Chapter 13 Endometriosis of Nongynecologic Organs and Extrapelvic Sites

GENERAL PRINCIPLES

Definition

Endometriosis is the presence of ectopic endometrial glands and stroma. Disease involvement is diverse and may be superficially limited or deeply infiltrative into organ systems such as the gastrointestinal and urinary tracts and the respiratory and musculoskeletal systems.

Differential Diagnosis

■ Benign neoplasm

■ Malignant neoplasm

■ Overactive bladder

■ Painful bladder syndrome

■ Irritable bowel syndrome

■ Inflammatory bowel disease

■ Myofascial pain

Nonoperative Management

■ Nonoperative management includes hormonal suppression with oral contraceptive pills, progestin therapy, or Levonorgestrol secreting IUD, gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, and off-label use of aromatase inhibitors. These treatments may provide symptomatic pain relief and reduce the size of lesions. However, even with optimal medical therapy many patients remain symptomatic due to fibrosis and infiltrating disease.

Physical therapy and pain management procedures may also alleviate symptoms. Refractory pain and the uncertain neoplasm etiology lead many patients to undergo surgical resection and histologic confirmation of nonmalignant endometriosis.

■ Bladder endometriosis warrants a trial of medical management. If there is a concern for obstructive uropathy, nephrostomy tubes and ureteral stents may also be used. Surgery is indicated for symptomatic patients who suffer from extrinsic obstruction, have contraindications to medical management, or who would benefit from ureteroneocystotomy.

■ Bowel obstruction, ureteral stenosis, and pneumothorax caused by endometriosis implants typically require urgent surgical management in addition to palliative procedures (nasogastric tube, ureteral stent placement, and chest tube), concomitant medical management, and monitoring of electrolytes, kidney, and respiratory function.

■ Postoperatively, we recommend continued hormonal suppression, no matter the disease location, and continue this therapy long term.

■ One cautionary note: Asymptomatic patients with histologically confirmed endometriosis and extrapelvic or nongynecologic disease do not require surgical treatment and may be medically managed. Those with advanced disease may be followed with imaging if there is concern for advancing invasive disease.

■ Conversely, a symptomatic patient without histologically confirmed endometriosis and imaging suggestive of endometriosis lesions must undergo a laparoscopic tissue biopsy at the very minimum to confirm the endometriosis diagnosis. The patient’s quality of life, comorbid conditions, and lesion’s mass effect should all be considered prior to surgical resection. It is crucial to confirm the endometriosis diagnosis by tissue pathology to avoid inappropriate medical management of a malignant neoplasm.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTICS

■ Tumor markers such as CA125 are often elevated in patients with endometriomas. Therefore, we do not recommend this serum testing for a patient with known deep endometriosis extending more than 5 mm into the peritoneum and lesions with characteristic appearance of extraperitoneal endometriosis.

■ Perform preoperative cystoscopy to assess bladder mucosal involvement if suspicious for this by the patient’s history.

■ Small-bowel endoscopy and colonoscopy rarely reveal transmural or mucosal endometriosis but may be useful to evaluate for differential bowel diseases, suspected malignancy, or bowel strictures secondary to endometriosis.

■ Transvaginal and abdominal ultrasound can detect rectosigmoid and bladder endometriosis. This imaging requires experienced sonographers and a high level of radiographic expertise.

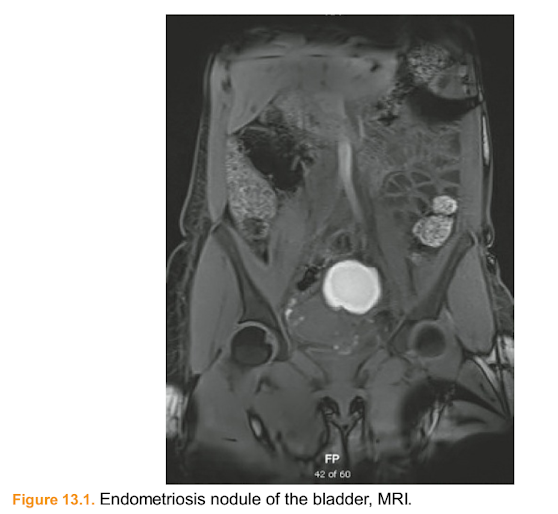

■ Computed tomography (CT) is only useful for pelvic mass evaluation and ureteral obstruction but it is not useful for pelvic soft tissue evaluation. Instead, we prefer Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), with enterography, for preoperative soft tissue evaluation (Figs. 13.1 to 13.4).

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

■ Patients with anterior abdominal wall disease can be examined easily in the office. Patient discomfort and habitus, however, may limit the utility of this examination.

■ A rectovaginal examination should be performed to determine the presence of tissue thickening, masses, and nodularity. If the patient can tolerate a bimanual examination, this can also yield useful information such as a fixed, retroverted uterus, irregularity or tenderness of the posterior cul-desac and vaginal fornices.

■ Occasionally, a speculum examination reveals pigmented endometriosis lesions that may be easily biopsied. Lesions that are deep to the vaginal mucosa should not be aggressively biopsied in the office as they may communicate with the rectum.

Figure 13.1. Endometriosis nodule of the bladder, MRI.

■ We strongly advise referring these patients to a tertiary center with surgical experts experienced at managing nongynecologic endometriosis in an interdisciplinary fashion. Although endometriosis may present in anatomic locations that are surgically unfamiliar to gynecologists, it is important not to treat this benign, albeit tenacious, disease as an oncologic subset. Doing so places the patient at risk of decreased fertility,unnecessary intervention, and increased surgical risks. Surgical treatment is peppered with a myriad of known complications, many of which can be fatal if mismanaged. Even after successful surgical treatment, patients often require ongoing medical and ancillary treatments to abate the sequelae of their disease.

Figure 13.2. Right obstructive hydronephrosis, CT urogram.

Figure 13.3. Obliterated cul-de-sac and spiculated endometriosis lesion, rectocervical disease, MRI.

■ The comprehensive medical and surgical management of patients sufferingfrom extraperitoneal endometriosis should only be undertaken at large centers with the personnel and resources capable of providing complete care for the patient.

■ Interdisciplinary treatment teams may include surgeons and physicians from urology, colorectal/general surgery, gastroenterology, plastic surgery, cardiothoracic surgery, physical therapy, and pain management.

■ The goal of surgical extraperitoneal endometriosis management is to remove endometriosis and fibrosis and to restore the organ’s function. Hysterectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy may also be considered depending on the age and desired future fertility of the patient.

Figure 13.4. Rectrocervical endometriosis, MRI.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Urinary System—Bladder and Ureter

■ Approximately 0.3% to 6% of endometriosis cases have urinary tract involvement. Most commonly, endometriosis affects the bladder (84%), ureter (15%), kidney (4%), and urethra (4%).

■ Symptoms include hematuria, vesical or suprapubic pain, dysuria, urinary frequency, and back pain that may be constant or cyclical especially at the time of menses.

■ Imaging may reveal focal thickening of the bladder wall, edema, or a mass lesion. Cystoscopy confirms the absence or presence of mucosal involvement.

■ Extrinsic ureteral compression is usually due to peritoneal fibrosis. Intrinsic ureteral compression is often caused by endometriotic implants on the muscularis of the ureter.

■ Ureteral resection is often necessary if hydronephrosis exists.

Gastrointestinal System—Bowel and Rectum■ Rectocervical or bowel endometriosis is present in 5% to 12% of endometriosis cases and usually coexists with other endometriosis lesions. The most common bowel sites are the rectum and sigmoid colon, followed by the appendix and small bowel/ileum.

■ Symptoms include dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, bloating, constipation, diarrhea, dyschezia, and hematochezia.

■ Based on anatomic location, bowel endometriosis can be divided into two subsets: rectocervical disease and disease affecting the bowel wall proximal to the rectosigmoid.

■ Rectocervical disease often requires uterosacral ligament excision and/or posterior cul-de-sac adhesiolysis.

■ Rectal nodule or local excision may confer equal pain relief compared to segmental rectal resection and with less postoperative gastrointestinal side effects.

■ In general, bowel resection for endometriosis depends on the lesion size, depth of invasion, and the percentage of circumference involved. The smallest resection that eradicates the diseased area and maintains functional anatomy is preferred.

■ Perform a partial bowel excision (disc excision) if there is a:

■ unifocal lesion less than 3 cm.

■ lesion that involves less than 60% of the circumference of the rectum or sigmoid wall.

■ Perform a segmental bowel resection if there is:

■ deep invasion of the muscularis, or

■ a lesion larger than 3 cm or multiple nodules.

■ The posterior vaginal fornix and pelvic sidewall require concomitant dissection and endometriosis resection.

Musculoskeletal System

■ Iatrogenic endometriosis seeding occurs when the endometrium is breached during surgical procedures such as cesarean delivery. At that time, endometrial tissue can escape from the uterine cavity and implant along the fascia, muscle, subcutaneous fat, and other surfaces exposed during the surgery. The prevention, pathogenesis, and optimal treatment of musculoskeletal and abdominal wall endometriosis are unknown. Future areas for study include recurrence rates, optimal resection margins, and surgical techniques to decrease recurrence.Figure 13.5. Abdominal wall endometriosis, CT abd pelvis.

■ Symptoms: Cyclic or constant abdominal pain often with a palpable abdominal wall mass near a prior incision or trocar site.

■ Seventy-five percent of patients report perimenstrual pain and have a history of cesarean delivery.

■ Patients usually present in their mid-30s and their last surgery may be several months to years prior to clinical presentation. The mean mass size is 4 cm and is often misdiagnosed as an incisional hernia or granuloma.

■ Perform CT to characterize the lesion (Figs. 13.5 and 13.6A,B).

Other Distant Sites

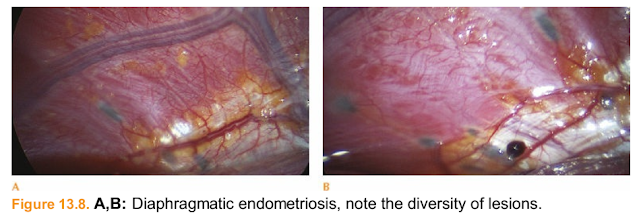

The enigmatic, and at times obstinate, nature of endometriosis can also affect distant sites and organs such as the diaphragm, lung, nervous and lymphatic systems. As with the pelvic counterparts, management of distant endometriosis should focus on minimizing the clinical sequelae of the disease and restoring/preserving organ function. The value of experienced, interdisciplinary surgical and medical management to yield optimal patient care is underscored.

■ Symptoms of thoracic endometriosis include right-sided catamenial pneumothorax hemoptysis, chest pain, and dyspnea. Some patients are asymptomatic and do not require treatment. Co-management with an experienced interdisciplinary team that includes gynecologic, thoracic, vascular surgeons and neurosurgeons for disease resection in the respective distant organs is recommended (Figs. 13.7 and 13.8).

Positioning

■ Patients should be placed in low lithotomy with leg stirrups (refer to Chapter 5 for laparoscopic patient positioning details). Alternatively, the patient may lie supine. Please refer to Chapter 8 for positioning details foran abdominal approach.

Approach

Preoperative Prophylaxis

■ We recommend all patients receive venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis commensurate with their VTE risk. Administer antibiotics within 60 minutes before the procedure and re-dose for major blood loss or prolonged procedures at intervals equal to 2.5 times the half-life of the antibiotic.

Figure 13.6. A: Left rectus muscle seen anteriorly with spiculated endometriosis invasions into the bladder serosa, coronal, noncontrast MRI. (For intraoperative images, see Tech Fig. 13.38.) B: Left rectus muscle with poorly demarcated bladder interface, sagittal T2-weighted MRI. (For intraoperative images, see Tech Fig. 13.38.)

Figure 13.7. Right hydropneumothorax with liver herniation thru diaphragm due to

endometriosis, coronal view MRI.

Figure 13.8. A,B: Diaphragmatic endometriosis, note the diversity of lesions.

■ Urinary tract and abdominal wall procedures:

■ Administer 2 g Cefazolin IV for patient less than 120 kg and 3 g for

patients greater than 120 kg. Redose approximately every 4 hours during

the procedure.

■ Gastrointestinal tract:

■ Given variations in bowel preparation and antibiotic preferences, we recommend discussing this preoperatively with your colorectal surgeon.

Procedures and Techniques: Urinary Tract Endometriosis Resection (Video 13.1) Place a uterine manipulator of choice and a three-way Foley catheter into the bladder to allow for bladder instillation if needed throughout the surgery. SeeChapter 5 for basic setup and entry for laparoscopy.

Superficial bladder peritoneum resection

■ Grasp and sharply incise the normal bladder peritoneum (Tech Fig. 13.1).

■ Dissect the loose areolar tissue and underlying structures off the peritoneum and around the endometriosis implant (Tech Fig. 13.2).

■ Then excise the implant sharply or with radiofrequency or plasma energy.

■ Perform cystoscopy to confirm ureteral patency and lack of mucosal involvement.

Tech Figure 13.1. Superficial peritoneal bladder lesion.

Tech Figure 13.2. Bluntly dissect loose areolar tissue.

Deep endometriosis resection involving the bladder muscularis

■ An understanding of bladder anatomy is important for safe and efficient surgery (Tech Fig. 13.3).

■ Begin laterally and sharply dissect the underlying nonfibrotic tissue away from the implant(s) (Tech Figs. 13.4 and 13.5).

Tech Figure 13.3. Normal bladder anatomy and layers.

Tech Figure 13.4. Obliterated vesicouterine space with infiltrating endometriosis into thebladder muscularis.

Tech Figure 13.5. Sharp excision of fibrotic adhesions.

■ Grasp the abnormal tissue and press “toward the lesion” and not away (Tech

Fig. 13.6).

■ Identify the correct dissection plane: the nodule’s interface to normal, healthy

bladder tissue.

■ Push the uterus cephalad with a uterine manipulator to facilitate this planedissection.

■ Once healthy tissue is encountered, bluntly dissect the tissue away from the fibrosis to minimize the loss of normal tissue and anatomy distortion (Tech Fig. 13.7).

Tech Figure 13.6. Bladder resection technique and lesion isolation.

Tech Figure 13.7. Operative technique: proper plane dissection limits destruction to healthy tissue.■ Excise the nodule and the affected bladder peritoneum and bladder muscularis en bloc (Tech Fig. 13.8).

■ The implant and the affected bladder muscularis may be excised without entering the bladder lumen (Tech Fig. 13.9A,B).

Tech Figure 13.8. Enbloc resection of endometriosis nodule, bladder peritoneum, and muscularis.

Tech Figure 13.9. A: Endometriosis implant and bladder muscularis (in Allis grasper). B: Final view of restored vesicouterine space not requiring cystotomy.

Deep endometriosis resection involving the bladder dome mucosa

■ First, perform cystoscopy and place bilateral ureteral stents (Tech Fig. 13.10A,B).

■ Create a cystotomy at the dome (Tech Fig. 13.11).

■ Identify the intravesicular Foley catheter. Note the distance of the ureteral stents and ureteral orifices from the mucosal lesion (Tech Fig. 13.12A,B).

■ Perform a partial cystectomy by circumscribing and then excising the transmural lesion sharply (Tech Fig. 13.13A,B).

Tech Figure 13.10. Cystoscopic views. A: Bladder mucosa with posterior> endometrial lesion. B: Double left ureter with separate stents.

Tech Figure 13.11. Cystotomy at bladder dome.Tech Figure 13.12. A: Note the endometriosis nodule that extends from the dome to the posterior bladder wall, the two left ureteral stents, and the foley catheter. B: Complete intravesicular view. Note the distance between the orifices to the lesion.

Tech Figure 13.13. A: Circumscribe the transmural bladder lesion. B: Excise the nodule sharply and complete the partial cystectomy.

■ Close the bladder defect in two layers.

■ Re-approximate the bladder mucosa with a 3-0 delayed absorbable running suture such as polyglactin 910 (Tech Fig. 13.14A).

■ Imbricate the bladder muscularis with 2-0 delayed absorbable suture.

■ Retrograde fill the bladder with sterile solution and laparoscopically inspect the peritoneal cavity and bladder to ensure a watertight closure (Tech Fig. 13.14B).

■ Place a Jackson–Pratt drain in the pelvis through a laparoscopic port site.

■ Perform a cystogram 1 week postoperatively to confirm there is no extravasation from the bladder and remove the Foley catheter.

Tech Figure 13.14. A: First layer of bladder closure. B: Imbricate and backfill the bladder.

Ureterolysis, ureter evaluation, and ureter procedures

■ When endometriosis and fibrosis over lie the ureter, perform ureteral dissection and adhesiolysis (Tech Fig. 13.15A,B).

■ Incise the peritoneum at the level of the pelvic brim (Tech Fig. 13.16).

■ Perform blunt dissection of the connective tissue.

■ Identify and isolate the ureter on the medial leaf of the broad ligament.

■ Continue dissection to the level of the cardinal ligament.

■ If endometriosis invades the adventitia, incise the adventitia while preserving the muscularis (Tech Fig. 13.17).

■ Visually inspect the condition and functionality of the ureter (Tech Fig. 13.18).

■ Identify any stricture, dilation, and note adequate perfusion and vermiculation.

Tech Figure 13.15. Peritoneal endometriosis over (A) the right ureter and (B) the left ureter.

Tech Figure 13.16. Ureterolysis from the left pelvic brim.

Tech Figure 13.17. Ureter layers.

Tech Figure 13.18. Left pelvic sidewall dissection.

Ureteroneocystostomy allows for resection of the diseased distal ureter and reimplantation into the bladder

■ The ureter is transected proximal to the stricture, spatulated, and directly anastomosed with the aid of a double-J stent. A psoas hitch or Boari flap may be needed to reduce tension on the anastomosis if proximal ureteral mobilization alone is inadequate. At the conclusion of the procedure, place a surgical intraperitoneal drain and maintain a Foley catheter.

■ Approximately 1 week postoperatively remove the Foley catheter.

■ Four to 6 weeks postoperatively perform a cystoscopy and retrograde pylogram to confirm adequate healing and to remove the double-J stents. Alternatively, the stents may be removed and a CT urogram obtained to confirm ureteral patency.

Tech Figure 13.19. Simplified ureteroureteral anastomosis: spatulate and suture the segments over a stent.

Ureteroureteral anastomosis with double-J stenting can be considered if:

■ The stenosis or obstructive disease is located in the middle or upper third of the ureter and there is sufficient ureteral length.

■ The contralateral ureter is confirmed to be functional (Tech Fig. 13.19).

■ At the conclusion of the procedure, place a surgical intraperitoneal drain.

■ Four to 6 weeks postoperatively perform a cystoscopy and retrograde pylogram to confirm adequate healing and remove the double-J stents.

Procedures and Techniques: Gastrointestinal Tract Endometriosis Resection (Video 13.2)

Rectocervical endometriosis resection

■ Identify anatomic landmarks such as the ureters and uterosacral ligaments bilaterally. Assess the extent of organ involvement (Tech Figs. 13.20 and 13.21).

■ Develop the pararectal spaces with blunt dissection and then sharp dissection once fibrosis and endometriosis are encountered.

■ The pararectal space is defined laterally by the internal iliac vessels, medially by the rectum and ureter, posteriorly by the sacrum, and anteriorly by the cardinal ligaments and uterine arteries (Tech Fig. 13.22).

Tech Figure 13.20. Obliterated cul-de-sac.Tech Figure 13.21. Obliterated cul-de-sac with endometriosis rectal nodule.

Tech Figure 13.22. On the left, pararectal space dissection. In the midline, cul-de-sac dissection.

■ Dissect the rectum from the posterior uterus and vagina.

■ This is facilitated by applying caudad pressure on the posterior vaginal fornix with a vaginal sponge stick. To push the rectum toward the sacrum place a reusable end-to-end anastomotic (EEA) sizer into the rectum (Tech Figs. 13.23 and 13.24).

■ Excise the endometriotic plaque and adjacent fibrosis.

■ While viewing the lesion laparoscopically, we recommend manual palpation of the vaginal fornices, and posterior vaginal wall to verify complete excision of diseased tissue.

■ If vaginectomy is inherent to the procedure take care to suture the vaginal tissue in a transverse fashion to avoid vaginal stenosis or foreshortening of the vagina.

■ Assess the anterior rectal wall and rectum and colon to determine if further discoid or segmental resection is necessary.

■ Restore normal anatomy (Tech Fig. 13.25).

Tech Figure 13.23. Sponge stick in vagina to identify the posterior fornix area (compare to Tech Fig. 13.22).

Tech Figure 13.24. Rectal probe during dissection directed to the patient’s left to identify the right pararectal space.

Tech Figure 13.25. Final appearance: restored cul-de-sac anatomy. Bowel endometriosis focal resection

■ An understanding of colon and rectum anatomy is important for safe and efficient surgery (Tech Fig. 13.26).

■ Evaluate the lesion size, penetration depth, and circumferential involvement.

■ Lesions limited to the serosa can be shaved by sharply excising the lesion with scissors or electrosurgery.

■ Grasp the lesion and excise only the fibrotic and endometriotic tissue.

■ Inspect the integrity of the bowel for muscularis invasion.

■ Imbricate the serosa as needed taking care not to stenose the underlying layers and bowel lumen.

■ Then assess bowel integrity.

■ Perform intraoperative endoscopy or air insufflation with intraperitoneal water instillation to inspect anastomotic integrity and to confirm a watertight closure.

Tech Figure 13.26. Layers of the rectum.

■ Full-thickness discoid resection can be performed if:

■ The lesion penetrates deeper than the superficial serosa and involves less than 60% of the bowel circumference.

■ Place a rectal probe or sizer in the rectum to aid in bowel dissection. The sizer also acts as a backstop when sharply excising the full-thickness lesion. Grasp the lesion and excise only the fibrotic and endometriotic tissue (Tech Fig. 13.27).

Tech Figure 13.27. Full-thickness (discoid) resection with visible EEA sizer.Repair the enterotomy with a two-layer closure

■ The suture line should be placed perpendicular to the lumen of the bowel (Tech Fig. 13.28).

■ Use 3-0 delayed absorbable, interrupted sutures to close the defect with full thickness, incorporating all bowel wall layers.

■ Imbricate the second layer with 2-0 or 3-0 delayed absorbable or permanent interrupted sutures, also known as a Lembert stitch (Tech Fig. 13.29).

■ Assess bowel integrity (Tech Fig. 13.30).

Tech Figure 13.28. The first of two-layer enterotomy closure with suture line perpendicular to the bowel lumen.

Tech Figure 13.29. Lembert stitch

Tech Figure 13.30. Watertight enterotomy closure.

Bowel endometriosis segmental resection

■ Identify the segment of colon and/or rectum to be resected with involved disease.

■ Mobilize its pertinent retroperitoneal attachments.

■ Select the proximal and distal margins of the segment and divided with a linear stapler taking into account tissue thickness when choosing stapler height (TechFig. 13.31).

■ Achieve hemostasis of major vascular structures with suture ligation and divide the remaining mesentery with an advanced energy source.

Tech Figure 13.31. Resected bowel segment.

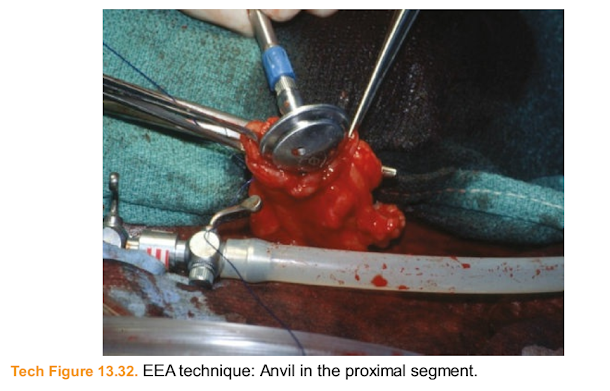

■ Complete the reconstruction by means of hand-sewn, linear-stapled, or circularstapled techniques.

■ For an EEA technique, insert the anvil into the proximal limb (Tech Fig. 13.32).

■ Place a monofilament suture in a purse-string configuration and tie it to secure the anvil in place (Tech Fig. 13.33).

Tech Figure 13.32. EEA technique: Anvil in the proximal segment.

Tech Figure 13.33. EEA technique: Anvil secured with purse-string suture.

■ Insert the stapler handle into the distal limb.

■ This is accomplished transanally for lower anastomoses, including colorectal or coloanal, or through the cut end of bowel for a more proximal anastomosis, such as an ileocolic anastomosis.

■ Mate the stapler and anvil (Tech Fig. 13.34).

■ Engage the device to create the circular stapled anastomosis.

■ For more proximal anastomoses, close the stapler insertion site with a linear stapler in the standard fashion. Some surgeons prefer to oversew the staple lines.

■ Assess bowel integrity as described above.

Tech Figure 13.34. EEA technique: Mate stapler and anvil.Procedures and Techniques: Musculoskeletal/Anterior

Abdominal Wall

Abdominal wall endometriosis resection

■ While the patient is awake and lying supine, mark the site of pain and palpable mass with the patient’s assistance in the operating room.

■ Induce anesthesia and perform routine sterile surgical preparations.

■ Inject local anesthetic and, if possible, use the prior surgical incision.

■ Once the scar is visually identified, palpate the lesion to identify its borders.

■ Grasp the mass and perform adhesiolysis of the surrounding fibrotic tissue with a monopolar instrument (Tech Fig. 13.35).

■ Frequently palpate the mass and surrounding tissue to ensure no residual endometriosis remains in situ.

■ If the fascia is entered, mark the location with a delayed absorbable suture for easy re-approximation and identification.

■ Continue with meticulous dissection until the lesion is completely excised (Tech Fig. 13.36).

■ The nodule contains a variety of glandular, fatty, and fibrotic tissues (Tech Fig. 13.37).

■ Re-approximate the fascia with delayed absorbable suture.

■ Place interrupted sutures to re-approximate the dead space if the subcutaneous tissue measures greater than 3 cm.

■ The dermis may be re-approximated with either staples or suture.

Tech Figure 13.35. Grasp and excise the endometriosis.

Tech Figure 13.36. Endometriosis nodule in towel clamp (left) and suture marking the

fascia entry.

Tech Figure 13.37. Abdominal wall endometriosis nodule, bivalve.

Advanced abdominal wall techniques

■ When the endometrioma encompasses a large surface area or invades multiple layers through the muscle, fascia, and into underlying viscous (Tech Fig. 13.38), advanced techniques to close the abdominal wall may be required.

■ A component separation allows for medialization of the rectus fascia, which results in tension-free re-approximation of the fascia.

■ Dissect and identify the insertion of the external oblique muscle fascia into the rectus. Incise the aponeurosis of the external oblique fascia. This can beperformed from the costal margin down to the pubic symphysis.

■ Re-approximate the anterior rectus sheath at midline with interrupted delayed absorbable suture.

■ If mesh is needed, select the appropriate type and size and secure it with interrupted sutures taking care not to injure the underlying bowel and organs.

The mesh may be placed in an intraperitoneal location, with closure of the fascia above it. Alternatively, the mesh may be placed in a retro-rectus position. This requires opening of the posterior rectus sheath and dissection of this plane laterally. Once developed, the posterior rectus sheath is closed with absorbable suture. The mesh is inserted and secured with suture. Then, close the anterior fascia (Tech Figs. 13.39 and 13.40).

■ Place drains if needed.

■ Re-approximate the skin with suture or staples.

Tech Figure 13.38. Rectus muscle, fascia, subcutaneous tissue, and abdominal endometrioma adherent to bladder. A 31-year-old G5P4 presented with 10 months of severe cyclic pain. Her history was significant for a cesarean delivery 5 years prior. MRI revealed an infiltrative mass that measured 10 cm × 6 cm × 4 cm in the distal rectus abdominis muscles. The mass had notable spiculated margins and a halo of edema with increased T2 signaling that crossed midline and was just below her previous Pfannensteil incision (Fig. 13.6A,B). The mass encompassed 60% of the left rectus muscle and stretched from just above the pubic symphysis to above her umbilicus.

Tech Figure 13.39. Mesh for large anterior abdominal wall defect, retracted caudad.

Tech Figure 13.40. Large abdominal endometrioma resection required advanced closure techniques and mesh.

PEARLS AND PITFALLS

Consider a preoperative biopsy to confirm the diagnosis of benign extraperitoneal endometriosis prior to a respective surgery.

Clearly outline the goals of the extirpative surgery (relieve obstruction, mass excision, pain reduction), complications, possibility of recurrence, and postoperative chronic treatments. Even in emergent cases, poor preoperative counseling and collaborative patient goal setting may undermine long-term outcomes despite excellent surgical technique.

Always dissect and identify the ureters before initiating adhesiolysis or excisional procedures.

Bladder and rectocervical endometriosis is complicated by dense scarring and aberrant anatomy. Begin dissections lateral to the lesions in the perivesical and perirectal spaces, respectively.

Repair ureterostomy with interrupted 4-0 polydioxanone sutures and place a ureteral stent.

Extensive debridement of the ureteral adventitia may result in devascularization of the ureter.

Visual and frequent tactile evaluation of the musculoskeletal mass will aid in adhesiolysis and dissection

Large fascial defects may require mesh, component separation, and abdominal wall reconstruction. Preoperative imaging and surgical team planning are important.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

Urinary Tract Endometriosis Resection

■ Remove the surgical drain once its output is minimal. If there is any concern for urinary collection from the pelvic drain send the fluid for creatinine evaluation before the drain is removed. Gastrointestinal Tract Endometriosis Resection

■ Clear diet is started on postoperative day 1 and is advanced ad lib. IV patient-controlled analgesia is typically used until the patient is transitioned to oral medications.

Musculoskeletal/Anterior Abdominal Wall

■ As with all extraperitoneal endometriosis, regardless of their location, we recommend continued, hormonal suppression in the immediate postoperative state and continue this therapy for long term. If the resectionsite is large, the patient may require overnight admission for several days and may benefit from postoperative rehabilitation and physical therapy.

Postoperative care should be individualized and focus on early ambulation and improved functionality.

OUTCOMES

Urinary Tract Endometriosis Resection

■ A large comparison of ureterolysis, ureteroureteral anastomosis, ureteroneocystotomy, and bladder resection outcomes has yet to be performed. This could be due to several reasons including the belief that ureteral endometriosis is a separate entity from bladder endometriosis. In general, urinary tract endometriosis surgery is well tolerated with few complications.

Gastrointestinal Tract Endometriosis Resection

■ Most excisional rectovaginal endometriosis case series report excellent short-term pain relief in 70% to 80% of patients. At 1 year postoperatively, however, approximately 50% of the patients required hormonal or analgesic treatment. A quarter of the patients undergo a subsequent operation.

Musculoskeletal/Anterior Abdominal Wall

■ There are several case reports and reviews of abdominal wall endometriomas in cesarean section scars and laparoscopic trocar sites. As mentioned earlier, the recurrence rates, optimal resection margins, and surgical techniques to decrease recurrence are unknown and warrant further investigation.

COMPLICATIONS

Urinary Tract Endometriosis Resection

■ Urinary tract complications include ureteral injury, fistula, and leakage.

Gastrointestinal Tract Endometriosis Resection

■ Gastrointestinal tract complications include bladder denervation, rectovaginal fistula, anastomotic leak, and pelvic abscess. In general, the larger the resection, the higher the complication rate. The major complications from radical endometriosis resection are listed in Table 13.1.

Table 13.1 Major Complications from Radical Rectocervical EndometriosisSurgery

Musculoskeletal/Anterior Abdominal Wall

■ Case reports of malignant transformation are rare and the frequency is unknown. The major postoperative complications from abdominal wall resection include hematoma, seroma, hernia, and surgical site infection.

Nhận xét

Đăng nhận xét