is provided by the American Academy o Pediatrics and the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2017) in their Guidelines or Perinatal Care, 8th edition.

Definitions

Several denitions are pertinent to establishment o an accurate prenatal record.

1. Nulligravida—a woman who currently is not pregnant and has never been pregnant.

2. Gravida—a woman who currently is pregnant or has been in the past, irrespective o the pregnancy outcome. With the establishment o the rst pregnancy, she becomes a primigravida, and with successive pregnancies, a multigravida.

3. Nullipara—a woman who has never completed a pregnancy beyond 20 weeks’ gestation. She may not have been pregnant or may have had a spontaneous or elective abortion(s) or an ectopic pregnancy.

4. Primipara—a woman who has been delivered only once o

a etus or etuses born alive or dead with an estimated gestation duration o 20 or more weeks. In the past, a 500-g birthweight threshold was used to dene parity. Tis threshold is now controversial. Namely, many states still use this weight to dierentiate a stillborn etus rom an abortus, but the survival o neonates with birthweights <500 g is no longer uncommon (Chap. 1, p. 2).

5. Multipara—a woman who has completed two or more pregnancies with gestational ages at least 20 weeks. Parity is determined by the number o pregnancies reaching 20 weeks. It is not increased to a higher number i multiples are delivered in a given pregnancy. Moreover, stillbirth does not lower this number.

FIGURE 10-2 Transvaginal sonogram of a first-trimester intrauterine pregnancy. The double decidual sign is noted surrounding the gestational sac and is defined by the decidua parietalis (white asterisk) and the decidua capsularis (yellow asterisk). The arrow notes the yolk sac, and the crown-rump length of the embryo is marked with measuring calipers. (Reproduced with permission from Dr. Elysia Moschos.)

TABLE 10-1. Typical Components of Routine Prenatal Care

In some locales, the obstetrical history is summarized by a series o digits connected by dashes. Tese reer to the number o term newborns, preterm neonates, abortuses younger than 20 weeks, and children currently alive. For example, a woman who is para 2–1–0–3 has had two term deliveries, one preterm delivery, no abortuses, and has three living children. Because these are nonconventional, it is helpul to speciy the outcome o any pregnancy that did not end normally.

Normal Pregnancy Duration

Te normal duration o pregnancy calculated rom the rst day o the last normal menstrual period is very close to 280 days or 40 weeks. A quick estimate o a pregnancy due date based on menstrual data can be made as ollows: add 7 days to the rst day o the last period and subtract 3 months. For example, i the rst day o the last menses was October 5, the due date is 10-05 minus 3 (months) plus 7 (days) = 7–12 or July 12 o the ollowing year. Tis calculation is the Naegele rule. However, menstrual cycle length varies among women and renders many o these calculations inaccurate. Tis, combined with the requent use o rst-trimester sonography, has changed the method o determining an accurate gestational age. Te American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2017e), the American Institute o Ultrasound in Medicine, and the Society or Maternal-Fetal Medicine have emphasized that rst-trimester ultrasound is the most accurate method to establish or reafrm gestational age. For pregnancies conceived by assisted reproductive technologies, embryo age or transer date is used to assign gestational age. I available, the gestational ages calculated rom the last menstrual period and rom rst-trimester ultrasound are compared, and this estimated date o delivery is recorded. Reconciling any discordance between these two values is discussed in Chapter 14 (p. 248).

Trimesters

It has become customary to divide pregnancy into three equal epochs or trimesters o approximately 3 calendar months. More recently a “ourth trimester” has been recognized to emphasize the need or comprehensive postpartum care (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2018i). Tis is discussed in Chapter 36 (p. 634). Historically, the rst trimester extends through completion o 14 weeks, the second through 28 weeks, and the third through 42 weeks. Te ourth is the 12 weeks ater delivery. Tus, prenatally, there are three periods o 14 weeks each. Certain major obstetrical problems tend to cluster in each o these three time periods. For example, most spontaneous abortions take place during the rst trimester, whereas most women with hypertensive disorders due to pregnancy are diagnosed during the third trimester. In modern obstetrics, the clinical use o trimesters to describe a specic pregnancy is imprecise. For example, it is inappropriate in cases o uterine hemorrhage to categorize the problem temporally as “third-trimester bleeding.” Appropriate management or the mother and her etus will vary remarkably depending on whether bleeding begins early or late in the third trimester (Chap. 42, p. 733). Because precise knowledge o etal age is imperative or obstetrical management, the clinically appropriate unit is weeks o gestation completed. Clinicians designate gestational age using completed weeks and days. For example, 334/7 weeks or 33 + 4 describes pregnancy duration o 33 completed weeks and 4 days.

Previous and Current Health Status

As elsewhere in medicine, history-taking begins with queries concerning medical or surgical disorders. Detailed inormation regarding previous pregnancies is essential, as many obstetrical complications tend to recur in subsequent pregnancies. Te menstrual and contraceptive histories also are important. As noted earlier, gestational age may be less accurate or those with irregular menses. Moreover, some methods o birth control avor ectopic implantation ollowing method ailure (Chap. 38, p. 665).

Psychosocial Screening. Te American Academy o Pediatrics and the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2017) dene psychosocial issues as nonbiomedical actors that aect mental and physical well-being. Women should be screened regardless o social status, education level, race, or ethnicity. Such screening should seek barriers to care, communication obstacles, nutritional status, unstable housing, desire or pregnancy, saety concerns that include intimate-partner violence, depression, stress, and use o substances such as tobacco, alcohol, and illicit drugs. Tis screening is perormed on a regular basis, at least once per trimester, to identiy important issues and reduce adverse pregnancy outcomes. Coker and colleagues (2012) compared pregnancy outcomes in women beore and ater implementation o a universal psychosocial screening program and ound that screened women were less likely to have preterm or low-birthweight newborns, as well as other adverse outcomes. Specic screens or depression are presented in Chapter 64 (p. 1143). Cigarette Smoking. Tese data are included on the birth certi- icate, and the number o pregnant women who smoke continues to decline. From 2000 to 2010, the prevalences were 12 to 13 percent (ong, 2013). By 2016, the incidence was 7.2 percent according to the National Center or Health Statistics (Drake, 2018). Concurrent with the decline in cigarette use, there has been an increase in electronic cigarettes/vaping with a reported prevalence o 0.6 to 15 percent (Whittington, 2018). In a survey o more than 3000 mothers in Oklahoma and exas, 7 percent reported using electronic vapor products prior to conception and in the postpartum period. O these women, according to the CDC, 1.4 percent used them during the last 3 months o pregnancy (Kapaya, 2019).

According to the American Society or Reproductive Medicine (2018), smoking is associated with subertility. Higher rates o miscarriage, stillbirth, low birthweight, and preterm delivery also are linked to smoking during pregnancy (Dahlin, 2016; Luke, 2018; ong, 2013). Compared with nonsmokers, risks o placenta previa, placental abruption, and premature membrane rupture are increased twoold. Potential teratogenic eects are reviewed in Chapter 8 (p. 156). Tus, the U.S. Preventive Services ask Force recommends that clinicians oer counseling and eective intervention options to pregnant smokers at the rst and subsequent prenatal visits (Siu, 2015). Although benets are greatest i smoking ceases early in pregnancy or preerably preconceptionally, quitting at any stage o pregnancy can improve perinatal outcomes (Soneji, 2019). Compared with simple counseling to quit, person-to-person psychosocial interventions are signicantly more successul in achieving smoking abstinence in pregnancy (Fiore, 2008). One example is a brie counseling session covering the “5As” o smoking cessation (Table 10-2). Tis approach can be accomplished in 15 minutes or less and is eective when initiated by health-care providers (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2020b).

Behavioral interventions and nicotine replacement products are successul in reducing smoking rates (Patnode, 2015). However, nicotine replacement has not been sufciently evaluated to determine its eectiveness and saety in pregnancy. rials evaluating such therapy have yielded conicting evidence (Coleman, 2015; Spindel, 2016). wo randomized trials also produced inconclusive results. In the Smoking and Nicotine in Pregnancy (SNAP) trial, Cooper and associates (2014) reported that a temporary cessation o smoking may have been associated with improved inant development. In the Study o Nicotine Patch in Pregnancy (SNIPP) trial, no dierences in smoking cessation rates or birthweights were ound (Berlin, 2014). Similar preliminary results were reported or sustained-release bupropion (Nanovskaya, 2017). Olson and colleagues (2019) reported that nancial incentives were helpul to encourage smoking cessation.

Because o limited available evidence to support pharmacotherapy or smoking cessation in pregnancy, the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2020b) recommends that i nicotine replacement therapy is used, it should be done with close supervision and ater careul consideration o the risks o smoking versus nicotine replacement.

Alcohol. Ethyl alcohol or ethanol is a potent teratogen that causes the etal alcohol spectrum disorders. Fetal alcohol syndrome, the most severe orm o these disorders, is characterized by growth restriction, acial abnormalities, and central nervous system dysunction. Te estimated prevalence o these disorders is 11 to 50 per 1000 (May, 2018).

As discussed in Chapter 8 (p. 150), women who are pregnant or considering pregnancy should abstain rom drinking any alcoholic beverages (Sarman, 2018). Te CDC analyzed data rom the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System rom 2015 to 2017 and estimated that 12 percent o pregnant women used alcohol (Denny, 2019). Te American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2021a) in collaboration with the CDC has developed the Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) Prevention Program, which provides resources or providers and is available at www.acog.org/alcohol.

Illicit Drugs. An estimated 10 percent o etuses are exposed to one or more illicit drugs. Agents may include heroin and other opiates, cocaine, amphetamines, barbiturates, and marijuana (American Academy o Pediatrics, 2017). As discussed in Chapter 8 (p. 157), chronic use o large quantities is harmul to the etus (Metz, 2015). Well-documented sequelae include etal-growth restriction, low birthweight, and drug withdrawal soon ater birth. Adverse eects o marijuana are less convincing. Women who use such drugs requently do not seek prenatal care, which in itsel is associated with risks or preterm and low-birthweight neonates (Eriksen, 2016).

For women who abuse heroin, methadone maintenance can be initiated within a registered methadone treatment program to reduce complications o illicit opioid use and narcotic withdrawal, to encourage prenatal care, and to avoid drug culture risks (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017g). Available programs can be ound through the treatment locator o the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration at www.samhsa.gov. Methadone dosages usually are initiated at 10 to 30 mg orally daily and titrated as needed. In some women, careul methadone taper may be an appropriate option (Stewart, 2013). Buprenorphine alone or in combination with naloxone also may be oered and managed by physicians with specic credentialing. Tese therapeutic options are considered in greater detail in Chapter 64 (p. 1150).

Intimate-Partner Violence. Tis term reers to a pattern o assault and coercive behavior that may include physical injury, psychological abuse, sexual assault, progressive isolation, stalking, deprivation, intimidation, and reproductive coercion (Miller, 2019). Such violence is recognized as a major public health problem. Unortunately, most abused women continue to be victimized during pregnancy. With the possible exception o preeclampsia, intimate-partner violence (IPV) is more prevalent than any major medical condition detectable through routine prenatal screening (American Academy o Pediatrics, 2017). Te estimated prevalence during pregnancy lies between 4 and 8 percent. IPV is associated with an increased risk o several adverse perinatal outcomes that include preterm delivery, etal-growth restriction, and perinatal death (Chap. 50, p. 891).

Te American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2019c) has provided methods or IPV screening and recommends their use at the rst prenatal visit, again at least once per trimester, and again at the postpartum visit. Such screening should be done privately and away rom amily members and riends. Patient sel-administered or computerized screenings appear to be as eective or disclosure as clinician-directed interviews (Ahmad, 2009; Chen, 2007). Physicians should be amiliar with state laws that may require reporting o IPV. Coordination with social services can be invaluable in these cases. Te National Domestic Violence Hotline (1–800–799- SAFE [7233]) is a nonprot telephone reerral service that provides individualized inormation regarding city-specic shelter locations, counseling resources, and legal advocacy.

■ Clinical Evaluation

Torough, general physical and pelvic examinations should be completed at the initial prenatal encounter. Te cervix is visualized using a speculum lubricated with warm water or water-based lubricant gel. Bluish-red passive hyperemia o the cervix is characteristic, but not diagnostic, o pregnancy. Dilated, occluded cervical glands bulging beneath the ectocervical mucosa—nabothian cysts—may be prominent. Te cervix is not normally dilated except at the external os. o identiy cytological abnormalities, a Pap test is perormed according to current guidelines noted in Chapter 66 (p. 1164). Specimens or identication o Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are obtained when indicated (p. 181). Bimanual examination is completed by palpation. Special attention is given to the consistency, length, and dilation o the

TABLE 10-2. Five A’s of Smoking Cessation ASK about smoking at the first and subsequent prenatal visits.

ADVISE with clear, strong statements that explain the risks of continued smoking to the woman, fetus, and newborn.

ASSESS the patient’s willingness to attempt cessation.

ASSIST with pregnancy-specific, self-help smoking cessation materials. Offer a direct referral to the smokers’ quit line (1-800-QUIT NOW) to provide ongoing counseling and support.

ARRANGE to track smoking abstinence progress at subsequent visits.

Adapted from American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2020b; Fiore, 2008.

cervix; to uterine and adnexal size; to the bony pelvic architecture; and to any vaginal or perineal anomalies. Oten, later in pregnancy, etal presentation also can be determined. Lesions o the cervix, vagina, or vulva are urther evaluated as needed by colposcopy, biopsy, or culture. Te perianal region is inspected, and digital rectal examination is perormed as required or complaints o rectal pain, bleeding, or mass.

Gestational Age Assessment

Precise knowledge o gestational age is essential or prenatal care, because several pregnancy complications may develop and optimal treatment will depend on etal age. Menstrual history is best conrmed by rst-trimester sonography (Chap. 14, p. 248). Tat said, gestational age can also be estimated with considerable precision by a careully perormed clinical uterine size examination that is coupled with last menstrual period dating.

Uterine size similar to a small orange roughly correlates with a 6-week gestation; a large orange, with an 8-week pregnancy; and a graperuit, with one at 12 weeks (Margulies, 2001).

■ Laboratory Tests

Recommended routine tests at the rst prenatal encounter are listed in able 10-1. Initial blood tests include a complete blood count, a determination o blood type and Rh status, and an antibody screen. Te Institute o Medicine recommends universal human immunodeciency virus (HIV) testing as a routine part o prenatal care. Tis testing is explained to the patient, who may decline. Te American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2018j) continues to support this practice. I a woman declines, this is recorded in the prenatal record. All pregnant women are screened also or hepatitis B virus inection, syphilis, and immunity to rubella at the initial visit.

Based on their prospective investigation o 1000 women, Murray and coworkers (2002) concluded that in the absence o hypertension, routine urinalysis beyond the rst prenatal visit was unnecessary. A urine culture is recommended by most, because treating bacteriuria signicantly reduces the likelihood o developing symptomatic urinary tract inections in pregnancy (Chap. 56, p. 996).

Cervical Infections

C trachomatis is isolated rom the cervix in 2 to 13 percent o pregnant women. Te American Academy o Pediatrics and the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2017) recommend that all women be screened or chlamydia during the rst prenatal visit, with additional third-trimester testing or those at increased risk. Risk actors include unmarried status, recent change in sexual partner or multiple concurrent partners, age younger than 25 years, inner-city residence, history or presence o other sexually transmitted diseases, and little or no prenatal care. For those testing positive, treatment described in Chapter 68 (p. 1212) is ollowed by a second testing—a test o cure—3 to 4 weeks ater treatment completion.

N gonorrhoeae typically causes cervicitis or urethritis in pregnancy. Inrequently, it may also cause septic arthritis (Bleich, 2012). Risk actors or gonorrhea are similar to those or chlamydial inection. Te American Academy o Pediatrics and the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2017) recommend that pregnant women with risk actors or those living in an area o high N gonorrhoeae prevalence be screened at the initial prenatal visit and again in the third trimester. reatment is given or gonorrhea and simultaneously or possible coexisting chlamydial inection (Chap. 68, p. 1211). est o cure is recommended ollowing treatment.

■ Pregnancy Risk Assessment

Many actors can adversely aect maternal and etal well-being. Some are evident at conception, but many become apparent during the course o pregnancy. Te designation o “high-risk pregnancy” is overly vague or an individual woman and is best avoided i a more specic diagnosis can be assigned. Some common risk actors or which consultation is recommended by the American Academy o Pediatrics and the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2017) are shown in

Table 10-3. Some conditions may require the involvement o a maternal-etal medicine specialist, geneticist, neonatologist, anesthesiologist, cardiologist, or other specialist.

SUBSEQUENT PRENATAL VISITS

Tese are traditionally scheduled at 4-week intervals until 28 weeks, then every 2 weeks until 36 weeks, and weekly thereater. Women with complicated pregnancies—or example, with twins or diabetes—oten require return visits at 1- to 2-week intervals (Power, 2013). In 1986, the Department o Health and Human Services convened an expert panel to review the content o prenatal care. Tis report was subsequently reevaluated and revised in 2005 (Gregory, 2006). Te panel recommended, among other things, early and continuing risk assessment that is patient specic. It also endorsed exibility in clinical visit spacing; health promotion and education, including preconceptional care; medical and psychosocial interventions; standardized documentation; and expanded prenatal care objectives that include amily health up to 1 year ater birth.

Te World Health Organization conducted a multicenter randomized trial with almost 25,000 women that compared routine prenatal care with an experimental model designed to minimize visits (Villar, 2001). In the new model, women were seen once in the rst trimester and screened or certain risks. Tose without anticipated complications—80 percent o those screened—were seen again at 26, 32, and 38 weeks. Compared with routine prenatal care, which required a median o eight visits, the new model required a median o only ve. No disadvantages were attributed to the regimen with ewer visits, and these ndings are consistent with other randomized trials.

■ Prenatal Surveillance

At each return visit, the well-being o mother and etus are assessed (see able 10-1). Fetal heart rate, growth, and activity are evaluated. Maternal blood pressure and weight and their extent o change are assessed. Symptoms such as abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, bleeding, vaginal uid leakage, headache, altered vision, and dysuria are sought. Ater 20 weeks’ gestation, uterine examination measures size rom the symphysis to the undus with a traditional tape measure. In late pregnancy, vaginal examination oten provides valuable inormation. Tis may include conrmation o the presenting part and its station, clinical estimation o pelvic capacity and conguration, etal ballottement as a reection o sufcient amnionic uid volume, and cervical consistency, eacement, and dilation (Chap. 22, p. 426).

Fundal Height

Between 20 and 34 weeks’ gestation, the height o the uterine undus measured in centimeters correlates closely with gestational age in weeks. Tis measurement is used to monitor etal growth and amnionic uid volume. It is measured along the abdominal wall rom the top o the symphysis pubis to the top o the undus. Importantly, the bladder must be emptied beore undal measurement. Obesity or the presence o uterine masses such as leiomyomas also may limit undal height measurement accuracy. Moreover, using undal height alone, etal-growth restriction may be undiagnosed in up to a third o cases (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2021b; Haragan, 2015).

Fetal Heart Sounds

Instruments incorporating Doppler ultrasound are usually used to easily detect etal heart action, and in the absence o maternal obesity, heart sounds are almost always detectable by 10 weeks with such instruments (Chap. 24, p. 447). Te etal heart rate ranges rom 110 to 160 beats per minute and is typically heard as a double sound. Using a standard nonamplied stethoscope, the etal heart is audible by 20 weeks in 80 percent o women, and by 22 weeks, heart sounds are expected to be heard in all (Herbert, 1987). Because the etus moves reely in amnionic uid, the site on the maternal abdomen where etal heart sounds can be heard best will vary.

Additionally, with ultrasonic auscultation, one may hear the unic soue, which is a sharp, whistling sound that is synchronous with the etal pulse. It is caused by the rush o blood through the umbilical arteries and may not be heard consistently. In contrast, the uterine soue is a sot, blowing sound that is synchronous with the maternal pulse. It is produced by the passage o blood through the dilated uterine vessels and is heard most distinctly near the lower portion o the uterus.

Sonography

Ultrasound imaging provides invaluable inormation regarding etal anatomy, growth, and well-being. As such, it is recommended that all pregnant women be oered at least one prenatal sonographic examination (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2018l). Continuing trends suggest that the number o these examinations perormed per pregnancy is increasing. Data rom commercial insurance plans indicate that even low-risk pregnancies receive an average o 4 to 5 ultrasound examinations (O’Keee, 2013). Sonography should be perormed only or valid medical indications. Additionally, needed inormation is obtained using the lowest possible ultrasound exposure settings, which is the as low as reasonably achievable (ALARA) principle (American Institute o Ultrasound in Medicine, 2016).

■ Subsequent Laboratory Tests

I initial results were normal, most tests need not be repeated. Hematocrit or hemoglobin determination, along with serology

TABLE 10-3. Conditions for Which Maternal-Fetal Medicine Consultation May Be Beneficial

Genetic Screening

Serum screening or etal aneuploidy is routinely oered to all pregnant women—in the rst trimester at 10 to 14 weeks, in the second trimester at 15 to 20 weeks, or as cell-ree DNA screening at any point ater 10 weeks (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2020d). Additionally, the College recommends that both cystic brosis carrier screening and screening or spinal muscular atrophy should be oered to all women considering pregnancy or who are currently pregnant, provided that carrier or disease status is not already known (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologist, 2017b).

Historically, carrier screening or selected genetic abnormalities was oered only to women at increased risk based on ethnic or racial background. One example is screening or ay-Sachs disease in those o Ashkenazi Jewish descent. However, given our increasingly diverse, multiethnic society, previous assumptions about carrier risk may no longer apply. Although ethnicityspecic carrier screening remains an option, providers should also consider panethnic and expanded carrier screening strategies (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017c). Tese are discussed urther in Chapter 17 (p. 342). All genetic screening is optional, and ideally, genetic carrier screening and counseling should be perormed beore pregnancy.

Neural-Tube Defects

raditionally, screening or neural-tube deects has been per- ormed as part o second-trimester aneuploidy screening. An elevation o maternal serum alpha-etoprotein (MSAFP) levels then prompted additional evaluation with ultrasound and/or amniocentesis. With the advent o other screening modalities or aneuploidy, second-trimester MSAFP testing is less requently obtained. For example, the expansion o second-trimester etal anatomical surveillance has been used to screen and identiy neural-tube deects (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017).

NUTRITIONAL COUNSELING

■ Weight Gain Recommendations

In 2009, the Institute o Medicine and National Research Council revised guidelines or weight gain in pregnancy and continued to stratiy suggested weight gain ranges based on prepregnancy body mass index (BMI) (Table 10-4). Te same recommendations apply to women in all age, race, and ethnic groups. Te American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2018n) endorses these measures. When the initial Institute o Medicine guidelines were ormulated, concern ocused on low-birthweight newborns. However, current emphasis is directed to the obesity epidemic. Te specic and relatively narrow range o recommended weight gains or obese women emphasizes the renewed interest in lower weight gains during pregnancy. Obesity is associated with signicantly greater risks or gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, macrosomia, cesarean delivery, and other complications (Chap. 51, p. 905). Te risk appears proportionate to prenatal weight gain. In a Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network cohort o more than 29,000 pregnant women, 51 percent had weight gain above and 21 percent below the guidelines

TABLE 10-4. Recommendations for Total and Rate of Weight Gain During Pregnancy

(Kominiarek, 2018). Tose with excessive weight gain had higher rates o hypertension and cesarean delivery. Tis risk is even greater in chronically hypertensive women (Ornaghi, 2018). Conversely, among 100,000 women with normal prepregnancy BMI, DeVader and colleagues (2007) ound that those who gained <25 lb during pregnancy had a lower risk or preeclampsia, ailed induction, cephalopelvic disproportion, cesarean delivery, and large-or-gestational age neonates. Tis cohort, however, had an increased risk or small-or-gestational age newborns.

■ Severe Undernutrition

Meaningul studies o nutrition in human pregnancy are exceedingly difcult to design because experimental dietary deciency is not ethical. In those instances in which severe nutritional deciencies have been induced as a consequence o social, economic, or political disaster, coincidental events have oten created many variables, the eects o which are not amenable to quantication. Some past experiences suggest, however, that in otherwise healthy women, a state o near starvation is required to establish clear dierences in pregnancy outcome. Tese are discussed in Chapter 47 (p. 827).

■ Weight Retention After Pregnancy

Not all the weight gained during pregnancy is lost during and immediately ater delivery. Schauberger and coworkers (1992) studied prenatal and postpartum weights in 795 women. Teir average weight gain was 28.6 lb or 12.9 kg. As shown in Figure 10-3, most maternal weight loss was at delivery— approximately 12 lb or 5.4 kg—and in the ensuing 2 weeks— approximately 9 lb or 4 kg. An additional 5.5 lb or 2.5 kg was lost between 2 weeks and 6 months postpartum. Tus, average retained pregnancy weight was 2.1 lb or 1 kg. Excessive weight gain is maniest by accrual o at and may be partially retained as long-term at (Berggren, 2016; Widen, 2015). Overall, the more weight that was gained during pregnancy, the more that was lost postpartum. And breasteeding duration is inversely related to weight retention (Jiang, 2018).

■ Dietary Reference Intakes—Recommended

Allowances

Periodically, the Institute o Medicine (2006, 2011) publishes recommended dietary allowances, including those or pregnant or lactating women. Some o its latest recommendations are summarized in Table 10-5. Certain prenatal vitamin–mineral supplements may lead to intakes well in excess o the recommended allowances. Moreover, the use o excessive supplements, which oten are sel-prescribed, has led to concern regarding nutrient toxicities during pregnancy. Tose with potentially toxic efects include iron, zinc, selenium, and vitamins A, B6, C, and D.

■ Calories

As shown in Figure 10-4, pregnancy requires an additional 80,000 kcal, mostly during the last 20 weeks. o meet this demand, a caloric increase o 100 to 300 kcal/d is recommended

FIGURE 10-3 Cumulative weight loss from last antepartum visit to 6 months postpartum. On average, 1 kg will be retained after pregnancy. *Significantly different from 2-week weight loss;

**Significantly different from 6-week weight loss. (Redrawn with permission from Schauberger CW, Rooney BL, Brimer LM: Factors that influence weight loss in the puerperium. Obstet Gynecol 79:424, 1992.)

TABLE 10-5. Recommended Daily Dietary Allowances for Pregnant and Lactating Women

during pregnancy (American Academy o Pediatrics and American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017). Tis greater intake, however, should not be divided equally during the course o pregnancy. Te Institute o Medicine (2006) recommends adding 0, 340, and 452 kcal/d to the estimated nonpregnant energy requirements in the rst, second, and third trimesters, respectively. Te addition o 1000 kcal/d or more results in at accrual (Jebeile, 2015).

Whenever caloric intake is inadequate, protein is metabolized rather than being spared or its vital role in etal growth and development. otal physiological requirements during pregnancy are not necessarily the sum o ordinary nonpregnant requirements plus those specic to pregnancy. For example, the additional energy required during pregnancy may be compensated in whole or in part by reduced physical activity (Hytten, 1991).

■ Protein

Protein requirements rise to meet the demands or growth and remodeling o the etus, placenta, uterus, and breasts, and or the expanded maternal blood volume (Chap. 4, p. 51). During the second hal o pregnancy, approximately 1000 g o protein are deposited, amounting to 5 to 6 g/d (Hytten, 1971). o accomplish this, protein intake that approximates 1 g/kg/d is recommended (see able 10-5). Data suggest this should be doubled in late gestation (Stephens, 2015). Most amino-acid levels in maternal plasma all markedly, including ornithine, glycine, taurine, and proline (Hytten, 1991). Exceptions during pregnancy are glutamic acid and alanine, the concentrations o which rise. Preerably, most protein is supplied rom animal sources, such as meat, milk, eggs, cheese, poultry, and sh. Tese urnish amino acids in optimal combinations. Milk and dairy products are considered nearly ideal sources o nutrients, especially protein and calcium, or pregnant or lactating women. Ingestion o specic sh and potential methylmercury toxicity are discussed later (p. 188).

■ Minerals

Te intakes recommended by the Institute o Medicine (2006) or various minerals are listed in able 10-5. With the exception o iron and iodine, practically all diets that supply sufcient calories or appropriate weight gain will contain enough minerals to prevent deciency. Iron requirements substantively rise during pregnancy, and reasons or this are discussed in Chapter 4 (p. 60). O the approximately 300 mg o iron transerred to the etus and placenta and the 500 mg incorporated into the expanding maternal hemoglobin mass, nearly all is used ater midpregnancy. During that time, iron requirements imposed by pregnancy and maternal excretion total approximately 7 mg/d (Pritchard, 1970). Few women have sufcient iron stores or dietary intake to supply this amount. Tus, the American Academy o Pediatrics and the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2017) endorse the recommendation by the National Academy o Sciences that at least 27 mg o elemental iron be supplemented daily to pregnant women. Tis amount is contained in most prenatal vitamins. As little as 30 mg o elemental iron, supplied as errous gluconate, sulate, or umarate, and taken daily throughout the latter hal o pregnancy, provides sufcient iron to meet pregnancy requirements and protect preexisting iron stores (Scott, 1970). Tis amount will also provide or iron requirements o lactation. Notably, in iron preparations, the number o milligrams o compound is ollowed by the milligrams o elemental iron, which is enclosed by parentheses. Te pregnant woman may benet rom 60 to 100 mg o elemental iron per day i she is obese, has a multietal gestation, begins supplementation late in pregnancy, takes iron irregularly, or has a depressed hemoglobin level. Te woman who is overtly anemic rom iron de- ciency responds well to oral supplementation with iron salts. In response, serum erritin levels rise more than the hemoglobin concentration (Daru, 2016).

Iodine also is needed, and the recommended iodine allowance is 220 µg/d (see able 10-5). Te use o iodized salt and bread products is recommended during pregnancy to oset the increased etal requirements and maternal renal losses o iodine. Despite this, iodine intake has declined substantially in the past 15 years, and in some areas it is probably inadequate (Caldwell, 2013; Chittimoju, 2019). Severe maternal iodine deciency predisposes ospring to endemic cretinism, which is characterized by multiple severe neurological deects. In parts o China and Arica, where this condition is common, iodide supplementation very early in pregnancy prevents some cretinism cases (Cao, 1994). o obviate this, most prenatal supplements now contain various quantities o iodine (Patel, 2019).

Calcium is retained by the pregnant woman during gestation and approximates 30 g. Most o this is deposited in the etus late in pregnancy (Pitkin, 1985). Tis amount o calcium represents only approximately 2.5 percent o total maternal calcium, most o which is in bone and can readily be mobilized or etal growth. As another potential use, routine calcium supplementation to prevent preeclampsia is ineective (Chap. 40, p. 704).

Zinc deciency i severe may lead to poor appetite, suboptimal growth, and impaired wound healing. During pregnancy, the recommended daily intake approximates 12 mg. But, the sae level o zinc supplementation or pregnant women is not clearly established. Vegetarians have lower zinc intakes (Foster, 2015). Te bulk o studies support zinc supplementation only

FIGURE 10-4 Cumulative kilocalories required for pregnancy. (Redrawn with permission from Chamberlain G, Broughton-Pipkin F [eds]: Clinical Physiology in Obstetrics, 3rd ed. Oxford, Blackwell Science, 1998.)

in zinc-decient women in poor-resource countries (Nossier, 2015; Ota, 2015).

Magnesium deciency as a consequence o pregnancy has not been recognized. Undoubtedly, during prolonged illness with no magnesium intake, the plasma level might become critically low, as it would in the absence o pregnancy. We have observed this deciency during pregnancies in some with previous intestinal bypass surgery. Instead, as a preventive agent, Sibai and colleagues (1989) randomly assigned 400 normotensive primigravidas to receive 365-mg elemental magnesium supplementation or placebo tablets rom 13 to 24 weeks’ gestation. Supplementation did not improve any measures o pregnancy outcome. race metals include copper, selenium, chromium, and manganese, which all have important roles in certain enzyme unctions. In general, most are provided by an average diet.

Selenium deciency is maniested by a requently atal cardiomyopathy in young children and reproductive-aged women. Conversely, selenium toxicity resulting rom oversupplementation also has been observed. Selenium supplementation is not needed in American women.

Potassium concentrations in maternal plasma decline by approximately 0.5 mEq/L by midpregnancy (Brown, 1986). Potassium deciency develops in the same circumstances as in nonpregnant individuals. One common example in pregnant women is hyperemesis gravidarum.

Fluoride metabolism is not altered appreciably during pregnancy (Maheshwari, 1983). Horowitz and Heietz (1967) concluded that no additional ospring benets accrued rom maternal ingestion o uoridated water i the newborn ingested such water rom birth. Sa Roriz Fonteles and associates (2005) studied microdrill biopsies o deciduous teeth and concluded that antenatal uoride provided no additional uoride uptake compared with postnatal uoride alone. Finally, supplemental uoride ingested by lactating women does not raise the uoride concentration in breast milk (Ekstrand, 1981).

■ Vitamins

Te increased requirements or most vitamins during pregnancy shown in able 10-5 usually are supplied by any general diet that provides adequate calories and protein. Te exception is olic acid during times o unusual requirements, such as pregnancy complicated by protracted vomiting, hemolytic anemia, or multiple etuses. Tat said, in impoverished countries, routine multivitamin supplementation reduced the incidence o low-birthweight and growth-restricted etuses but did not alter preterm delivery or perinatal mortality rates (Fawzi, 2007).

Folic acid supplementation in early pregnancy can lower neural-tube deect risks (Chap. 15, p. 276). For example, the CDC (2004) estimated that the number o aected pregnancies had decreased rom 4000 per year to approximately 3000 per year ater mandatory ortication o cereal products with olic acid in 1998. Perhaps more than hal o all neural-tube deects can be prevented with daily intake o 400 µg o olic acid throughout the periconceptional period (Centers or Disease Control and Prevention, 2019a). Evidence also suggests that olate insu- ciency has a global eect on brain development (Ars, 2016). Putting 140 µg o olic acid into each 100 g o grain products may increase the olic acid intake o the average American woman o childbearing age by 100 µg/d. Because nutritional sources alone are insufcient, however, olic acid supplementation is still recommended.

A woman with a prior child with a neural-tube deect can reduce the 2- to 5-percent recurrence risk by more than 70 percent with a daily 4-mg olic acid supplement taken during the month beore conception and during the rst trimester. As emphasized by the American Academy o Pediatrics and the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2017), this dose should be consumed as a separate supplement and not as multivitamin tablets. Tis practice avoids excessive intake o at-soluble vitamins.

Vitamin A, although essential, has been associated with congenital malormations when taken during pregnancy in high doses (>10,000 IU/d). Tese malormations are similar to those produced by the vitamin A derivative isotretinoin (Accutane), which is a potent teratogen (Chap. 8, p. 155). Beta- carotene, the precursor o vitamin A ound in ruits and vegetables, does not produce vitamin A toxicity. Most prenatal vitamins contain vitamin A in doses considerably below the teratogenic threshold. Dietary intake o vitamin A in the United States appears to be adequate, and additional supplementation is not routinely recommended. In contrast, vitamin A deciency is an endemic nutritional problem in the developing world (McCauley, 2015). Vitamin A deciency, whether overt or subclinical, is associated with night blindness and with an increased risk o maternal anemia and spontaneous preterm birth (West, 2003).

Vitamin B12 plasma levels drop in normal pregnancy, mostly as a result o reduced plasma levels o their carrier proteins— transcobalamins. Vitamin B12 occurs naturally only in oods o animal origin, and strict vegetarians may give birth to neonates whose B12 stores are low. Likewise, because breast milk o a vegetarian mother contains little vitamin B12, the deciency may become proound in the breasted inant (Higginbottom, 1978). Excessive ingestion o vitamin C also can lead to a unctional deciency o vitamin B12. Although its role is still controversial, vitamin B12 deciency may be an independent actor associated with neural-tube deects (Molloy, 2018).

Vitamin B6, which is pyridoxine, does not require supplementation in most gravidas (Salam, 2015). For women at high risk or inadequate nutrition, a daily 2-mg supplement is recommended. As discussed on page 191, vitamin B6, when combined with the antihistamine doxylamine, is helpul in many cases o nausea and vomiting o pregnancy.

Vitamin C allowances during pregnancy are 80 to 85 mg/d— approximately 20 percent more than when nonpregnant (see able 10-5). A reasonable diet should readily provide this amount, and supplementation is unnecessary (Rumbold, 2015). Maternal plasma levels decline during pregnancy, whereas cord blood levels are higher. Tis is a phenomenon observed with most water-soluble vitamins.

Vitamin D is a at-soluble vitamin. Ater being metabolized to its active orm, it boosts the efciency o intestinal calcium absorption and promotes bone mineralization and growth. Unlike most vitamins that are obtained exclusively rom dietary intake, vitamin D is also synthesized endogenously with exposure to sunlight. Vitamin D deciency is common during pregnancy. Tis is especially true in high-risk groups such as women with limited sun exposure, vegetarians, and ethnic minorities—particularly those with darker skin (Bodnar, 2007). Maternal deciency can cause disordered skeletal homeostasis, congenital rickets, and ractures in the newborn (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017j). However, vitamin D supplementation in women with asthma may decrease the likelihood o childhood asthma in their ospring (Litonjua, 2016). Te Food and Nutrition Board o the Institute o Medicine (2011) established that an adequate intake o vitamin D during pregnancy and lactation was 15 µg/d (600 IU/d). In women suspected o having vitamin D deciency, serum levels o 25-hydroxyvitamin D can be obtained. Even then, the optimal levels in pregnancy have not been established (De-Regil, 2016).

■ Pragmatic Nutritional Surveillance

Although researchers continue to study the ideal nutritional regimen or the pregnant woman and her etus, basic tenets or the clinician include:

1. Advise the pregnant woman to eat ood types she wants in reasonable amounts and salted to taste.

2. Ensure that ood is amply available or socioeconomically deprived women.

3. Monitor weight gain and align goals with the Institute o Medicine recommendations.

4. Explore ood intake by dietary recall periodically to discover the occasional nutritionally errant diet.

5. Give tablets o simple iron salts that provide at least 30 mg o elemental iron daily. Give olate supplementation beore and in the early weeks o pregnancy. Provide iodine supplementation in areas o known dietary insufciency.

6. Recheck the hematocrit or hemoglobin concentration at 28 to 32 weeks’ gestation to detect signicant anemia.

COMMON CONCERNS

■ Employment

More than hal o the children in the United States are born to working mothers. Several ederal laws have been passed to protect pregnant workers. Tese prohibit employers rom excluding women rom job categories on the basis that they are or might become pregnant. Te Family and Medical Leave Act o 1993 requires that covered employers must grant up to 12 work weeks o unpaid leave to an employee or the birth and care o a newborn child.

In the absence o complications, most women can continue to work until labor onset (American Academy o Pediatrics and American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017). Some types o work, however, may increase pregnancy complication risks. According to the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2018b), risks o preterm birth are slightly to modestly increased with standing or walking at work >3 hours daily, liting and carrying >5 kg, or physically exerting onesel at work. In a prospective study o more than 900 healthy nulliparas, women who worked had a veold higher risk o preeclampsia (Higgins, 2002). Tus, any occupation that subjects the gravida to severe physical strain should be avoided. Ideally, no work or play is continued to the extent that undue atigue develops. Adequate periods o rest should be provided.

■ Exercise

In general, pregnant women do not need to limit exercise, provided they do not become excessively atigued or risk injury (Davenport, 2016). Clapp and associates (2000) reported that both placental size and birthweight were signicantly greater in women who exercised. Duncombe and coworkers (2006) reported similar ndings in 148 women. In contrast, Magann and colleagues (2002) prospectively analyzed exercise behavior in 750 healthy women and ound that working women who exercised had smaller neonates and more dysunctional labors. Te American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2020a) advises a thorough clinical evaluation beore recommending an exercise program. In the absence o contraindications listed in Table 10-6, pregnant women are encouraged to engage in regular, moderate-intensity physical activity or at least 150 minutes each week. Such activity has been shown to not adversely alter uterine artery Doppler studies (Szymanski, 2018). Each activity should be reviewed individually or its potential risk. Examples o sae activities are walking, running, swimming, stationary cycling, and low-impact aerobics. However, they should rerain rom activities with a high risk o alling or abdominal trauma. Similarly, scuba diving is avoided because the etus is at increased risk or decompression sickness (Reid, 2018).

In the setting o certain pregnancy complications, it is wise to abstain rom exercise and even limit physical activity. Some women with pregnancy-associated hypertensive disorders, preterm labor, placenta previa, or severe cardiac or pulmonary disease may accrue advantages rom being sedentary. Also, those with multiple or suspected growth-restricted etuses may be served by greater rest.

TABLE 10-6. Some Contraindications to Exercise During Pregnancy

Significant cardiovascular or pulmonary disease: chest pain, calf pain or swelling

Significant risk for preterm labor: cerclage, multifetal gestation, significant bleeding, threatened preterm labor, ruptured membranes

Obstetrical complications: preeclampsia, placenta previa, anemia, poorly controlled diabetes or epilepsy, morbid obesity, fetal-growth restriction

Summarized from American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017g; The American Academy of Pediatrics, 2017.

■ Seafood Consumption

Fish are an excellent source o protein, are low in saturated ats, and contain omega-3 atty acids. It is recommended that pregnant women ingest 8 to 12 ounces o sh weekly, but no more than 6 ounces o albacore or “white” tuna (U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2019). Because nearly all sh and shell- sh contain trace amounts o mercury, pregnant and lactating women are advised to avoid specic types o sh with potentially high methylmercury levels. Tese include shark, swordsh, king mackerel, and tile sh. I the mercury content o locally caught sh is unknown, overall sh consumption should be limited to 6 ounces per week. Finally, to help avert listeriosis, eating raw or undercooked sh is avoided (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017j).

■ Lead Screening

Maternal lead exposure is associated with several adverse maternal and etal outcomes across a range o maternal blood lead levels (aylor, 2015). Tese include gestational hypertension, miscarriage, low birthweight, and neurodevelopmental impairments in exposed pregnancies. Te levels at which these risks rise remains unclear. However, recognizing that such exposure remains a signicant health issue or reproductive-aged women, the CDC (2010a) provides guidance or screening and managing exposed pregnant and lactating women. Tese guidelines, which have been endorsed by the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2018), recommend blood lead testing only i a risk actor is identied. I the levels are >5 µg/dL, the lead source is sought and removed. Subsequent blood levels are obtained. Blood lead levels >45 µg/dL are consistent with lead poisoning, and women in this group may be candidates or chelation therapy. Aected pregnancies are best managed in consultation with lead poisoning treatment experts. National and state resources are available at the CDC website: www.cdc.gov/nceh/lead/.

■ Automobile and Air Travel

Pregnant women are encouraged to wear properly positioned three-point restraints as protection against automobile accident injury (Chap. 50, p. 892). Te lap portion o the restraining belt is placed under the abdomen and across her upper thighs. Te belt should be comortably snug. Te shoulder belt also is rmly positioned between the breasts. Airbags should not be disabled or the pregnant woman.

In general, air travel in a properly pressurized aircrat has no harmul eect on pregnancy. Tus, in the absence o obstetrical or medical complications, the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2018a) has concluded that pregnant women can saely y up to 36 weeks’ gestation. It is recommended that they observe the same precautions or air travel as the general population. Seatbelts are used while seated. Support stockings, periodic lower extremity movement, and at least hourly ambulation help lower the venous thromboembolism threat. Signicant risks with travel, especially international travel, are inectious disease acquisition and development o complications remote rom adequate health-care resources.

■ Coitus

In healthy pregnant women, sexual intercourse usually is not harmul. Whenever miscarriage, placenta previa, or preterm labor threatens, however, coitus is avoided. Nearly 10,000 women enrolled in a prospective investigation by the Vaginal Inection and Prematurity Study Group were interviewed regarding sexual activity (Read, 1993). Tey reported a decreased requency o coitus with advancing gestation. By 36 weeks, 72 percent had intercourse less than once weekly. Te decline is attributed to lower desire and ear o harming the pregnancy (Staruch, 2016).

Intercourse specically late in pregnancy is not harmul. Sayle and colleagues (2001) reported no increased—and actually a decreased—risk o delivery within 2 weeks o intercourse. an and associates (2007) studied women scheduled or nonurgent labor induction and ound that spontaneous labor ensued at equal rates in groups either participating in or abstaining rom intercourse.

Oral-vaginal intercourse is occasionally hazardous. Aronson and Nelson (1967) described a atal air embolism late in pregnancy as a result o air blown into the vagina during cunnilingus. Other near-atal cases have been described (Bernhardt, 1988).

■ Dental Care

Examination o the teeth is included in the prenatal examination, and good dental hygiene is encouraged. Indeed, periodontal disease is linked to preterm labor. Unortunately, although its treatment improves dental health, it does not prevent preterm birth (Daalderop, 2018). Dental caries are not aggravated by pregnancy. Importantly, pregnancy is not a contraindication to dental treatment including dental radiographs (American Academy o Pediatrics and American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017).

■ Immunization

Current recommendations or immunization during pregnancy are summarized in Table 10-7. Well-publicized concerns regarding a causal link between childhood exposure to the thimerosal preservative in some vaccines and neuropsychological disorders have led some parents to vaccine prohibition. Although controversy continues, these associations have been proven groundless. Tus, many vaccines may be used in pregnancy (Munoz, 2019). Te American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2020c) stresses the importance o integrating an eective vaccine strategy into the care o both obstetrical and gynecological patients. Te College urther emphasizes that inormation on the saety o vaccines given during pregnancy is subject to change, and recommendations can be ound on the CDC website at www.cdc.gov/vaccines.

Inuenza and tetanus–diphtheria–acellular pertussis (dap) vaccinations are recommended routinely or all pregnant women (Munoz, 2019; Sperling, 2018b). Others are recommended or specic indications (see able 10-7). Women who are susceptible to rubella should receive measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccination postpartum. Tis vaccine is contraindicated during pregnancy.

TABLE 10-7. Recommendations for Immunization During Pregnancy and Postpartum

■ Caffeine

Whether adverse pregnancy outcomes are related to caeine consumption is somewhat controversial. As summarized rom Chapter 11 (p. 200), heavy intake o coee each day—approximately ve cups or 500 mg o caeine—slightly raises the miscarriage risk. Studies o “moderate” intake—less than 200 mg daily—did not nd a higher risk. It is unclear i caeine consumption is associated with preterm birth or impaired etal growth. Clausson and coworkers (2002) ound no association between caeine consumption <500 mg/d and low birthweight, etal-growth restriction, or preterm delivery. Bech and associates (2007) randomly assigned more than 1200 pregnant women who drank at least three cups o coee per day to caeinated versus decaeinated coee. Tey ound no dierence in birthweight or gestational age at delivery between groups. Te CARE Study Group (2008), however, evaluated 2635 low-risk pregnancies and reported a 1.4-old risk or etal-growth restriction among those whose daily ca- eine consumption was >200 mg/d compared with those who consumed <100 mg/d. Te American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2018g) concludes that moderate consumption o caeine—less than 200 mg/d—does not appear to be associated with miscarriage or preterm birth, but that the relationship between caeine consumption and etal-growth restriction remains unsettled.

■ Nausea and Heartburn

Nausea and vomiting are common complaints during the rst hal o pregnancy. Tese vary in severity and usually commence between the rst and second missed menstrual period and continue until 14 to 16 weeks’ gestation. Although nausea and vomiting tend to be worse in the morning—thus termed morning sickness—both symptoms requently continue throughout the day. Lacroix and associates (2000) ound that nausea and vomiting were reported by three ourths o pregnant women and lasted an average o 35 days. Hal had relie by 14 weeks’ gestation, and 90 percent by 22 weeks’ gestation. In 80 percent o these women, nausea lasted all day. reatment o pregnancy-associated nausea and vomiting seldom provides complete relie, but symptoms can be minimized. Eating small meals at requent intervals is valuable. One systematic literature search reported that the herbal remedy ginger was likely eective (Borrelli, 2005). Mild symptoms usually respondto vitamin B6 given with doxylamine, but some women require phenothiazine or H1-receptor blocking antiemetics (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2018h). In some with hyperemesis gravidarum, vomiting is so severe that dehydration, electrolyte and acid-base disturbances, and starvation ketosis become serious problems (Chap. 57, p. 1014).

Heartburn is another common complaint o gravidas and is caused by gastric content reux into the lower esophagus. Te greater requency o regurgitation during pregnancy most likely results rom upward displacement and compression o the stomach by the uterus, combined with relaxation o the lower esophageal sphincter. Avoiding bending over or lying at can be preventive. In most pregnant women, symptoms are mild and relieved by a regimen o more requent but smaller meals. Antacids may provide considerable relie (Phupong, 2015).

Specically, aluminum hydroxide, magnesium trisilicate, or magnesium hydroxide are given alone or in combination. Management o heartburn or nausea that does not respond to simple measures is discussed in Chapter 57 (p. 1017).

■ Pica and Ptyalism

Te craving or strange oods is termed pica. Worldwide, its prevalence among pregnant women is estimated to be 30 percent (Fawcett, 2016). At times, nonoods such as ice (pagophagia), starch (amylophagia), or clay (geophagia) may predominate.

Tis desire is considered by some to be triggered by severe iron deciency (Epler, 2017). Although such cravings usually abate ater deciency correction, not all pregnant women with pica are iron decient. Indeed, i strange “oods” dominate the diet, iron deciency will be aggravated or will develop eventually. Patel and colleagues (2004) prospectively completed a dietary inventory on more than 3000 women during the second trimester. Te prevalence o pica was 4 percent. Te most common nonood items ingested were starch in 64 percent, dirt in 14 percent, sourdough in 9 percent, and ice in 5 percent.

Women during pregnancy are occasionally distressed by prouse salivation—ptyalism. Although usually unexplained, ptyalism sometimes appears to ollow salivary gland stimulation by the ingestion o starch. It commonly occurs with hyperemesis gravidarum (Bronshtein, 2018).

■ Headache or Backache

Headaches are common in pregnancy. At least 5 percent o pregnancies are estimated to be complicated by new-onset or new-type headache (Spierings, 2016). Acetaminophen is suitable or treatment o most, and an in-depth discussion is ound in Chapter 63 (p. 1127).

Low back pain to some extent is reported by nearly 70 percent o gravidas (Liddle, 2015). Minor degrees ollow excessive strain or signicant bending, liting, or walking. It can be reduced by squatting rather than bending when reaching down, by using a back-support pillow when sitting, and by avoiding high-heeled shoes. Back pain complaints increase with progressing gestation and are more prevalent in obese women and those with a history o low back pain. In some cases, troublesome pain may persist or years ater the pregnancy (Norén, 2002). Severe back pain should not be attributed simply to pregnancy until a thorough orthopedic examination has been conducted. Severe pain has other uncommon causes that include pregnancyassociated osteoporosis, disc disease, vertebral osteoarthritis, or septic arthritis (Smith, 2008). More commonly, muscular spasm and tenderness are classied clinically as acute strain or brositis.

Although evidence-based clinical research directing care in pregnancy is limited, low back pain usually responds well to analgesics, heat, and rest. Acetaminophen may be used as needed. Nonsteroidal antiinammatory drugs also may be benecial but are used only in short courses to avoid etal eects (Chap. 8, p. 151). Muscle relaxants that include cyclobenzaprine or bacloen may be added when needed. Once acute pain is improved, stabilizing and strengthening exercises provided by physical therapy help improve spine and hip stability, which is essential or the increased load o pregnancy. For some, a support belt that stabilizes the sacroiliac joint may be helpul (Gutke, 2015).

■ Varicosities and Hemorrhoids

Venous leg varicosities have a congenital predisposition and accrue with advancing age. Tey can be aggravated by actors that raise lower-extremity venous pressures, such as an enlarging uterus. Femoral venous pressures in the supine gravida rise rom 8 mm Hg in early pregnancy to 24 mm Hg at term. Tus, leg varicosities typically worsen as pregnancy advances, especially with prolonged standing. Symptoms vary rom cosmetic blemishes and mild discomort at the end o the day to severe discom- ort that requires prolonged rest with eet elevation. reatment is generally limited to periodic rest with leg elevation, elastic stockings, or both. Surgical correction during pregnancy generally is not advised, although rarely the symptoms may be so severe that injection, ligation, or even stripping o the veins is necessary.

Supercial varicosities are a risk actor or deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism (Chap. 55, p. 980). Vulvar varicosities requently coexist with leg varicosities, but they may appear without other venous pathology. Uncommonly, they become massive and almost incapacitating (Pratilas, 2018). I these large varicosities rupture, either spontaneously or at the time o delivery, blood loss can be severe. reatment is with specially tted pantyhose that will also minimize lower extremity varicosities. With particularly bothersome vulvar varicosities, a oam rubber pad suspended across the vulva by a belt can be used to exert pressure on the dilated veins.

Hemorrhoids are rectal vein varicosities and may rst appear during pregnancy as pelvic venous pressures rise. Commonly, they are recurrences o previously encountered hemorrhoids. Up to 40 percent o pregnant women develop these (Poskus, 2014). Pain and swelling usually are relieved by topically applied anesthetics, warm soaks, and stool-sotening agents. With thrombosis o an external hemorrhoid, pain can be considerable. Tis may be relieved by incision and removal o the clot ollowing injection o a local anesthetic.

■ Sleeping and Fatigue

Beginning early in pregnancy, many women experience atigue and need greater amounts o sleep. Te soporic eect o progesterone contributes but may be compounded in the rst trimester by nausea and vomiting. In the latter stages, general discomorts, urinary requency, and dyspnea can be additive.

Sleep-disordered breathing may be associated with signicant morbidities such as hypertensive disorders o pregnancy, stillbirth, and preterm delivery (Brown, 2018; Dominguez, 2018). Moreover, sleep efciency appears to progressively diminish as pregnancy advances. Wilson and associates (2011) perormed overnight polysomnography and observed that women in the third trimester had poorer sleep efciency, more awakenings, and less o both stage 4 (deep) and rapid-eye-movement sleep. Women in the rst trimester also were aected, but to a lesser extent. Daytime naps and mild sedatives at bedtime such as diphenhydramine (Benadryl) can be helpul.

■ Cord Blood Banking

Cord blood contains hemopoietic stem cells that can be used to treat more than 70 types o diseases. Tese include immunological and genetic diseases and some orms o cancer. O the two cord blood bank types, public banks promote allogeneic donation, or use by a related or unrelated recipient, similar to blood product donation. Private banks store stem cells or uture autologous use and charge ees or initial processing and annual storage. Te American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2020e) has concluded that i a woman requests data on umbilical cord banking, inormation regarding advantages and disadvantages o public versus private banking should be explained. Some states have passed laws that require physicians to inorm patients about cord blood banking options. Importantly, ew transplants have been perormed by using cord blood stored in the absence o a known indication in the recipient (Screnci, 2016). Te likelihood that cord blood would be used or the child or amily member o the donor couple is considered remote. Instead, it is recommended that directed donation be considered when an immediate amily member carries the diagnosis o a specic condition known to be treatable by hemopoietic transplantation

Nhận xét

Đăng nhận xét