Chapter 12. Ectopic Pregnancy

BS. Nguyễn Hồng Anh

Following ertilization and allopian tube transit, the blastocyst normally implants in the endometrial lining o the uterine cavity. Implantation elsewhere is considered ectopic. In

the United States, numbers rom an insurance database and

rom Medicaid claims showed ectopic pregnancy rates o 1.54

percent and 1.38 percent, respectively, in 2013 (ao, 2017).

Ectopic implantation accounts or 3 percent o all pregnancyrelated deaths (Creanga, 2017). Fortunately, beta-human

chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) assays and transvaginal

sonography (VS) aid earlier diagnosis, maternal survival, and

ertility conservation.

TUBAL PREGNANCY

■ Classfcaton

O ectopic pregnancies, nearly 95 percent implant in the allopian tube’s various segments (Fig. 2-13, p. 26). Te ampulla

(70 percent) is the most requent site (Fig. 12-1). Te rate or

isthmic implantation is 12 percent; mbrial, 11 percent; and

interstitial, 2 percent (Bouyer, 2002). Nontubal ectopic pregnancies compose the remaining 5 percent and implant in the

ovary, peritoneal cavity, cervix, or prior cesarean scar. Occasionally, a multietal pregnancy contains one conceptus with

normal uterine implantation and the other implanted ectopically. Tis is termed a heterotopic pregnancy (p. 231).

For all ectopic pregnancy sites, management is inuenced by

pregnancy viability, gestational age, maternal health, desires or

the index pregnancy and or uture ertility, physician skill, and

available resources. Regardless o location, D-negative women

with an ectopic pregnancy are given anti-D immunoglobulin.

In rst-trimester pregnancies, a single intramuscular 50- or

120-μg dose is appropriate. Later gestations are given 300 μg

(American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2019b).

■ Rsks

Abnormal allopian tube anatomy underlies most cases o tubal

ectopic pregnancy. Surgeries or a prior tubal pregnancy, or

ertility restoration, or or sterilization coner the highest risk.

Ater one prior ectopic pregnancy, the chance o another nears

10 percent (de Bennetot, 2012). Previous tubal inection, which

can distort normal tubal anatomy, is another risk. Specically,

one episode o salpingitis can be ollowed by a subsequent ectopic pregnancy in up to 9 percent o women (Westrom, 1992).

Peritubal adhesions that orm rom salpingitis, appendicitis, or

endometriosis also raise chances.

Inertility and the use o assisted reproductive technologies

(AR) to overcome it are linked to increased ectopic pregnancy

rates (Li, 2015; Perkins, 2015). Newer techniques aim to lower

this rate with AR (Londra, 2015; Zhang, 2017). Smoking

is another known association, although the underlying mechanism is unclear (Hyland, 2015). Last, with any orm o contraception, the absolute number o ectopic pregnancies declines

because pregnancy is eectively prevented. However, some

methods more efciently prevent intracavity implantation and

with their ailure, ectopic implantation is avored. Tese methods are tubal sterilization, intrauterine devices (IUDs), and

progestin-only contraceptives.

■ Pathogeness and Potental Outcomes

With tubal pregnancy, because the allopian tube lacks a submucosal layer, the ertilized ovum promptly burrows through

the epithelium. Te zygote comes to lie near or within the muscularis, which is invaded by rapidly prolierating trophoblast.

Potential outcomes rom this include tubal rupture, tubal abortion, or pregnancy ailure with resolution.

With rupture, the invading and expanding conceptus can

tear the allopian tube. ubal ectopic pregnancies usually rupture spontaneously but may occasionally burst ollowing coitus

or bimanual examination. Hemorrhage usually persists and can

become lie threatening.

Tubal abortion describes the pregnancy’s passage out the allopian tube’s distal end. Subsequently, hemorrhage may cease,

and symptoms eventually disappear. However, bleeding instead

can progress to induce symptoms as long as products remain

in the tube. Blood slowly issues rom the tubal mbria into

the peritoneal cavity and pools in the rectouterine cul-de-sac.

I the mbriated extremity is occluded, the allopian tube may

gradually distend with blood to orm a hematosalpinx. Rarely,

an aborted etus will secondarily implant on a peritoneal surace

and become an abdominal pregnancy (p. 231).

Last, spontaneous ailure reects ectopic pregnancy death and

subsequent reabsorption. Tese are now more regularly identi-

ed by current sensitive β-hCG assays and surveillance.

Distinctions between acute ectopic pregnancy, just described,

and chronic ectopic pregnancy also can be drawn. Acute ectopic

pregnancies are more common, produce a high serum β-hCG

level, and grow rapidly, leading to a timely diagnosis. Tese

carry a greater risk o rupture (Barnhart, 2003c). With chronic

ectopic pregnancy, abnormal trophoblasts die early, and thus

serum β-hCG levels are negative or are low and static. Chronic

ectopic pregnancies typically rupture late, i at all, but commonly orm a persistent complex pelvic mass. Tis sonographic

nding, rather than patient symptoms, oten is the reason that

prompts diagnostic surgery (emper, 2019).

■ Clncal Manfestatons

Sources o abdominal pain during pregnancy are extensive.

Uterine conditions include miscarriage, inection, degenerating

or enlarging leiomyomas, or round-ligament pain. Adnexal pain

may reect ectopic pregnancy or ovarian masses that are hemorrhagic, ruptured, or torsed. Appendicitis, renal stone, cystitis, and gastroenteritis are some nongynecological reasons or

lower abdominal pain in early pregnancy. Tus, an initial urine

β-hCG assay, urinalysis, and measure o hemoglobin or hematocrit are routine. A complete blood count (CBC) to assess the

white blood cell count may be preerred i serious inection is a

possible diagnosis. A positive urine pregnancy test result should

prompt a serum β-hCG assay or those with pain or bleeding.

Beore rupture, symptoms and signs o ectopic pregnancy

are oten subtle or absent. Te classic triad is amenorrhea that

is ollowed by pain and vaginal bleeding. With tubal rupture,

lower abdominal and pelvic pain is usually severe and requently described as sharp, stabbing, or tearing. Some degree

o vaginal spotting or bleeding is reported by most women with

tubal pregnancy. Although prouse vaginal bleeding suggests an

incomplete abortion, such bleeding occasionally is seen with

tubal gestations. Moreover, tubal pregnancy can lead to signi-

cant intraabdominal hemorrhage. Neck or shoulder pain, especially on inspiration, develops in women with diaphragmatic

irritation rom a sizable hemoperitoneum. Vertigo and syncope

may reect hemorrhage-related hypovolemia.

O physical ndings, abdominal palpation elicits tenderness.

Bimanual pelvic examination may reveal a mass and tenderness,

but this examination should be limited and gentle to avoid iatrogenic rupture. Te uterus itsel can be slightly enlarged due to

hormonal stimulation. Responses to moderate bleeding include

no change in vital signs, a slight rise in blood pressure, or a

vasovagal response with bradycardia and hypotension. Blood

pressure will all and pulse will rise only i bleeding continues

and hypovolemia becomes signicant.

O laboratory ndings, hemoglobin or hematocrit readings

may at rst show only a slight reduction, even ater substantive

hemorrhage. Tus, ater acute hemorrhage, a trending decline

in hemoglobin or hematocrit levels over several hours is a more

valuable index o blood loss than is the initial level. In approximately hal o women with a ruptured ectopic pregnancy, varying degrees o leukocytosis may reach 30,000/μL.

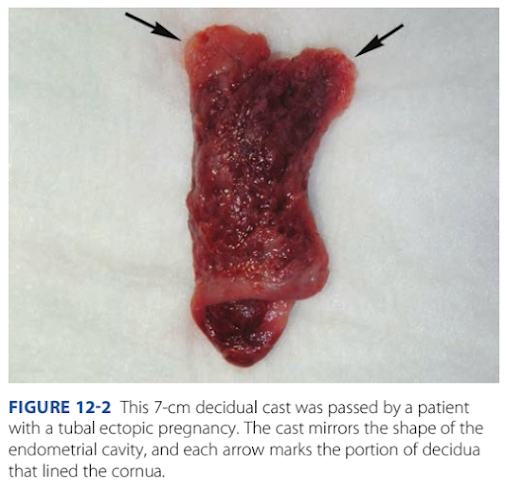

Decidua is endometrium that is hormonally prepared or

pregnancy. Te degree to which the endometrium is converted

with ectopic pregnancy varies. Tus, in addition to bleeding,222 First- and Second-Trimester Pregnancy Loss

Section 5

women with ectopic tubal pregnancy may pass a decidual cast.

Tis is the entire sloughed endometrium that takes the orm

o the endometrial cavity (Fig. 12-2). Importantly, decidual

sloughing may also occur with miscarriage. Tus, tissue is care-

ully examined by the provider and then submitted to evaluate

or histological evidence o a conceptus. I no clear gestational

sac is seen by inspection or i no villi are identied histologically,

the possibility o ectopic pregnancy must still be considered.

TUBAL PREGNANCY DiAGNOSiS

For ectopic pregnancy, physical ndings, serum β-hCG level

measurement, VS, and at times diagnostic surgery are tools

or diagnosis. Women with evidence o tubal rupture undergo

prompt surgery. For all other hemodynamically stable women

without a clearly identied pregnancy, diagnostic strategies use

these tools to identiy ectopic pregnancy.

Strategies involve trade-os. Tose that maximize ectopic

pregnancy detection may terminate a normal intrauterine pregnancy (IUP). Conversely, those that reduce the potential interruption o a normal IUP can delay ectopic pregnancy diagnosis.

Patient desires or the index pregnancy are sought and inuence

these trade-os.

■ BetaHuman Choronc Gonadotropn

Rapid and accurate determination o pregnancy is a undamental

step. hCG is a glycoprotein produced by placental trophoblast

and can be detected in serum in early pregnancy. Current pregnancy tests are immunoassays that seek the beta subunit o hCG.

Lower limits o detection are 20 to 25 mIU/mL or urine and

≤5 mIU/mL or serum (Greene, 2015). Dierent assays can have

results that vary by 5 to 10 percent. Tus, serial values are more

reliable when perormed by the same laboratory (Desai, 2014).

For women with a positive pregnancy test result plus bleeding

or pain, an initial VS is typically perormed to locate the gestation. Te initial β-hCG level sets expectations or anticipated

VS nding. With values above a discriminatory threshold,

a normal IUP is expected to be seen within the uterus. Some

institutions set their discriminatory threshold at ≥1500 mIU/

mL, whereas others use ≥2000 mIU/mL. Connolly and associates (2013) suggested an even higher threshold. Tey noted that

with live IUPs, a gestational sac was seen 99 percent o the time

in those with a discriminatory level >3510 mIU/mL.

■ Transvagnal Sonography

Pregnancy of Unknown Location

I a yolk sac, embryo, or etus is ound within the uterus or within

the adnexa, a diagnosis is made. However, i no evidence o an

IUP is seen with VS, the diagnosis is a pregnancy o unknown

location (PUL). Most PULs reect: (1) a ailing IUP, (2) recent

completed abortion, (3) early IUP, or (4) ectopic pregnancy.

Without clear evidence or ectopic pregnancy, serial β-hCG

level assessment is reasonable, and a second level is obtained 48

hours ater the rst. Tis practice averts unnecessary methotrexate therapy and avoids harming an early, normal IUP.

With early, normal IUPs, Barnhart and coworkers (2004b)

reported a 53-percent minimum rise over 48 hours. Seeber and

colleagues (2006) ound an even more conservative minimal

35-percent rise in normal IUPs. With multietal gestation, this

same anticipated rate o rise is expected (Chung, 2006).

With a PUL ultimately diagnosed as a ailed IUP, a pattern

o β-hCG level decline also can be anticipated, and levels drop

rapidly (able 11-1, p. 202) (Barnhart, 2004a). Sometimes,

PULs ail beore their location is identied. With ailing PULs,

Butts and coworkers (2013) ound rates o decline that ranged

rom 35 to 50 percent at 48 hours and 66 to 87 percent at 7

days or starting hCG values between 250 and 5000 mIU/mL.

Despite these benchmarks, a third o women with an ectopic pregnancy can also have a 53-percent rise at 48 hours (Silva,

2006). Overall, approximately hal o ectopic pregnancies show

declining β-hCG levels, whereas the other hal have rising levels. Importantly, despite a declining β-hCG level, a resolving

ectopic pregnancy may rupture. Rupture at low values likely

reects partial disruption o the vascular connection between

trophoblast and maternal vessels. Here, although β-hCG is

produced, it is unable to enter circulation and be detected.

Ater the initial two β-hCG tests during PUL assessment,

additional levels are drawn every 2 to 7 days. In general, testing

is typically more requent i symptoms or β-hCG level trends

reect a higher ectopic pregnancy risk (American College o

Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2019c). VS also may be

repeated. Tis serial assessment to reach a diagnosis is balanced

against the rupture risk i the pregnancy is indeed ectopic. Dilation and curettage (D & C) is an option (Barnhart, 2021). It

may give a aster diagnosis but may interrupt a normal IUP.

Beore curettage, a second VS examination may be indicated

and may display new inormative ndings.

As noted, ectopic pregnancies can rupture even at low β-hCG

levels. Tus, serum β-hCG values are usually ollowed until they

lie below the negative-result threshold or the given assay.

Endometrial Findings

In a woman in whom ectopic pregnancy is suspected, VS is

perormed to look or ndings indicative o an IUP or ectopic

FiGURE 12-2 This 7-cm decidual cast was passed by a patientwith a tubal ectopic pregnancy. The cast mirrors the shape of the

endometrial cavity, and each arrow marks the portion of decidua

that lined the cornua.Ectopic Pregnancy 223

CHAPTER 12

pregnancy. During endometrial cavity evaluation, an intrauterine gestational sac is usually visible between 4½ and 5 weeks.

Te yolk sac appears between 5 and 6 weeks, and a etal pole

with cardiac activity is rst detected at 5½ to 6 weeks (Fig. 14-1,

p. 248). With transabdominal sonography, these structures are

visualized slightly later.

In contrast, with ectopic pregnancy, a trilaminar endometrial pattern is characteristic (Fig. 12-3). Its specicity is 94

percent, but with a sensitivity o only 38 percent (Hammoud,

2005). In addition, Moschos and wickler (2008) determined

in women with a PUL at presentation that no normal IUPs had

an endometrial stripe thickness <8 mm.

Anechoic uid collections, which might normally suggest

an early intrauterine gestational sac, may also be seen with

ectopic pregnancy. Tese include pseudogestational sac and

decidual cyst. First, a pseudosac is a uid collection between

the endometrial layers and conorms to the cavity shape (see

Fig. 12-3). I a pseudosac is noted, the risk o ectopic pregnancy is increased (Hill, 1990). Second, a decidual cyst is identied as an anechoic area lying within the endometrium but

remote rom the canal and oten at the endometrial–myometrial

border. Tis may represent early decidual breakdown that precedes cast ormation (Ackerman, 1993b).

Tese two ndings contrast with the intradecidual sign

seen with IUPs. With this sign, the early gestational sac is an

anechoic sac eccentrically located within one o the endometrial stripe layers (Dashesky, 1988). Te American College

o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2020) advises caution

in diagnosing an IUP i a denite yolk sac or embryo is not

seen.

Adnexal Findings

Te sonographic diagnosis o ectopic pregnancy rests on seeing an adnexal mass separate rom the ovary (Fig. 12-4). I

an extrauterine yolk sac, embryo, or etus is identied, ectopic

FiGURE 12-3 Transvaginal sonography of a pseudogestational sac

within the endometrial cavity. Its central location is characteristic

of these anechoic fluid collections. The endometrium is marked

by calipers, and distal to this fluid, the endometrial thickness has a

trilaminar pattern. This pattern is common with ectopic pregnancy.

(Reproduced with permission from Jason McWhirt, ARDMS.)

FiGURE 12-4 Various transvaginal sonographic findings with

ectopic tubal pregnancies. For sonographic diagnosis, an ectopic

mass should be seen in the adnexa separate from the ovary and

may be seen as: (A) a yolk sac (shown here) and/or fetal pole with

or without cardiac activity within an extrauterine sac, (B) an empty

extrauterine sac with a hyperechoic ring, or (C) an inhomogeneous

adnexal mass. In this last image, color Doppler shows a classic “ring

of fire,” which reflects increased vascularity typical of ectopic pregnancies. LT OV = left ovary; SAG LT AD = sagittal left adnexal;

UT = uterus.224 First- and Second-Trimester Pregnancy Loss

Section 5

pregnancy is clearly conrmed. In other cases, a hyperechoic

halo or tubal ring surrounding an anechoic gestational sac is

seen. Alternatively, hemorrhage within the ectopic pregnancy

can orm a solid, complex adnexal mass. Overall, 60 percent

o ectopic pregnancies are a complex mass; 20 percent are a

hyperechoic ring; and 13 percent have an obvious gestational

sac with a yolk sac or embryo (Condous, 2005). Importantly,

not all adnexal masses represent an ectopic pregnancy. In this

case, integration o sonographic ndings with other clinical

inormation is necessary.

Placental blood ow within the periphery o the complex

adnexal mass—the ring o fre—can be seen with application

o color Doppler. A corpus luteum cyst oten displays a similar

vascular pattern, and dierentiation can be challenging.

Hemoperitoneum

In aected women, blood in the peritoneal cavity is most oten

identied using VS (Fig. 12-5). A small amount o peritoneal uid is physiologically normal. However, with hemoperitoneum, anechoic or hypoechoic uid initially collects

in the dependent retrouterine cul-de-sac. It then additionally

surrounds the uterus as blood lls the pelvis. With signicant

intraabdominal hemorrhage, blood will track up the pericolic

gutters to ll Morison pouch near the liver. Free uid in this

pouch typically is not seen until accumulated volumes reach

400 to 600 mL (Branney, 1995; Rodgerson, 2001). Diagnostically, peritoneal uid in conjunction with an adnexal mass and

a positive pregnancy test result are highly predictive o ectopic

pregnancy (Nyberg, 1991). Ascites rom cancer is a notable

mimic.

I sonography is unavailable, culdocentesis is a simple technique and was used commonly in the past. Te cervix is pulled

outward and upward toward the symphysis with a tenaculum,

and a long, 18-gauge needle is inserted through the posterior

vaginal ornix into the retrouterine cul-de-sac. I present, uid

can be aspirated. However, no uid is interpreted only as

unsatisactory entry into the cul-de-sac. Bloody uid or uid

with old clot ragments suggests hemoperitoneum. I the blood

sample clots, it may reect an adjacent blood vessel puncture or

brisk bleeding rom ectopic pregnancy rupture.

■ Serum Progesterone

Although not our practice, this hormone is used by some to

aid ectopic pregnancy diagnosis when serum β-hCG levels and

VS ndings are inconclusive (Stovall, 1992). A single value is

sufcient. From studies, a serum progesterone level <6 ng/mL

(<20 nmol/L) has a pooled specicity o 98 percent to predict a

nonviable pregnancy in women with a PUL (Verhaegen, 2012).

A value >25 ng/mL suggests a live IUP and excludes ectopic

pregnancy with 97-percent sensitivity (Carson, 1993). With

most ectopic pregnancies, progesterone levels range between 10

and 25 ng/mL and thus have limited diagnostic utility (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2019c). Serum

progesterone levels can be used to buttress a clinical impression,

but again they cannot reliably identiy location (Guha, 2014).

■ Endometral Samplng

Several endometrial changes accompany ectopic pregnancy, and

all lack coexistent chorionic villi. Decidual reaction is ound in

42 percent o samples, secretory endometrium in 22 percent, and

prolierative endometrium in 12 percent (Lopez, 1994). Some

recommend that lack o chorionic villi be conrmed by D &

C beore methotrexate treatment is given. Chung and associates

(2011) ound that the presumptive diagnosis o ectopic pregnancy

is inaccurate in 27 percent o cases without histological exclusion

o a spontaneous pregnancy loss. Nevertheless, the risks o D &

C are weighed against the limited maternal risks o methotrexate.

Endometrial biopsy with a Pipelle catheter or endometrial

aspiration was studied as an alternative to surgical curettage

and ound inerior (Barnhart, 2003b; Insogna, 2017). Instead,

rozen section o curettage ragments to identiy products o

conception is accurate in 95 percent o cases (Li, 2014).

FiGURE 12-5 Hemoperitoneum. A. This transvaginal sagittal view of the pelvis shows anechoic fluid initially pooling in the retrouterine

cul-de-sac (**). Large accumulations will also extend into the anterior cul-de-sac (*). B. In this right upper quadrant sonogram, anechoic

fluid is seen in Morison pouch (arrowhead). C = cervix; F = fundus; K = kidney; L = liver. (Reproduced with permission from Dr. Devin

Macias.)Ectopic Pregnancy 225

CHAPTER 12

■ Laparoscopy

Direct visualization o the allopian tubes and pelvis by laparoscopy oers a reliable diagnosis in most cases o suspected ectopic pregnancy. Tis also permits a ready transition to denitive

operative therapy, which is discussed subsequently.

MEDiCAL MANAGEMENT

■ Regmen Optons

For most ectopic pregnancies, medical therapy is preerred, i

easible, to avoid surgical risks. Disqualiying criteria are a ruptured allopian tube and drug contraindications. Other considerations include reasonably close access to emergency care and

a commitment to surveillance laboratory testing.

Medical therapy traditionally involves the antimetabolite

methotrexate (MX). Tis drug is a olic acid antagonist. It

tightly binds to dihydroolate reductase, blocking the reduction o dihydroolate to tetrahydroolate, which is the active

orm o olic acid. As a result, de novo purine and pyrimidine

production is halted, which then arrests DNA, RNA, and protein synthesis. Tus, MX is highly eective against rapidly

prolierating trophoblast. However, gastrointestinal mucosa,

bone marrow, and respiratory epithelium also can be harmed.

o help select suitable candidates, laboratory tests are

obtained. First, MX is renally cleared, and signicant renal

dysunction, reected by an elevated serum creatinine level,

precludes its use. Second, MX can be hepato- and myelotoxic, and CBC and liver unction tests (LFs) help establish

a baseline. Last, blood type and Rh status are determined. All

except blood typing are considered surveillance laboratory tests

and are repeated prior to additional MX doses.

With administration, women are counseled to avoid several

aggravating agents until treatment is completed. Tese are: (1)

olic acid-containing supplements, which can competitively

reduce MX binding to dihydroolate reductase; (2) nonsteroidal antiinammatory drugs, which reduce renal blood ow

and delay drug excretion; (3) alcohol, which can predispose to

concurrent hepatic enzyme elevation; (4) sunlight, which can

provoke MX-related dermatitis; and (5) sexual activity, which

can rupture the ectopic pregnancy (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2019c).

MX is a potent teratogen, and MX embryopathy is notable or cranioacial and skeletal abnormalities and etal-growth

restriction (Nurmohamed, 2011). MX is excreted into breast

milk and may accumulate in neonatal tissues and interere with

neonatal cellular metabolism (American Academy o Pediatrics, 2001; Briggs, 2017). Based on all these ndings, a list o

contraindications and pretherapy laboratory testing is ound in

Table 12-1.

For ease and efcacy, intramuscular MX administration is

used most oten or ectopic pregnancy treatment, and singledose and multidose MX protocols are available. With singledose therapy, the dose is 50 mg/m2 body surace area (BSA),

and BSA can be derived using various Internet-based BSA calculators. At our institution, patients are observed or 30 minutes ollowing MX injection to exclude an adverse reaction.

With the multidose regimen, leucovorin is added to blunt

MX toxicity. Leucovorin is olinic acid and has olic acid

activity. Tus, it allows some purine and pyrimidine synthesis

to buer side eects.

Comparing these two protocols, trade-os are recognized.

Single-dose therapy oers simplicity, less expense, and less

intensive posttherapy monitoring. However, some but not all

studies report a higher success rate or the multidose regimen

(Barnhart, 2003a; Lipscomb, 2005; abatabaii, 2012). Overall,

ectopic tubal pregnancy resolution rates approximate 90 percent

with MX use. At our institution, we use single-dose MX.

TABLE 12-1. Medical Treatment Protocols for Ectopic Pregnancy

■ Patent Selecton

Te best candidate or medical therapy is the woman who

is asymptomatic, motivated, and compliant. With medical

therapy, some classic predictors o success include a low initial

serum β-hCG level, small ectopic pregnancy size, and absent

etal cardiac activity. O these, initial serum β-hCG level is the

best prognostic indicator with single-dose MX. Reported ailure rates are 1.5 percent i the initial serum β-hCG concentration is <1000 mIU/mL; 5.6 percent at 1000 to 2000 mIU/mL;

3.8 percent at 2000 to 5000 mIU/mL; and 14.3 percent or

levels between 5000 and 10,000 mIU/mL (Menon, 2007).

Many early trials also used large size as an exclusion criterion. Lipscomb and colleagues (1998) reported a 93-percent

success rate with single-dose MX when the ectopic mass was

≤3.5 cm. Tis compared with success rates between 87 and 90

percent when the mass was >3.5 cm. Tese authors also ound

ectopic pregnancies measuring ≤4 cm and lacking cardiac

activity to be suitable candidates. Failure rates rise i cardiac

activity is seen, with an 87-percent success rate in such cases.

■ Sde Effects

Tese regimens are associated with minimal laboratory changes

and symptoms, but rarely toxicity may be severe. Kooi and

Kock (1992) reviewed 16 studies and reported that adverse

eects were resolved by 3 to 4 days ater MX was discontinued. Te most requent were liver involvement—12 percent;

stomatitis—6 percent; and gastroenteritis—1 percent. One

woman had bone marrow depression. More commonly, 65 to

75 percent o women given MX will have increasing pain

beginning several days ater therapy. Tought to reect separation o the ectopic pregnancy rom the tubal wall, this pain

generally is mild and relieved by analgesics. In a series o 258

women treated with MX by Lipscomb and colleagues (1999),

20 percent had pain that merited evaluation in a clinic or emergency department to exclude tubal rupture.

Long term, MX treatment does not diminish ovarian

reserve (Ohannessian, 2014). However, ater successul MX

therapy, pregnancy is ideally delayed or at least 3 months,

because this drug may persist in human tissues or months

ater a single dose (Hackmon, 2011). Although data are very

limited, conception beore this waiting period appears reassuring. In one study, 45 women who conceived <6 months

ater MX had similar pregnancy outcomes compared with 80

women who conceived >6 months ater MX (Svirsky, 2009).

■ Survellance

As shown in able 12-1, monitoring single-dose therapy calls

or serum β-hCG determinations at days 4 and 7 ollowing

initial MX injection on day 1. Ater single-dose MX, mean

serum β-hCG levels may rise or all during the rst 4 days

and then should gradually decline. I the level ails to drop by

≥15 percent between days 4 and 7, a second MX dose is recommended. Tis is necessary in 20 percent o women treated

with single-dose therapy (Cohen, 2014). In such cases, a CBC,

creatinine level, and LFs are rechecked. I these surveillance

tests are normal, a second equivalent dose is administered. Te

date o this second injection will become the new day 1, and

the protocol is restarted.

Multidose therapy provides MX (1 mg/kg) treatment

with leucovorin (0.1 mg/kg) therapy on alternating days. Ater

this rst pair o injections, a serum β-hCG concentration is

obtained. Values between days 1 and 3 are anticipated to drop

by ≥15 percent. I not and i surveillance tests are normal,

an additional MX/leucovorin pair is given. A serum β-hCG

level is repeated 2 days later. Up to our doses may be given i

required (Stovall, 1991).

With either dosing regimen, once a decline ≥15 percent is

achieved, weekly serum β-hCG level testing then begins until

values are undetectable. Lipscomb and colleagues (1998) used

single-dose MX to successully treat 287 women and reported

that the average time to resolution—dened as a serum β-hCG

level <15 mIU/mL—was 34 days. Te longest time was 109

days.

SURGiCAL MANAGEMENT

■ Optons

Beore surgery, uture ertility desires are discussed. In women

desiring sterilization, the unaected tube can be ligated or

removed. Tis is done concurrently with salpingectomy or the

ectopic-containing tube.

Laparoscopy is the preerred surgical approach or ectopic

pregnancy unless a woman is hemodynamically unstable. Tis

is supported rst by comparable subsequent uterine pregnancy

rates and tubal patency rates in those undergoing salpingostomy completed either by laparoscopy or by laparotomy (Hajenius, 2007). Second, laparoscopy has lower inection, adhesion,

and thromboembolism risks and aster recovery times than

laparotomy. Moreover, as experience has accrued, cases previously managed by laparotomy—or example, those with hemoperitoneum—can saely be managed laparoscopically by those

with suitable expertise. However, the lowered venous return

and cardiac output associated with pneumoperitoneum must

be actored into the selection o minimally invasive surgery or

a hypovolemic woman.

wo procedures—salpingostomy or salpingectomy—are

options. In the past, some avored salpingostomy to preserve uture ertility. However, two randomized trials compared laparoscopic outcomes between the two procedures in

women with a normal contralateral allopian tube. Te European Surgery in Ectopic Pregnancy (ESEP) study randomized 231 women to salpingectomy and 215 to salpingostomy.

Ater surgery, the subsequent cumulative rates o ongoing

pregnancy by natural conception did not dier signicantly

between groups—56 versus 61 percent, respectively (Mol,

2014). Again, in the DEMEER trial, the subsequent 2-year

rate or achieving an IUP did not dier between groups—64

versus 70 percent, respectively (Fernandez, 2013). However,

or women with an abnormal-appearing contralateral tube, salpingostomy o the ectopic-containing tube may be preerred

i easible to help preserve ertility.

O the two procedures, salpingectomy may be used or

both ruptured and unruptured ectopic pregnancies. With oneEctopic Pregnancy 227

CHAPTER 12

laparoscopic technique, the aected allopian tube is lited and

held with atraumatic grasping orceps. One o several suitable

bipolar grasping devices is placed across the allopian tube at

the uterotubal junction. Once desiccated, the tube is cut rom

its uterine attachment. Te bipolar device is then advanced

across the mesosalpinx to ree the entire tube.

Salpingostomy is typically used to remove a small unruptured pregnancy. A 10- to 15-mm linear incision is made on

the antimesenteric border o the allopian tube and over the

pregnancy. Te products usually will extrude rom the incision. Tese can be careully extracted or can be ushed out

using high-pressure irrigation that more thoroughly removes

the trophoblastic tissue. Small bleeding sites are controlled with

needlepoint electrosurgical coagulation, and the incision is let

unsutured to heal by secondary intention (ulandi, 1991).

With either procedure and ater specimen removal, the pelvis

and abdomen are irrigated and suctioned ree o blood and tissue debris to remove all trophoblastic tissue.

■ Persstent Trophoblast

Ater trophoblast removal during surgery, β-hCG levels usually

all quickly. Persistent trophoblast is rare ollowing salpingectomy but complicates 5 to 15 percent o salpingostomy cases

(Pouly, 1986; Seier, 1993). Incomplete trophoblast removal

can be identied by stable or rising β-hCG levels (Hajenius,

1995). Monitoring approaches are not codied. Weekly measures are reasonable ollowing salpingostomy (Mol, 2008).

Following uncomplicated salpingectomy, we do not repeat

β-hCG levels in women without pain or symptoms o hemoperitoneum.

With stable or increasing β-hCG levels, additional surgical or medical therapy is necessary. In those without evidence

or tubal rupture, standard therapy or persistent trophoblast is

single-dose MX, 50 mg/m2 × BSA. ubal rupture and bleeding require a second surgery.

■ Medcal versus Surgcal Therapy

O options, multidose MX treatment and laparoscopic salpingostomy have been compared in one randomized trial o 100

patients. Te authors ound no dierences or rates o tubal

preservation, primary treatment success, and subsequent ertility (Dias Pereira, 1999; Hajenius, 1997).

For single-dose MX, its efcacy compared with laparoscopic salpingostomy shows conicting results. In one randomized trial, single-dose MX was less successul in pregnancy

resolution, whereas in the other, single-dose MX was equally

eective (Saraj, 1998; Sowter, 2001). Krag Moeller and associates (2009) reported during a median surveillance period o 8.6

years that ectopic-resolution success rates and cumulative spontaneous IUP rates were not signicantly dierent between those

managed by laparoscopic salpingostomy and those treated with

single-dose MX.

Salpingectomy eectively removes the entire conceptus

and yields high resolution rates. It thus outperorms MX in

this regard. Yet, when uture ertility and ectopic pregnancy

recurrence rates are analyzed, both salpingectomy and MX

therapy show comparable results (de Bennetot, 2012; Irani,

2017). In another study, surgery, MX, or expectant management all yielded statistically similar subsequent spontaneous

IUP rates (Demirdag, 2017).

In sum, medical or surgical management oer similar outcomes in women who are hemodynamically stable, have serum

β-hCG concentrations <5000 mIU/mL, and have a small pregnancy with no cardiac activity. Despite lower success rates with

medical therapy or women with larger tubal size, higher serum

β-hCG levels, and etal cardiac activity, medical management

can be oered to the motivated woman who understands the

risks o emergency surgery in the event o treatment ailure.

■ Expectant Management

In select asymptomatic women, observation o a very early

tubal pregnancy that is associated with stable or alling serum

β-hCG levels is reasonable. A commitment to surveillance visits

and relative proximity to emergency care are other saeguards.

Importantly, this diers rom expectant management o a PUL

during its evaluation.

Predictive actors or success include a low initial serum β-

hCG concentration, a signicant drop in levels over 48 hours,

and a sonographic inhomogeneous mass rather than a tubal

halo or other gestational structures. For example, initial values <175 mIU/mL predict spontaneous resolution in 88 to 96

percent o attempts (Elson, 2004; Kirk, 2011). Initial values

<1000 mIU/mL have success rates ranging rom 71 to 92 percent (Jurkovic, 2017; Mavrelos, 2013; Silva, 2015).

With expectant management, subsequent rates o tubal

patency and intrauterine pregnancy are comparable with

surgery (Helmy, 2007). Tat said, compared with the established saety o medical or surgical therapy, the prolonged

surveillance and risks o tubal rupture support the practice

o expectant therapy only in appropriately selected and counseled women.

iNTERSTiTiAL PREGNANCY

■ Dagnoss

An interstitial pregnancy is one that implants within the tubal

segment that lies within the muscular uterine wall (Fig. 12-6).

Incorrectly, they may be called cornual pregnancies, but this

term describes a conception that develops in the rudimentary horn o a uterus with a müllerian anomaly. Risk actors

are similar to others discussed or tubal ectopic pregnancy,

although previous ipsilateral salpingectomy is a specic one

or interstitial pregnancy (Lau, 1999). Undiagnosed interstitial

pregnancies usually rupture ollowing 8 to 16 weeks o amenorrhea, which is later than or more distal tubal pregnancies. Te

myometrium covering the interstitial allopian tube segment

permits greater distention beore rupture. Because o the proximity o these pregnancies to the uterine and ovarian arteries,

hemorrhage can be severe and associated with mortality rates as

high as 2.5 percent (ulandi, 2004).

In many cases, these pregnancies are identied early, but diagnosis can still be challenging. Tese pregnancies sonographically228 First- and Second-Trimester Pregnancy Loss

Section 5

can appear similar to an eccentrically implanted IUP, especially

in a uterus with a müllerian anomaly. Criteria that may aid

dierentiation include: an empty uterus, a gestational sac seen

separate rom the endometrium and >1 cm away rom the

most lateral edge o the uterine cavity, and a thin, <5-mm

myometrial mantle surrounding the sac (imor-ritsch, 1992).

Moreover, an echogenic line, known as the interstitial line sign,

extending rom the gestational sac to the endometrial cavity

most likely represents the interstitial portion o the allopian

tube and is highly sensitive and specic (Ackerman, 1993a). In

unclear cases, three-dimensional (3-D) sonography, magnetic

resonance (MR) imaging, or diagnostic laparoscopy can help

clariy anatomy. Laparoscopically, a myometrial protuberance

is seen to lie lateral to the round ligament and coexists with

normal distal tubes and ovaries.

■ Management

Surgically, either cornual resection or cornuostomy may be per-

ormed via laparotomy or laparoscopy, depending on patient

hemodynamic stability and surgeon expertise. With either

approach, intraoperative intramyometrial vasopressin injection

may limit surgical blood loss. Cornual resection removes the

gestational sac and surrounding cornual myometrium by means

o a wedge excision (Fig. 12-7). Alternatively, cornuostomy

involves incision o the cornual myometrium and suction or

instrument extraction o the pregnancy. Both instances require

layered myometrial closure. β-hCG levels are monitored postoperatively to exclude remnant trophoblast.

With early diagnosis, medical management may be considered.

However, consensus regarding MX regimens is lacking because

o small study numbers. Jermy and coworkers (2004) reported a

94-percent success with systemic MX using a dose o 50 mg/

m2 × BSA. Others employ a traditional multidose MX regimen

(Hiersch, 2014). Direct MX injection into the gestational sac

also oers comparable success (Framarino-dei-Malatesta, 2014).

Last, a uterine artery MX inusion ollowed by uterine artery

embolization (UAE) is termed chemoembolization by some. Tis

combined with systemic MX has shown promise (Krissi, 2014).

Te risk o uterine rupture with subsequent pregnancies

ollowing either medical or surgical management is undened.

Tus, elective cesarean delivery ater 370/7 weeks’ gestation,

which is timed similarly to those with prior at-risk myomectomy, is reasonable (American College o Obstetricians and

Gynecologists, 2021).

Distinct rom interstitial pregnancy, the term angular pregnancy is used by some to describe eccentric implantation near

FiGURE 12-6 Interstitial ectopic pregnancy. A. This parasagittal view using transvaginal sonography shows an empty uterine cavity and a

mass that is cephalad and lateral to the uterine fundus (calipers). B. Intraoperative photograph during laparotomy and before cornual resection of the same ectopic pregnancy. In this frontal view, the bulging right-sided interstitial ectopic pregnancy is lateral to the round ligament

insertion and medial to the isthmic portion of the fallopian tube. (Reproduced with permission from Drs. David Rogers and Elaine Duryea.)

FiGURE 12-7 During cornual resection, the pregnancy, surrounding myometrium, and ipsilateral fallopian tube are excised en

bloc. The incision is angled inward as it is deepened. This creates a

wedge shape into the myometrium, which is then closed in layers

with delayed-absorbable suture. The serosa is closed with subcuticular style suturing. (Reproduced with permission from Hoffman

BL, Hamid CA, Corton MM: Surgeries for benign gynecologic conditions. In Hoffman BL, Schorge JO, Halvorson LM, et al: Williams

Gynecology, 4th ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2020.)Ectopic Pregnancy 229

CHAPTER 12

one cornu but within the endometrial cavity. In one prospective case series o 42 such pregnancies, 80 percent progressed to

a viable age, and abnormal placentation or uterine rupture did

not develop (Bollig, 2020). Tese eccentrically implanted early

IUPs are managed as normal pregnancies at our institution.

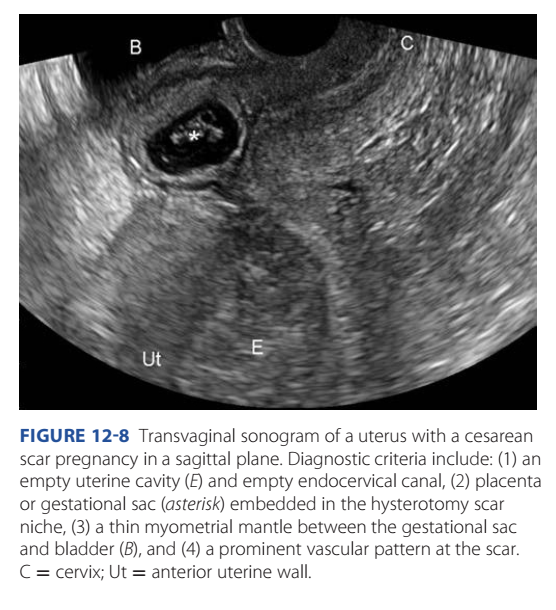

CESAREAN SCAR PREGNANCY

■ Dagnoss

Tis term describes implantation within the myometrium o a

prior cesarean delivery scar. Its incidence approximates 1 case

in 2000 normal pregnancies and has increased along with the

cesarean delivery rate (Rotas, 2006).

Women with symptomatic cesarean scar pregnancy (CSP)

usually present early, and pain and bleeding are common. Still,

up to 40 percent o women are asymptomatic, and the diagnosis

is made during routine sonographic examination (Rotas, 2006).

Sonographic criteria are described in Figure 12-8 (imor-

ritsch, 2012). Further, CSP implantation can be divided into

endogenic and exogenic patterns. Endogenic CSPs implant on

the scar and expand toward the uterine cavity, whereas exogenic

ones implant deeply within the scar niche and grow toward the

bladder or abdominal cavity. In one small study o CSPs that

continued to viability, endogenic CSPs yielded variable obstetric outcomes, whereas all exogenic CSPs underwent hysterectomy with placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) at delivery (Kaelin

Agten, 2017).

Sonographically, dierentiating between an IUP implanted

at the cervicoisthmic junction and a CSP can be difcult. Investigators in one study marked the midpoint o the uterine length

(cervix to undus) in sagittal views. I the center o the gestational sac lay distal to this midpoint, a CSP was diagnosed

(imor-ritsch, 2016). A spontaneous expelling abortus is

another mimic. Color Doppler will show the intense placental

vascularity around a CSP, whereas as the aborting sac is avascular. Moreover, gentle pressure applied to the cervix by the

vaginal probe will ail to move an implanted gestation—a negative sliding sign. Instead, an aborted sac will slide against the

endocervical canal (Jurkovic, 2003). VS is the typical rst-line

imaging tool, but MR imaging is useul or inconclusive cases.

■ Management

Insights into the pathogenesis o CSPs are expanding management options. Namely, growing evidence suggests that some

o these pregnancies will not behave as a typical ectopic pregnancy, and rupture rates are lower. CSPs are thought by some

to be a precursor o PAS (imor-ritsch, 2014). As such, a

signicant percentage o aected pregnancies will progress to

a viable-aged neonate, albeit with the complications associated

with PAS (Calì, 2018; imor-ritsch, 2015b).

Patients may preer to avoid rupture and PAS risks and seek

pregnancy termination. From one literature review, the most

successul operations include: (1) laparoscopic uterine isthmic

resection; (2) transvaginal isthmic resection through an anterior

colpotomy, created similarly to anterior entry during vaginal hysterectomy; (3) UAE, ollowed by D & C with or without hysteroscopy; and (4) hysteroscopic resection (Birch Petersen, 2016;

Wang, 2014). Te Society or Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM)

(2020) considers sonography-guided vacuum aspiration alone, but

not sharp curettage, to be suitable. In some instances, hysterectomy

is required or may be elected in those not desiring uture ertility.

Medical management is an option or those hoping to avoid

surgery. However, compared with surgery, pregnancy resolution rates are more varied and lengthier. In one review, local

MX injection into the gestational sac alone provided a success rate o 60 percent, and systemic plus local MX raised the

rate to nearly 80 percent (Maheux-Lacroix, 2017). Te SMFM

(2020) recommends against systemic MX alone.

With local MX, doses o 1 mg/kg or 50-mg doses have been

described. Prior to local MX, etal death can be induced in

more advanced gestations by potassium chloride (KCL) injection

into the sac (Grechukhina, 2018). One option is 1 mL o 2 mEq/

mL KCL. Also, i associated bleeding complicates medical management, a Foley balloon catheter can be placed and expanded

(imor-ritsch, 2015a). Recently, a novel double-balloon catheter, in which the balloons lie in tandem, has been used with

MX to resolve CSPs (Monteagudo, 2019). Te cephalad balloon is lled within the endometrial cavity to prevent device

expulsion. Te lower balloon is tightly inated to interrupt the

CSP via mechanical pressure and tamponades potential bleeding.

Following conservative treatment, subsequent pregnancies

have good outcomes, but PAS and recurrent CSP are risks (Gao,

2016; Wang, 2015). In one series o 30 CSPs, ve subsequent

pregnancies developed normally, whereas our were recurrent

CSPs (Grechukhina, 2018). Uterine arteriovenous malormations

are a potential long-term complication (imor-ritsch, 2015b).

CSPs have also been expectantly managed. Te Society or

Maternal–Fetal Medicine (2020) recommends against this

practice. Exceptions may be early CSPs with evidence o pregnancy

ailure. One review o 69 patients continuing their gestation ound

that uterine rupture or dehiscence complicated 10 percent o all

FiGURE 12-8 Transvaginal sonogram of a uterus with a cesarean

scar pregnancy in a sagittal plane. Diagnostic criteria include: (1) an

empty uterine cavity (E) and empty endocervical canal, (2) placenta

or gestational sac (asterisk) embedded in the hysterotomy scar

niche, (3) a thin myometrial mantle between the gestational sac

and bladder (B), and (4) a prominent vascular pattern at the scar.

C = cervix; Ut = anterior uterine wall.230 First- and Second-Trimester Pregnancy Loss

Section 5

cases (Calì, 2018). During the rst or second trimester, hysterectomy was perormed in 15 percent. For the 40 patients progressing to the third trimester, 17 had placenta percreta, 23 patients

underwent hysterectomy, and two patients had uterine rupture or

dehiscence. For all trimesters, 60 percent o cases ultimately underwent hysterectomy. More reassuringly, in early pregnancies without cardiac activity, 70 percent had uncomplicated miscarriage,

whereas 30 percent required surgical or medical intervention. O

these early demises, none required hysterectomy.

Women accepting expectant care are ideally well counseled

on these potential obstetric complications. I not prompted by

earlier complications, repeat cesarean delivery is recommended

at 340/7 and 356/7 weeks’ gestation, and this timing recognizes

the PAS and uterine rupture risks associated with CSP. Betamethasone to hasten lung maturity is recommended prior to

delivery (Society or Maternal–Fetal Medicine, 2020).

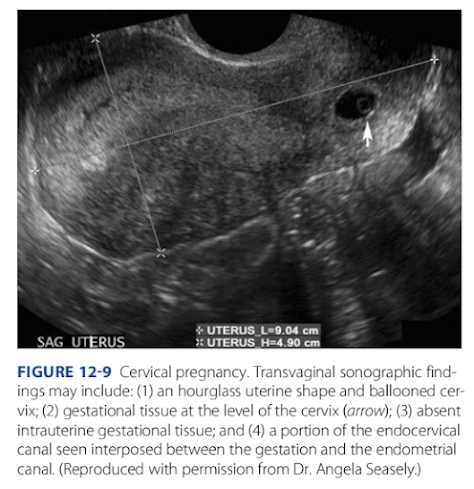

CERViCAL PREGNANCY

■ Dagnoss

Tis rare ectopic pregnancy is dened rst by cervical glands

noted histologically opposite the placental attachment site. Second, all or part o the placenta lies at a level below the entrance

o the uterine vessels or below the peritoneal reection on the

anterior uterus. rophoblast invades the endocervix, and the

pregnancy develops in the brous cervical wall. Risk actors

include AR and prior uterine curettage (Ginsburg, 1994).

Painless vaginal bleeding is reported by 90 percent o women

with a cervical pregnancy, and it can be severe (Ushakov,

1997). As pregnancy progresses, a distended, thin-walled cervix

with a partially dilated external os may be evident. Above the

cervical mass, a slightly enlarged uterine undus is elt. ypical

sonographic ndings are shown and described in Figure 12-9.

In some cases, MR imaging and 3-D VS can aid diagnosis.

At times, cervical ectopic pregnancy can mimic a miscarriage

in transit through the cervix. Similar to CSPs and described in

that section, color Doppler will show the intense vascularity o

cervical implantation, and gentle pressure applied to the cervix

by the vaginal probe will ail to move an implanted gestation—

a negative sliding sign.

■ Management

Cervical pregnancy may be treated medically or surgically.

In many centers, including ours, MX is rst-line therapy in

hemodynamically stable women. O options, single- or multidose systemic MX and dosing ound in able 12-1 are

suitable (Murji, 2015). Alternatively, 50 mg o MX can be

injected directly into the gestational sac (Jeng, 2007; Yamaguchi, 2017). Others describe chemoembolization with MX and

UAE, as described or interstitial pregnancy (p. 228).

With MX regimens, resolution and uterine preservation are achieved or gestations <12 weeks in 91 percent

o cases (Kung, 1997). o select appropriate candidates,

Hung and colleagues (1996) noted higher risks o systemic

MX treatment ailure in those with a gestational age >9

weeks, β-hCG levels >10,000 mIU/mL, crown-rump length

>10 mm, and etal cardiac activity. For this reason, eticidal KCL can be injected into the etus or gestational sac

(Verma, 2009). Notably, during posttherapy surveillance,

sonographic resolution lags ar behind serum β-hCG level

regression (Song, 2009).

Although conservative management is easible or many

women with cervical pregnancies, suction evacuation or hysterectomy may be selected. Moreover, hysterectomy may be

required with bleeding uncontrolled by conservative methods

(Fowler, 2021). During hysterectomy, because o the close proximity o the ureters to the ballooned cervix, urinary tract injury

rates are a concern.

I suction evacuation o the cervix is planned, intraoperative

bleeding may be lessened by preoperative UAE, by intracervical vasopressin injection, or by a cerclage placed at the internal

cervical os to compress eeding vessels (Chen, 2015; Fylstra,

2014; Wang, 2011). Cervical branches o the uterine artery

can eectively be ligated with vaginal placement o hemostatic

cervical sutures on the lateral aspects o the cervix at 3 and

9 o’clock (Bianchi, 2011).

As an adjunct to medical or surgical therapy, UAE has been

described either as a response to bleeding or as a preprocedural

prevention (Hirakawa, 2009; Zakaria, 2011). Also, in the event

o hemorrhage, a 26F Foley catheter with a 30-mL balloon can

be placed intracervically and inated to eect hemostasis by

vessel tamponade and to monitor bloody drainage. Te balloon

remains inated or 24 to 48 hours and is gradually decompressed over a ew days (Ushakov, 1997).

ABDOMiNAL PREGNANCY

■ Dagnoss

Tese rare ectopic pregnancies are dened as an implantation in the peritoneal cavity exclusive o tubal, ovarian, or

FiGURE 12-9 Cervical pregnancy. Transvaginal sonographic findings may include: (1) an hourglass uterine shape and ballooned cervix; (2) gestational tissue at the level of the cervix (arrow); (3) absent

intrauterine gestational tissue; and (4) a portion of the endocervical

canal seen interposed between the gestation and the endometrial

canal. (Reproduced with permission from Dr. Angela Seasely.)Ectopic Pregnancy 231

CHAPTER 12

intraligamentous implantations. Most are thought to ollow

early tubal rupture or tubal abortion with reimplantation.

Clinically, symptoms may be absent or vague. Laboratory

tests are typically uninormative, although maternal serum

alpha-etoprotein levels can be elevated. With later gestations,

abnormal etal positions may be palpated, or the cervix is displaced (Zeck, 2007). Sonographically, clues are a etus or placenta seen eccentrically positioned within the pelvis or separate

rom the uterus; lack o myometrium between the etus and

the maternal anterior abdominal wall or bladder; or bowel

loops surrounding the gestational sac (Allibone, 1981; Chukus,

2015). Oligohydramnios is common but nonspecic. Oten

needed, MR imaging can aid diagnosis and provide placental

inormation.

■ Management

Abdominal pregnancy treatment depends on the gestational

age at diagnosis. Conservative expectant management carries

a maternal risk or sudden, dangerous hemorrhage. Moreover,

Stevens (1993) reported etal malormations and deormations in 20 percent. Tus, we believe that termination generally is indicated once the diagnosis is made. Certainly, beore

24 weeks’ gestation, conservative treatment rarely is justied.

Despite this, some describe waiting until etal viability with

close surveillance (Harirah, 2016).

Principal surgical objectives are delivery o the etus and

careul assessment o placental implantation without provoking hemorrhage. Unnecessary exploration is avoided because

the anatomy is commonly distorted and surrounding areas are

extremely vascular. Importantly, placental removal may precipitate torrential hemorrhage because the normal hemostatic

mechanism o myometrial contraction to constrict hypertrophied blood vessels is lacking. I it is obvious that the placenta

can be saely removed or i the implantation site is already

bleeding, then removal begins immediately. Blood vessels supplying the placenta are ideally ligated rst. For early gestations,

locally injected dilute vasopressin also can be employed.

Some advocate leaving the placenta in place as the lesser o

two evils. It decreases the chance o immediate lie-threatening

hemorrhage, but at the expense o long-term sequelae. Placental embolization may play a role prior to or ollowing etal

extraction (Frischhertz, 2019; Marcelin, 2018). I let in the

abdominal cavity, the placenta can orm abscesses, adhesions,

intestinal or ureteral obstruction, and wound dehiscence (Bergstrom, 1998; Martin, 1988). In many o these cases, surgical

removal becomes inevitable. I the placenta is let, its involution can be monitored using serum β-hCG levels and color

Doppler sonography or MR imaging (France, 1980; Martin,

1990). Placental unction usually declines rapidly. Te placenta

is eventually resorbed, but this can take months or years with

advanced gestations (Valenzano, 2003).

I the placenta is let, postoperative MX is oten given to

hasten involution. Accelerated placental destruction with accumulation o necrotic tissue ollows (Deng, 2017). Inection

with abscess ormation can be a complication (Rahman, 1982).

Similar to persistent trophoblastic tissue, early gestations may

benet most (Ansong, 2019).

OVARiAN PREGNANCY

Ectopic implantation o the ertilized egg in the ovary is rare

and is diagnosed i our clinical criteria are met. Tese were

outlined by Spiegelberg (1878): (1) the ipsilateral tube is intact

and distinct rom the ovary; (2) the ectopic pregnancy occupies

the ovary; (3) the ectopic pregnancy is connected by the uteroovarian ligament to the uterus; and (4) ovarian tissue can be

demonstrated histologically amid the placental tissue. Risk actors are similar to those or tubal pregnancies, but AR or IUD

ailure are prominent (Zhu, 2014). Presenting complaints and

ndings mirror those or tubal ectopic pregnancy. Although the

ovary can accommodate the expanding pregnancy more easily

than the allopian tube, rupture at an early stage is the usual

consequence (Melcer, 2016).

Sonographically, an internal anechoic area is surrounded by a

wide echogenic ring, which in turn is surrounded by ovarian cortex (Comstock, 2005). In one review o 49 cases, the diagnosis

was not be made until surgery, and many cases were presumed to

be a tubal ectopic pregnancy (Choi, 2011). Moreover, at surgery,

an early, unrecognized ovarian pregnancy may instead be considered and managed as a hemorrhagic corpus luteum.

Evidence-based management accrues mainly rom case

reports (Hassan, 2012). Classically, management or ovarian

pregnancies has been surgical. Selection o laparoscopy or laparotomy are inuenced by gestational age, hemoperitoneum,

and hemodynamic status. Small lesions can be managed by

ovarian wedge resection or cystectomy, whereas larger lesions

require oophorectomy (Elwell, 2015; Melcer, 2015). With

conservative surgery, β-hCG levels should be monitored to

exclude remnant trophoblast.

HETEROTOPiC PREGNANCY

Tis pairing o an IUP and an ectopically located pregnancy

is rare, and the most common dyad is an IUP and an ampullary tubal pregnancy. Te natural incidence o these heterotopic

pregnancies approximates 1 case per 30,000 pregnancies (Reece,

1983). However, with AR, their incidence is higher and is

9 cases in 10,000 pregnancies (Perkins, 2015). Initial clinical

symptoms usually reect those rom the ectopic. Because an

IUP is seen sonographically and the ectopic pregnancy may not

be visualized, rates o rupture are higher in heterotopic pregnancy (Dendas, 2017).

In patients wishing to preserve the IUP, management initially is dictated by bleeding. In those with hemorrhage, treatment o the ectopic pregnancy is surgical. Depending on the

ectopic location, resection or suction aspiration is the most

common method (Wu, 2018). O note, adjunctive UAE and

vasopressin and their eects on uterine blood ow are less

desirable or the ongoing IUP. With a rare comorbid ovarian

ectopic pregnancy, early excision o the corpus luteum merits

progesterone supplementation (Chap. 66, p. 1170).

In those without signicant bleeding, medical steps to disrupt the ectopic pregnancy typically involve gestational-sac

injection o KCl or o hyperosmolar glucose. Tis may be ollowed by later aspiration evacuation o the ectopic gestation.

Because o toxicity to the IUP, MX is avoided.232 First- and Second-Trimester Pregnancy Loss

Section 5

With ongoing pregnancy, adverse neonatal outcome rates are

not appreciably elevated (Clayton, 2007). However, initial sonographic surveillance o etal growth seems reasonable. Route o

ultimate delivery is inuenced mainly by myometrial integrity

ollowing ectopic treatment (Dendas, 2017; OuYang, 2014).

Nhận xét

Đăng nhận xét