Cesarean Delivery and Peripartum Hysterectomy

BS. Nguyễn Hồng Anh

In the United States, the cesarean delivery rate rose most dramatically rom 4.5 percent in 1970 to 32.9 percent in 2009. Te rate has since plateaued and was 31.9 percent in 2018 (Martin, 2019).

Some indications or perorming cesarean delivery are shown in Table 30-1. More than 85 percent o these operations are per- ormed or our reasons—prior cesarean delivery, labor dystocia or arrest, etal jeopardy, or abnormal etal presentation. Te latter three compose the main indications or primary cesarean delivery (Barber, 2011; Boyle, 2013). Eorts to lower these rates are outlined in Safe Prevention of the Primary Cesarean Delivery by the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2019b).

Reasons or persistently elevated cesarean rates are not completely understood, but some explanations include the ollowing:

1. Women are having ewer children, thus, a greater percentage o births are among nulliparas, who are at increased risk or cesarean delivery.

2. Average maternal age is rising, and older women, especially older nulliparas, have a higher cesarean delivery risk.

3. Electronic etal monitoring use is widespread and associated with a higher cesarean delivery rate compared with intermittent etal heart rate auscultation.

4. Most breech etuses are now delivered by cesarean.

5. Te requency o operative vaginal delivery has declined.

6. Obesity, which is a cesarean delivery risk, has reached epidemic proportions.

7. Rates o cesarean delivery in women with preeclampsia have risen, whereas labor induction rates or these patients have declined.

8. Te vaginal birth ater cesarean (VBAC) rate has decreased rom a high o 28 percent in 1996 to 13.3 percent in 2018 (Martin, 2019).

9. Assisted reproductive technology is more widely used and is linked with greater cesarean delivery rates (Luke, 2019).

DEFINITIONS

Cesarean delivery denes the birth o a etus by laparotomy and then hysterotomy. Tis denition is not applied to removal o the etus rom the abdominal cavity in the case o uterine rupture or o abdominal pregnancy. Rarely, hysterotomy is perormed in a woman who has just died or in whom death is expected soon—postmortem or perimortem cesarean delivery (Chap. 50, p. 897).

In some cases, abdominal hysterectomy is indicated ater delivery. When perormed at the time o cesarean delivery, the operation is cesarean hysterectomy. I done shortly ater vaginal delivery, it is postpartum hysterectomy. Peripartum hysterectomy is a broader term that combines these two. In most cases, total hysterectomy is perormed and removes the uterine body and cervix. Supracervical hysterectomy is selected less oten and removes only the uterine body. With either, adnexa are not usually and multiparous populations. Dening women who would be at highest long-term risk or pregnancy-related pelvic oor disorders might allow accurate delivery counseling (Jelovsek, 2018).

■ Neonatal Morbidity

Cesarean delivery is associated with a lower rate o etal trauma (Linder, 2013; Moczygemba, 2010). Alexander and colleagues (2006) ound that etal injury complicated 1 percent o cesarean deliveries. Skin laceration was most common, but others included cephalohematoma, clavicular racture, brachial plexopathy, skull racture, and acial nerve palsy. Cesarean deliveries ollowing a ailed operative vaginal delivery attempt had the highest injury rate. Te lowest rate—0.5 percent— occurred in the elective cesarean delivery group. Tat said, Worley and associates (2009) ound that approximately a third o women who were delivered at Parkland Hospital entered spontaneous labor at term, and 96 percent o these delivered vaginally without adverse neonatal outcomes.

■ Cesarean Delivery on Maternal Request

Some women request elective cesarean delivery. Data regarding the true incidence o cesarean delivery on maternal request (CDMR) are poor. An older estimate in the United States was 5 percent (Declercq, 2005). Reasons or the request include protection o pelvic oor support, convenience, ear o childbirth, and reduced risk o etal injury. One retrospective study o more than 66,000 Chinese parturients compared outcomes o those who elected planned vaginal birth or requested primary cesarean delivery (Liu, 2015). Short-term serious maternal morbidity and neonatal mortality rates were similar. For the newborns, rates o birth trauma, inection, and hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy were low in both groups but statistically lower with cesarean delivery. Respiratory distress syndrome rates were greater in the CDMR cohort. A smaller study comparing these two routes o delivery support these ndings (Larsson, 2011). Te debate surrounding CDMR includes two medical points: the concept o inormed ree choice by the woman, and the autonomy o the physician in oering CDMR. o address this, the National Institutes o Health (2006) held a State-o- the-Science Conerence on Cesarean Delivery on Maternal

Request. Notably, most o the maternal and neonatal outcomes examined had insufcient data to permit recommendations. Indeed, one o the main conclusions o the conerence was that more high-quality research is needed to ully evaluate the issue. Guidelines rom the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2020a) note that CDMR should not be perormed beore 39 weeks’ gestation. It is ideally avoided in women desiring several children because o the earlier-described morbidity rom accruing cesarean operations.

PATIENT PREPARATION

■ Delivery Availability

No nationally recognized standard o care currently dictates the acceptable time interval to begin cesarean delivery. Previously, a 30-minute decision-to-incision interval was recommended. However, Bloom and colleagues (2006) evaluated nearly 3000 cesarean deliveries perormed or emergency indications. Tey reported that ailure to achieve a cesarean delivery decision-toincision time <30 minutes was not associated with a negative neonatal outcome. A subsequent systematic review echoed this nding (olcher, 2014). Despite this, when aced with an acute, catastrophic deterioration in etal condition, cesarean delivery usually is indicated as rapidly as possible, and thus purposeul delays are inappropriate. Te American Academy o Pediatrics and the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2017) recommend that acilities giving obstetrical care should have the ability to initiate cesarean delivery in a time rame that best incorporates maternal and etal risks and benets.

■ Informed Consent

Inormed consent is a process and not merely a medical document. Te consenting conversation should enhance a woman’s awareness o her diagnosis and contain a discussion o medical and surgical care alternatives, procedure goals and limitations, and operative risks. For women with a prior cesarean delivery, the option o a trial o labor should be included or suitable candidates. For those desiring permanent sterilization or intrauterine device (IUD) insertion, consenting or these can be completed concurrently (Chaps. 38 and 39, pp. 665 and 684).

An inormed patient may decline a particular recommended intervention, and a woman’s decision-making autonomy must be respected. In the medical record, providers should document the reasons or reusal and should note that the intervention’s value and the health consequences o not proceeding with it have been explained.

For Jehovah’s Witnesses, inormed consent discussions regarding blood products ideally begin early in pregnancy. Acceptable blood products vary widely among individual women, and a preoperative checklist o approved products allows superior preparation (Hubbard, 2015). In general, red cells, white cells, platelets, and plasma are considered primary blood components and are declined. However, certain clotting actors or cell ractions may be acceptable (Lawson, 2015).

Beore and ater surgery, iron, olate, and, i necessary, erythropoietin are accepted agents to help maximize hemoglobin levels. Perioperatively, phlebotomy is limited, and pediatric collection tubes are preerable. Intraoperative options include prompt treatment o atony to limit blood loss and use o topical hemostatic agents, tranexamic acid, and desmopressin to promote clot ormation. Red blood cell salvage can provide autologous donation. Normovolemic hemodilution and controlled hypotensive or hypothermic anesthesia can limit red cell losses. o minimize uncontrolled vessel bleeding, uterine artery embolization, occlusive vascular balloons, and other options are described in Chapter 44 (p. 779) (Scharman, 2017).

■ Timing of Scheduled Cesarean Delivery

With elective delivery beore 39 completed weeks, adverse neonatal sequelae rom neonatal immaturity are appreciable (ita, 2009). o avoid these, assurance o etal maturity beore scheduled elective surgery is essential. Supporting criteria include corroborative ultrasound measurements obtained prior to 20 weeks’ gestation, etal heart tones heard or the past 30 weeks, and passage o 36 weeks since an initial positive pregnancy test result (American Academy o Pediatrics, 2017).

■ Preoperative Care

Current perioperative care is guided by evidence-based enhanced recovery ater surgery (ERAS) recommendations. Among these, solid ood intake is stopped at least 6 hours beore the procedure. Uncomplicated patients may consume moderate amounts o clear liquids up to 2 hours beore surgery (American Society o Anesthesiologists, 2016). Bowel preparation is not recommended (Wilson, 2018). Te woman scheduled or cesarean delivery typically is admitted the day o surgery and evaluated by the obstetrical and anesthesia teams. Recently perormed hematocrit and indirect Coombs test are reviewed. I the latter is positive, compatible blood availability must be ensured.

Regional analgesia is preerred or cesarean delivery. o minimize the lung injury risk rom rare aspiration, gastric acid is ideally buered. An oral antacid is consumed shortly beore regional analgesia or induction o general anesthesia. One example is Bicitra, 30 mL orally in a single dose. Tis can be coupled with an intravenous (IV) dose o an H2-receptor antagonist, which also raises gastric pH (Wilson, 2018).

Once the woman is supine, a wedge beneath the right hip and lower back creates a let lateral tilt to aid venous return and avoid hypotension. Data are insufcient to determine the value o etal monitoring beore scheduled cesarean delivery in women without risk actors. Our practice is to obtain a 5-minute tracing prior to elective cases. At minimum, etal heart sounds should be documented in the operating room prior to surgery.

O urther preparations, hair removal at the surgical site does not lower surgical site inection (SSI) rates (Kowalski, 2016). However, i hair is obscuring, it is removed the day o surgery by clipping, which is associated with ewer SSIs than shaving (anner, 2011). Chemical depilation the night beore surgery compared with clipping has similar SSI rates (Leebvre, 2015). An electrosurgical grounding pad is placed near the surgical incision and typically on the lateral thigh. At Parkland Hospital, we typically insert an indwelling bladder catheter to collapse the bladder away rom the hysterotomy incision, to avert urinary retention secondary to regional analgesia, and to allow accurate postoperative urine measurement. Small studies show that catheterization may be withheld in hemodynamically stable women. Catheter-related discomort can be avoided, but urinary tract inection rates are not lower (Abdel-Aleem, 2014).

Te risk o VE is increased with pregnancy. In the United States in 2014, women with cesarean delivery had a VE rate o 8 per 10,000, which almost doubled the rate or those with vaginal birth (Abe, 2019). Accordingly, or all women not already receiving thromboprophylaxis, the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2020c) recommends initiation o pneumatic compression stockings beore cesarean delivery. Tese are usually discontinued once the woman ambulates. Consensus varies among organizations, and the American College o Chest Physicians suggests only early ambulation or women without risk actors who are undergoing cesarean delivery (Bates, 2012). For women already receiving prophylaxis or those with increased risk actors, they support escalation o prophylaxis. Last, the Royal College o Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2015) is the most conservative and suggest pharmacological prophylaxis or the largest proportion o patients. Tese various methods and recommendations are discussed in Chapter 55 (p. 989).

Some women scheduled or cesarean delivery have a comorbidity that requires specic management in anticipation o surgery. Among others, these include insulin-requiring diabetes, coagulopathy or thrombophilia, chronic corticosteroid use, and signicant reactive airway disease. Surgical preparations are discussed in the respective chapters covering these topics.

■ Infection Prevention

Antibiotic Prophylaxis

Cesarean delivery is considered a clean contaminated case, and postoperative ebrile morbidity is common. Numerous trials show that a single dose o an antibiotic given at the time o cesarean delivery signicantly decreases inectious morbidity (Smaill, 2014). Although more obvious or women in active labor who then require cesarean delivery, this practice also pertains to gravidas undergoing elective surgery. Depending on drug allergies, most recommend a single IV dose o a β-lactam antibiotic—either a cephalosporin or extended-spectrum penicillin. A 1-g dose o ceazolin (Ance) is an efcacious and costeective choice. Additional doses are considered in cases with blood loss >1500 mL or with duration longer than 3 hours.

Recommendations or a 2- or 3-g ceazolin dose in obese parturients are conicting (Ahmadzia, 2015; Maggio, 2015; Swank, 2015; Young, 2015). Te Centers or Disease Control and Prevention recommends a 2-g dose or weights ≥80 kg and 3 g or those ≥120 kg (Berríos-orres, 2017). Te American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2020d) recognizes either dose as suitable or women ≥80 kg. One pharmacokinetic analysis in obese women showed sufcient tissue levels with a 2-g dose or cesarean deliveries lasting 1.5 hours. Authors recommended consideration or redosing in obese women i surgeries were longer (Grupper, 2017).

Evidence also supports extending the antibiotic spectrum (Markwei, 2021; ita, 2008). One large randomized trial added azithromycin, 500 mg IV, to standard prophylaxis prior to cesarean delivery or women in labor or with ruptured membranes (ita, 2016). Rates o SSIs and endometritis were signi- icantly lower in the extended-spectrum group compared with those in the standard prophylaxis cohort.

In pregnant women with a history o inection with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a single, 15-mg/ kg dose o vancomycin can be added to the standard prophylaxis. Decolonization plays a limited role but may be considered prior to a planned cesarean delivery in women with known MRSA colonization (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2020d). Signicant β-lactam allergy maniests as anaphylaxis, angioedema, respiratory distress, or urticaria. Tis merits prophylaxis with a single, 900-mg IV dose o clindamycin combined with a weight-based, 5-mg/kg dose o an aminoglycoside as an alternative. Te 900-mg clindamycin dose is also used or obese patients. Some studies link higher SSI rates to regimens that lack a β-lactam (Wilhelm, 2020). Antepartum penicillin-allergy evaluation by a specialist may redene the signicance o the patient’s prior reaction. Advantageously, this clarication may remove an allergy label and expanded options (Wolson, 2021).

Antibiotic administration beore surgical incision lowers postoperative inection rates without adverse neonatal eects compared with drug administration ater umbilical cord clamping (Mackeen, 2014b; Sullivan, 2007). Prophylaxis is ideally administered within the 60 minutes prior to the start o planned cesarean delivery. For emergent delivery, antibiotics are given as soon as easible.

Preoperative preparation o the abdominal wall skin immediately prior to surgery can help prevent SSIs. Chlorhexidinealcohol or povidone-iodine solutions are suitable, but data avor chlorhexidine (Hadiati, 2020; olcher, 2019). However, adding a wiping o the skin with chlorhexidine the night beore surgery was no better than placebo (Stone, 2020). Once abdominal preparation is completed and dry, surgical drapes cover the patient. One type has a cut-out window in the lower abdomen that is surrounded by an adhesive border. Others are adhesive incisional drapes, in which the skin and plastic drape must be incised together. Te latter may slightly raise SSI rates (Eckler, 2019; Hadiati, 2020).

Although not our practice, preoperative vaginal cleansing with a 1-percent povidone-iodine scrub lowered endometritis and SSI rates in some studies (Haas, 2020; Roeckner, 2019). With povidone allergy, 4-percent chlorhexidine gluconate solution is an alternative. Last, some early evidence may support extending oral antibiotic prophylaxis or 48 hours postcesarean in obese women to lower SSIs (Valent, 2017). Antibiotic prophylaxis against inective endocarditis is not recommended or most cardiac conditions. Exceptions are women with repaired or unrepaired cyanotic heart disease, prosthetic valves, or both. Prior inective endocarditis or cardiac transplantation with resulting valve regurgitation are others (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2020d). Drug inusion is 30 to 60 minutes prior to expected delivery (able 52-9, p. 935). Cesarean inection prophylaxis regimens also serve as appropriate endocarditis coverage.

Other Preventions

Glycemic control in diabetics lowers wound inection rates and is emphasized in Chapter 60 (p. 1068). Smoking is another modiable risk (Avila, 2012). Intraoperative normothermia lowers wound inection rates in general surgery cases (Balki, 2020; Berríos-orres, 2017). Tis tenet is logically extrapolated to cesarean delivery (Caughey, 2018). In children delivered by cesarean, some evidence shows higher asthma and allergy rates (Kristensen, 2016). Gut microbiome dierences between vaginal and cesarean birth groups are a suggested cause (Shao, 2019). With the hope to improve neonatal microbiota, swabbing the newborn mouth with a gauze that was incubated in the maternal vagina 1 hour beore surgery has been described in preliminary studies. However, the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2019c) does not encourage this practice due to ew data and the potential or transmission o harmul organisms.

■ Surgical Safety

Te Joint Commission (2020) describes a protocol to prevent surgical errors. For cesarean delivery, all relevant documents are veried immediately beore surgery, and a “time out” is completed. Te “time out” requires attention o the entire team to conrm that the patient, site, and procedure are correct. Important discussions also include introduction o the patient-care team members, verication o prophylactic antibiotics, estimation o procedure length, and communication o anticipated complications. Additionally, requests or special instrumentation should be addressed preoperatively to prevent potential patient compromise and intraoperative delays.

Surgical res are a specic saety ocus. As prevention, surgeons ideally assess the re risk at the procedure’s start, allow adequate drying o alcohol-based skin antiseptics, and keep ignition sources o the patient or drapes when not in use (Food and Drug Administration, 2018; Wol, 2013).

An instrument, sponge, and needle count beore and ater surgery is essential. Moreover, active communication during surgery should clearly convey items added to the operative eld. At surgery completion, i counts are not reconciled, portable radiographic imaging or retained objects is done.

CESAREAN DELIVERY TECHNIQUE

■ Laparotomy

As with all surgery, a clear understanding of relevant anatomy is essential (Chap. 2, p. 12). For entry into the abdomen, a suprapubic transverse incision or a midline vertical one is chosen or cesarean delivery. Suitable transverse incisions are Pfannenstiel or Maylard incisions, and the Pfannenstiel type is selected most frequently.

Transverse incisions follow Langer lines of skin tension, and thus exert less stress on the closed wound. Compared with vertical ones, Pfannenstiel incisions offer superior cosmesis and lower incisional hernia rates. The Pfannenstiel incision, however, is often discouraged for cases in which a large operating space is essential or in which access to the upper abdomen may be needed. With transverse incisions, because of the layers created during incision of the internal and external oblique aponeuroses, purulent fluid can collect between these. Therefore, some avor a midline vertical incision for cases with high infection risks. Emergent entry is typically faster with vertical incision during primary and repeat cesarean delivery (Wylie, 2010). Last, neurovascular structures, which include the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves and superficial and inferior epigastric vessels, are often encountered with transverse incisions. Logically, bleeding, wound hematoma, and neurological disruption may more frequently complicate these incisions compared with vertical ones. The best incision for the morbidly obese parturient is unclear (Smid, 2016). Our preference for women with morbid obesity is a periumbilical midline vertical incision (Chap. 51, p. 909).

The Maylard incision differs mainly from the Pfannenstiel in that the rectus abdominis muscle bellies and their investing rectus sheath are transected horizontally to widen the operating space. It is technically more difficult due to required muscle cutting and ligation of the inferior epigastric arteries, which lie laterally to these muscle bellies.

Once access is gained, metal handheld retractors provide exposure for hysterotomy. One metaanalysis with nearly 1700 women showed no lowering of postcesarean SSI rates with a disposable plastic barrier retractor (Alexis-O) (Waring, 2018).

FIGURE 30-1 The loose peritoneum above the bladder reflection is grasped with forceps and incised with Metzenbaum scissors

Transverse Incisions

With the Pfannenstiel incision, the skin and subcutaneous tissue are incised using a low, transverse, slightly curvilinear incision. This is made at the pubic hairline, which is typically 3 cm above the superior border of the symphysis pubis. Te incision is extended laterally to accommodate delivery—12 to 15 cm is typical.

Sharp dissection is continued through the subcutaneous layer to the fascia. The superficial epigastric vessels can usually be identified halfway between the skin and fascia, several centimeters from the midline, and these are coagulated. The fascia is then incised sharply at the midline. The anterior abdominal fascia is typically composed of two visible layers, the aponeurosis from the external oblique muscle and a fused layer containing aponeuroses of the internal oblique and transverse abdominis muscles. Ideally, the two layers are individually incised during lateral extension of the fascial incision. The inferior epigastric vessels usually lie outside the lateral border of the rectus abdominis muscle and beneath the fused aponeuroses of the internal oblique and transverse abdominis muscles. Thus, although infrequently required, further lateral extension of the fascial incision may encounter these vessels. In this case, vessels ideally are identified and coagulated or ligated to prevent bleeding and vessel retraction.

Once the fascia is incised, the inferior fascial edge is grasped with Kocher clamps and elevated by an assistant as the operator separates the fascial sheath from the underlying rectus abdominis muscle either bluntly or sharply until the superior border of the symphysis pubis is reached. Next, the superior fascial edge is grasped and again, separation of fascia from the rectus muscle is completed.

Blood vessels coursing between the sheath and muscles are clamped, cut, and ligated, or they are coagulated with an electrosurgery blade. Meticulous hemostasis is imperative to lower rates of incisional hematoma and infection. The fascial separation progresses cephalad and laterally to create a semicircular area above the transverse incision with a radius of approximately 8 cm. This will vary depending on fetal size. The rectus abdominis and pyramidalis muscles are separated in the midline to expose the transversalis fascia and peritoneum.

The transversalis fascia and preperitoneal fat are bluntly dissected away to reach the underlying peritoneum. The peritoneum near the upper end of the incision is opened carefully, either bluntly or by elevating it with two hemostats placed approximately 2 cm apart. This upper site lowers cystotomy risks. The tented fold of peritoneum between the clamps is examined and palpated to ensure that omentum, bowel, or bladder is not adjacent. The peritoneum is then incised. As the incision is extended cephalad above the arcuate line, the transverse fibers of the posterior rectus sheath are seen and are cut along with the peritoneum. The peritoneal incision is then extended downward to just above the peritoneal reflection over the bladder. Importantly, in women with prior intraabdominal surgery, including cesarean delivery, omentum or bowel may be adhered to the undersurface of the peritoneum. In women with obstructed labor, the bladder may be pushed remarkably cephalad.

Midline Vertical Incision

This incision begins 2 to 3 cm above the superior margin of the symphysis. It should be sufficiently long to allow fetal delivery, and 12 to 15 cm is typical. Sharp or electrosurgical blade dissection through the subcutaneous layers ultimately exposes the anterior rectus sheath. A small opening is made sharply with scalpel in the upper half of the linea alba. Placement here helps avoid potential cystotomy. Index and middle fingers are placed beneath the fascia, and the fascial incision is extended first superiorly and then inferiorly with scissors. Midline separation of the rectus muscles and pyramidalis muscles and peritoneal entry are similar to those just described for the Pfannenstiel incision.

■ Hysterotomy

Most often, the lower uterine segment is incised transversely as described by Kerr in 1921. Occasionally, vertical incision confined solely to the lower uterine segment may be elected (Krönig, 1912). In contrast, a classical incision begins as a low vertical incision, which is then extended cephalad into the active portion of the uterine corpus. Last, a fundal or even posterior uterine incision may be selected for cases with placenta accreta syndrome.

FIGURE 30-2 This peritoneal edge is elevated and incised laterally.

Low Transverse Cesarean Incision

For most cesarean deliveries, this incision is preferred. Compared with a classical incision, it repairs easily, causes less incision-site bleeding, and promotes less bowel or omentum adherence to the myometrial incision. Located in the inactive segment, it is also less likely to rupture during a subsequent pregnancy.

Before hysterotomy, the surgeon palpates the fundus to identify degrees of uterine rotation. The uterus may be rotated so that one round ligament is more anterior and closer to the midline (Chap. 3, p. 46). In such cases, the uterus can be manually reoriented and held to permit centering of the incision. This avoids incision extension into and laceration of the adjacent uterine artery. A moist sponge may be used to pack protruding bowel away from the operative field.

The reflection of peritoneum at the upper margin of the bladder and overlying the lower uterine segment is grasped in the midline with forceps and incised transversely with scissors (Fig. 30-1). Following this initial incision, scissors are inserted between peritoneum and lower-uterine-segment myometrium. Open scissors are pushed laterally from the midline on each side.

This transverse peritoneal incision extends almost the full length of the lower uterine segment. As the lateral margin on each side is approached, the scissors are directed slightly cephalad (Fig. 30-2).

The lower edge of peritoneum is elevated, and the bladder is gently separated from the underlying lower uterine segment with blunt or sharp dissection within this vesicouterine space (Fig. 30-3). This bladder flap creation effectively moves the bladder away from the planned hysterotomy site. It also helps prevent bladder laceration if an unintended inferior hysterotomy extension occurs during fetal delivery. If dense adhesions complicate vesicouterine space dissection, sharp dissection is preferred. I unclear, the bladder and its upper border can be identified by distending or “back filling” it with fluid instilled through a Foley catheter (Saaqib, 2020). In general, this caudad separation of bladder does not exceed 5 cm and usually is less. However, in instances in which cesarean hysterectomy is planned or anticipated, extended caudad bladder dissection is recommended to aid total hysterectomy and decrease the risk of cystotomy.

Some surgeons do not create a bladder flap. The main advantage is a shorter skin incision-to delivery time. However, data supporting this practice are currently limited (O’Neill, 2014). Uterine Incision. The uterus is entered through the lower uterine segment. Digital palpation to find the physiological border between firmer upper segment myometrium and the more flexible lower segment can guide placement. This is often at the level of the bladder flap incision.

For women with advanced or complete cervical dilation, the hysterotomy is placed relatively higher. Failure to adjust increases the risk of lateral extension of the incision into the uterine arteries. It may also lead to incision of the cervix or vagina rather than the lower uterine segment. Such incisions into the cervix distort postoperative cervical anatomy.

The uterus can be incised by various techniques. Each is initiated by using a scalpel to transversely incise the exposed lower uterine segment for 1 to 2 cm in the midline (Fig. 30-4). Repetitive shallow strokes help avoid fetal laceration. As the myometrium thins, a fingertip can then bluntly enter the uterine cavity.

FIGURE 30-3 Cross section shows blunt dissection of the bladder off the uterus to expose the lower uterine segment

Once the uterus is entered, the hysterotomy is lengthened by simply spreading the incision, using lateral and slightly upward pressure applied with each index finger (Fig. 30-5). Instead, some evidence supports widening the lower-uterine-segment incision by pulling with fingers in a cephalocaudad direction to help lower hysterotomy extension rates (Morales, 2019; Xodo, 2016).

The goal is to create an incision sufficiently wide to deliver the presenting fetal part yet avoid overextending the incision. Extensions usually tear downward into the lower uterine segment or laterally into the uterine vessels. Extensive inferior tears may include the cervix or vagina. Risk factors for extensions include occiput posterior fetal head position, primary cesarean delivery, and advanced first-stage or second-stage labor (de la orre, 2006; Karavani, 2020). Specific maneuvers to ameliorate this last high-risk setting are discussed in the next section.

Alternatively, if the lower uterine segment is thick and unyielding, cutting laterally and then slightly upward with bandage scissors will lengthen the incision. Importantly, when scissors are used, the index and middle fingers of the nondominant hand are insinuated beneath the myometrium and above fetal parts to help avert fetal laceration. Comparing blunt and sharp expansion of the initial uterine incision, blunt stretch is associated with fewer unintended incision extensions, shorter operative time, and less blood loss. However, the rates of infection and need for transfusion do not differ (Asıcıoğlu, 2014; Saad, 2014).

During hysterotomy creation, if the placenta lies in the incision line, it must be either detached or incised. Placental function is thereby compromised, and thus delivery is expedited.

At times, a low transverse hysterotomy is selected but provides inadequate room for delivery. In such instances, one corner of the hysterotomy incision is extended cephalad into the contractile portion of the myometrium—a J incision. If this is completed bilaterally, a U incision is formed. Last, some prefer to extend in the midline—a T incision. As expected, these have been linked with higher intraoperative blood loss (Boyle, 1996; Patterson, 2002). J-, U-, and T-incisions extend into the contractile portion, and a subsequent trial of labor after cesarean (TOLAC) is more likely to be complicated by uterine rupture. Similarly, from limited data, inferior hysterotomy extensions also are associated with higher rupture rates, and in our practice these preclude TOLAC (Goldarb, 2011). The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2015) notes insufficient evidence to support the general safety of TOLAC in women with a prior significant uterine extension and cautions for decisions to be individualized. Last, a prior classical incision, described later, or a fundal incision substantially raises the rupture risk during subsequent TOLAC. Thus, following a primary cesarean delivery complicated by these exceptional incision types, a conversation disclosing these events and their significance should ensue with the patient and are carefully described in the operative report.

FIGURE 30-4 The myometrium is incised with shallow strokes to avoid cutting the fetal head

FIGURE 30-5 After entering the uterine cavity, the incision is extended laterally with fingers or with bandage scissors (inset).Delivery of the Fetus. With a cephalic presentation, a hand is slipped into the uterine cavity between the symphysis and fetal head. The head is elevated gently with the fingers and palm through the incision. Once the head enters the incision, delivery may be aided by modest fundal pressure (Fig. 30-6). After a long labor with cephalopelvic disproportion, the fetal head may be tightly wedged in the birth canal. This situation raises the risk of hysterotomy extension, of associated blood loss, and of fetal skull fracture. First, a “push” method may be used. With this, upward pressure exerted by a hand in the vagina by an assistant will help to dislodge the head and push it cephalad. If this is anticipated, a patient in frog-leg position may allow easier vaginal access.

Second, as an alternative, a “pull” method grasps the fetal legs and brings them through the hysterotomy. The fetus is then delivered as one would complete a breech extraction. Support for this latter approach comes from small randomized trials and retrospective cohort studies (Berhan, 2014; Jeve, 2016).

The main advantage appears to be lower uterine extension rates. Another pull method attempts to free the head by placing a palm on each fetal shoulder and gently elevating them. Last, a least-common method uses a “fetal pillow.” This is a distensible intravaginal balloon that is positioned below the head and then inflated to elevate the fetal head. Evidence for its superiority to the push method is limited and conflicting (Sacre, 2021; Seal, 2016).

FIGURE 30-7 To place the first forceps blade, the operator’s palm is slipped beneath the head. It is guided along the palm to ultimately lie across the fetal malar and lower parietal bone as in vaginal forceps application.

Conversely, in women without labor, the fetal head may be unmolded and lack a leading cephalic point. Te round head may be difcult to lit through the uterine incision in a relatively thick lower segment that is unattenuated by labor. In such instances, either orceps or a vacuum device may be used to deliver the etal head. For this, the etal head is manually grasped and turned to an occiput transverse position. In this example, the head is let O (LO) position. wo or more ngers o the right hand are introduced inside the hysterotomy and behind the etal head (Fig. 30-7). Fingers o the let hand grasp the handle o the orceps. Te blade’s toe is gently introduced between the hand and etal head. It is curved inward between the etal head and the palmar surace o the ngers.

FIGURE 30-8 A. To apply the second blade, the operator’s hand is inserted into the posterolateral aspect of the hysterotomy. The forceps blade is slipped inward across the palm. This hand then guides the blade to overlie the upper malar and parietal bones. B. Once positioned, the handles are interlocked. Slight upward and outward traction is used to lift the head through the incision.For the upper blade, two or more ngers o the let hand are inserted into the right posterolateral aspect o the hysterotomy. Te orceps handle is grasped by the right hand. Te blade toe is then gently introduced along the posterior let lower uterine segment wall. It is curved inward between the etal ace and the palmar surace o the ngers (Fig. 30-8A). Te ngers o the let hand are moved beneath the lower edge o this blade.

Upward pressure against this edge will sweep or wander the blade into position. As the blade reaches its nal position, the shank and handle come to rest in the midline, and the two handles are articulated (Fig. 30-8B). raction is up and out to guide the occiput through the hysterotomy. Concurrent, gentle undal pressure can be applied by an assistant.

Ater head delivery, a nger is passed across the etal neck to determine whether it is encircled by one or more umbilical cord loops. I present, these are slipped over the head. Te head is rotated to an occiput transverse position, which aligns the etal bisacromial diameter vertically. Te sides o the head are grasped with two hands, and gentle axial traction is applied until the anterior shoulder enters the hysterotomy incision. Next, by upward axial traction, the posterior shoulder is delivered. During delivery, abrupt or powerul lateral orce is avoided to avert brachial plexus injury. With steady outward traction, the rest o the body then readily ollows. Gentle undal pressure may aid this.

With some exceptions, current American Heart Association recommends against routine neonatal suctioning immediately ater birth, even with meconium present (Wycko, 2015). A uller discussion o this and delayed umbilical cord clamping is ound in Chapter 27 (p. 500). Specic to cesarean delivery, delayed clamping does not lower maternal hemoglobin levels on the rst postoperative day (Jenusaitis, 2020; Purisch, 2019).

FIGURE 30-9 Placenta bulging through the uterine incision as the uterus contracts. A hand gently massages the fundus to help aid spontaneous placental separation.

Ater the umbilical cord is clamped, the newborn is given to the team member who will conduct care. Comparing elective cesarean under neuraxial anesthesia and spontaneous vaginal deliveries, studies show that the need or neonatal resuscitation is not practically dierent between the two (Gordon, 2005). Te American Academy o Pediatrics and the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2017) recommend that “a qualied person who is skilled in neonatal resuscitation should be in the delivery room.” At Parkland Hospital, pediatric nurse practitioners attend uncomplicated, scheduled cesarean deliveries. Notably, as anticipated neonatal risks rise, so too should the resuscitative skills o the attendants (Wycko, 2015).

FIGURE 30-10 The cut edges of the uterine incision are approximated with a running, locking suture.o promote breasteeding, the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2020b) recommends skin-to-skin contact between newborn and mother in the delivery room. Although most randomized trials ocus on vaginal birth, several small studies support such contact ollowing cesarean delivery, and this is our practice (Frederick, 2020; Moore, 2016). Breast- eeding can be initiated the day o surgery.

Delivery of the Placenta. Te uterine incision is observed or any vigorously bleeding sites. Tese should be quickly clamped with Pennington or ring orceps. Although some surgeons may preer manual removal o the placenta, spontaneous delivery prompted by some gentle steady cord traction may reduce the risk o operative blood loss and inection (Anorlu, 2008; Baksu, 2005). raction is coupled with undal massage to hasten placental separation and delivery (Fig. 30-9). Immediately ater delivery and quick gross inspection o the placenta or missing portions, the uterine cavity is suctioned and wiped out with a gauze sponge to remove avulsed membranes, vernix, and clots. In the past, double-gloved ngers or ring orceps placed through the hysterotomy incision were used to dilate a closed cervix.

Tis does not reduce inection or postpartum hemorrhage rates and is not our practice (Kirscht, 2017; Liabsuetrakul, 2018). o help prevent uterine atony ater birth, an IV inusion containing two ampules or 20 units o oxytocin per liter o crystalloid is inused at 10 mL/min. Some preer higher inusion rates, however, nondilute boluses are avoided because o associated hypotension (Roach, 2013). Once the uterus contracts satisactorily, the rate can be reduced.

Although not available in the United States, an alternative is carbetocin, which is a longeracting oxytocin derivative. It provides suitable, albeit more expensive, hemorrhage prophylaxis (Kalaat, 2021). Other choices or hemorrhage prophylaxis include misoprostol (Cytotec) and the ergots, namely methylergonovine (Methergine) and ergonovine (Ergotrate). A combination agent o oxytocin plus ergonovine (Syntometrine) is used outside the United States. O agents, the World Health

Organization (2018) recommends oxytocin or rst-line use. Last, tranexamic acid (XA) can be added to a standard oxytocin inusion to help prevent blood loss. Despite early encouraging evidence, methodology aws have been cited (Franchini, 2018; Ker, 2016). With XA in one large trial, rates o estimated blood loss >1000 mL or red-cell transusion were lower than with placebo. But, XA did not lower rates o common blood loss–related secondary clinical outcomes (Sentilhes, 2021). In contrast to prevention, treatment o atony is ound in Chapter 42 (p. 734).

Uterine Repair. Ater placental delivery, the uterus is lited through the incision and onto the draped abdominal wall. We avor exteriorizing and believe a relaxed, atonic uterus can be recognized quickly and massage applied. Incision and bleeding points are more easily visualized and repaired, especially i extensions were torn or the patient is obese. Adnexal exposure is superior, and thus, tubal sterilization is easier. In contrast, some clinicians preer to close the hysterotomy with the uterus in situ. Comparing these two approaches, the Coronis Collaborative Group (2013) trial randomly assigned nearly 5000 parturients and ound no dierences in the endometritis or transusion rate. In one large metaanalysis, nausea and vomiting and associated pain rates were comparable with either method (Zaphiratos, 2015).

Beore hysterotomy closure, IUD insertion, i planned, is completed (Chap. 38, p. 668). Our practice is to perorm a primary needle and sponge count prior to uterine incision closure completion. For closure, one end o the uterine incision is grasped to stabilize and maneuver the incision. Te uterine incision is then closed with one or two layers o continuous 0- or no. 1 absorbable suture (Fig. 30-10). Chromic catgut suture is used by many, but some preer synthetic delayedabsorbable polyglactin 910 (Vicryl). In subsequent pregnancy, neither suture type is superior in mitigating against greater rates o adverse pregnancy outcomes such as uterine incision rupture (CORONIS Collaborative Group, 2016).

Single-layer closure is typically aster and is not associated with higher rates o inection or transusion (CAESAR Study Collaborative Group, 2010; Dodd, 2014; Roberge, 2014). Moreover, most studies observed that the number o layers does not signicantly aect complication rates in the next pregnancy (Chapman, 1997; CORONIS Collaborative Group, 2016; Durnwald, 2003). One randomized trial with nearly 1600 parturients ound a slightly greater ormation rate o cesarean scar niches at 3 months ater double-layer closure (Stegwee, 2021).

At Parkland Hospital, we use a one-layer uterine closure with chromic catgut. Te initial suture is placed just beyond one end o the uterine incision. A continuous, locking suture line or hemostasis is perormed, and each suture penetrates the ull myometrial thickness. Te suture line then extends to a point just beyond the incision’s opposite end. I bleeding sites or deects persist ater a single layer, more sutures are required.

Another layer o running suture or individually targeted gureeight or mattress stitches are options. Although not our routine practice, the peritoneum in the anterior cul-de-sac can be approximated with a continuous 2-0 chromic catgut suture line. Multiple randomized trials suggest that omission o this step causes no postoperative complications (Grundsell, 1998; Irion, 1996; Nagele, 1996). I tubal sterilization is planned, it is completed as described in Chapter 39 (p. 683).

Adhesions

Following cesarean delivery, adhesions commonly orm within the vesicouterine space or between the anterior abdominal wall and uterus. With each successive pregnancy, the percentage o aected women and adhesion severity rise (Morales, 2007; ulandi, 2009). Adhesions can signicantly lengthen incisionto-delivery time and total operative time (Rossouw, 2013; Sikirica, 2012). Rates o cystotomy and bowel injury also are raised because o adhesive disease (Rahman, 2009; Silver, 2006).

Intuitively, scarring can be reduced by handling tissues delicately, achieving hemostasis, and minimizing tissue ischemia, inection, and oreign-body reaction. Most recent data on shortand long-term outcomes show no benet to peritoneal closure (CAESAR Study Collaborative Group, 2010; CORONIS Collaborative Group, 2013, 2016; Kapustian, 2012). Similarly, most studies show no benet rom placement o an adhesion barrier at the hysterotomy site (Edwards, 2014; Kieer, 2016).

Abdominal Closure

Any laparotomy sponges are removed, and the paracolic gutters and cul-de-sac are gently suctioned o blood and amnionic uid. Some surgeons irrigate the gutters and cul-de-sac, especially in the presence o inection or meconium. Routine irrigation in low-risk women, however, leads to greater intraoperative nausea but not to lower postoperative inection rates (Eke, 2016; Viney, 2012).

Prior to abdominal closure, correct sponge and instrument counts are veried. Te rectus abdominis muscle bellies are allowed to all into place. Te overlying rectus ascia is closed by a continuous, nonlocking technique with a delayed-absorbable suture. In patients with a higher risk or inection, monolament suture may be preerable to braided material.

Te subcutaneous tissue usually need not be closed i it is <2 cm thick. With thicker layers, however, closure is recommended to minimize seroma and hematoma ormation, which can lead to wound inection, disruption, or both (Bohman, 1992; Chelmow, 2004). Adding a subcutaneous drain does not prevent signicant wound complications (Hellums, 2007; Ramsey, 2005).

Skin is closed with a running subcuticular stitch o 4-0 delayed-absorbable suture, with adhesive glue, or with staples. In comparison, nal cosmetic results and inection rates appear similar, skin suturing takes longer, but wound separation rates are higher with metal staples (Basha, 2010; Figueroa, 2013; Mackeen, 2014a, 2015). Poliglecaprone 25 (Monocryl) or polyglactin 910 (Vicryl) are both suitable (uuli, 2016). Outcomes with 2-octyl cyanoacrylate adhesive (Dermabond) were equivalent to sutures or Pannenstiel incisions (Daykan, 2017; Siddiqui, 2013). A sterile thin abdominal wound dressing is sufficient. In obese women, most evidence avors against a negative-pressure wound vacuum atop the closed skin incision compared with a standard wound dressing to lower wound inection rates (Gillespie, 2021; Hussamy, 2019; uuli, 2020). Joel-Cohen and Misgav Ladach Techniques

The Pfannenstiel-Kerr technique just described has been used for decades. Others include the more recent Joel-Cohen and Misgav Ladach techniques (Holmgren, 1999). These differ from traditional Pannenstiel-Kerr entry mainly by their initial incision placement and greater use o blunt dissection. Te Joel-Cohen technique creates a straight 10-cm transverse skin incision 3 cm below the level o the anterior superior iliac spines (Olosson, 2015). Te subcutaneous tissue layer is opened sharply 2 to 3 cm in the midline. Tis is carried down, without lateral extension, to the ascia. A small transverse incision is made in the ascia, and curved Mayo scissors are pushed laterally on each side and beneath intact subcutaneous at to incise the ascia. With this incision completed, an index nger rom each hand is inserted between the rectus abdominis muscle bellies and beneath the ascia. One nger is moved cranially and the other caudally, in opposition, to separate the bellies and urther open the ascial incision. Ten, a nger rom each hand hooks under each belly to stretch the muscles laterally.

Te peritoneum is entered sharply, and this incision is sharply extended cephalocaudad. Entry with the Misgav Ladach technique diers in that the peritoneum is entered bluntly (Holmgren, 1999). Modications to the Joel-Cohen method abound. For emergency delivery, we begin along a line somewhat lower on the abdomen and similar to that or Pannenstiel incision. For speed, we extend the initial ascial incision bluntly by hooking index ngers in the ascial incision’s lateral corners and pulling laterally (Homeyr, 2009; Oloson, 2015). Index ngers insinuated between the rectus bellies then move cephalocaudad in opposition to separate the muscle bellies. Blunt index-nger dissection enters the peritoneum, and again, cranial and caudad opposing stretch lengthens the peritoneal incision. Last, all the layers o the abdominal wall are grasped together and pulled laterally in opposition to urther open the operating space.

Tese techniques have been associated with shorter operative times and with lower rates o intraoperative blood loss and postoperative pain (Mathai, 2013). They may, however, prove difficult or women with preexisting anterior rectus brosis and peritoneal adhesions (Bolze, 2013).

FIGURE 30-11 An initial small vertical hysterotomy incision is made in the lower uterine segment. Fingers are insinuated between the myometrium and fetus to avoid fetal laceration. Scissors extend the incision cephalad as needed for delivery. (Figures 30-11 and 30-12: Reproduced with permission from Johnson DD: Cesarean delivery. In Yeomans ER, Hoffman BL, Gilstrap LC III, et al (eds): Cunningham and Gilstrap’s Operative Obstetrics, 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2017.)Classical Cesarean Incision

Indications. Tis incision is usually avoided because it encompasses the active upper uterine segment and thus is prone to rupture with subsequent pregnancies. Some indications stem rom difculty in exposing or saely entering the lower uterine segment. For example, a densely adhered bladder rom previous surgery is encountered; a leiomyoma occupies the lower uterine segment; or the cervix is currently invaded by cancer.

Women with prior radical trachelectomy or cervix cancer are usually delivered by classical incision. Massive maternal obesity can preclude sae access to the lower uterine segment. A classical incision is also preerred or placenta previa with anterior implantation, especially those complicated by placenta accreta syndrome. In extreme cases o this, the typical classical hysterotomy may be placed even higher in the uterine body or posteriorly to avoid the placenta. Fetuses with cephalic presentation are then delivered in a manner similar to total breech extraction.

In other instances, etal indications dictate the need. Transverse lie of a large fetus, especially i the membranes are ruptured and the shoulder is impacted in the birth canal, usually requires a classical incision. Second, with a etus presenting as a back-down transverse lie, the back precludes easy grasping o a leg through a transverse uterine incision or breech delivery. Here, a classical incision provides superior room. Tird, in instances when the etus is very small and breech, a classical incision may be preerable (Osmundson, 2013). In such cases, the poorly developed lower uterine segment provides inadequate space or the manipulations required or breech delivery. Or, less commonly, the small etal head may become entrapped by a contracting uterine undus ollowing membrane rupture. With multiple etuses, a classical incision again may provide needed room or extraction o etuses that may be malpositioned or preterm (Osmundson, 2015). A large etal malormation or conjoined twins may require the added space aorded by a classical incision.

Uterine Incision and Repair. A vertical uterine incision is initiated with a scalpel beginning as low as possible and preerably within the lower uterine segment (Fig. 30-11). I adhesions, insufcient exposure, a tumor, or placenta percreta preclude development o a bladder ap, then the incision is made above the level o the bladder. Described earlier (p. 553), back lling the bladder may aid this.

Once the uterus is entered with a scalpel, the incision is extended cephalad with bandage scissors until it is long enough to permit etal delivery. With scissor use, the etus can be better protected rom laceration. Fingers o the surgeon’s nondominant hand are insinuated between the myometrium and etus to prevent scissor cuts. As the incision is opened, numerous large vessels that bleed prousely are commonly encountered within the myometrium. Te remainder o etal and placental delivery mirrors that with a low transverse hysterotomy.

FIGURE 30-12 Classical incision closure. The deeper half (A) and superficial half (B) of the incision are closed in a running fashion. The serosa is then closed (C).

For incision closure, one method employs a layer o 0- or no. 1 chromic catgut with a running stitch to approximate the deeper length o the incision (Fig. 30-12). Te outer layer o myometrium is then closed along its length with similar suture and with a running suture line. o achieve good approximation and to prevent the suture rom tearing through the myometrium, it is helpul to have an assistant relieve tension by compressing the uterus on each side o the wound toward the midline as each stitch is placed.

PERIPARTUM HYSTERECTOMY

■ Indications

Hysterectomy is most commonly perormed to arrest or prevent hemorrhage rom intractable uterine atony, surgical trauma/tears, or abnormal placentation (Bateman, 2012; Kallianidis, 2020). It is more oten completed during or ater cesarean delivery but may be needed ollowing vaginal birth. Among all deliveries, the peripartum hysterectomy rate in the United States approximates 1 per 1000 births and has risen signicantly during the past ew decades (Bateman, 2012; Govindappagari, 2016). During a 25-year period, the rate o peripartum hysterectomy at Parkland Hospital was 1.7 per 1000 births (Hernandez, 2012). Most o this rise is attributed to the increasing rates o cesarean delivery and its associated complications in subsequent pregnancy (Flood, 2009; Orbach, 2011). O hysterectomies, approximately one hal to two thirds are total, whereas the remaining cases are supracervical (Rossi, 2010; Shellhaas, 2009).

FIGURE 30-13 The round ligaments are clamped, ligated, and transected bilaterally. (Figures 30-13 to 30-21: Reproduced with permission from Cunningham FG, Gilstrap LC III: Peripartum hysterectomy. In Yeomans ER, Hoffman BL, Gilstrap LC III, et al (eds): Cunningham and Gilstrap’s Operative Obstetrics, 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2017.)

FIGURE 30-14 The posterior leaf of the broad ligament adjacent to the uterus is perforated just beneath the fallopian tube, uteroovarian ligaments, and ovarian vessels.

FIGURE 30-15 The uteroovarian ligament and fallopian tube are clamped and cut. The lateral pedicle is doubly ligated.

FIGURE 30-16 The posterior leaf of the broad ligament is divided inferiorly toward the uterosacral ligament.

FIGURE 30-17 The bladder is dissected sharply from the lower uterine segment.

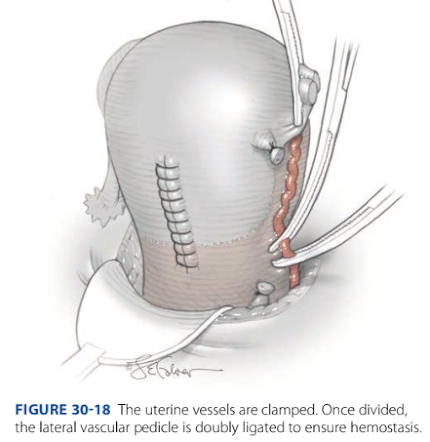

FIGURE 30-18 The uterine vessels are clamped. Once divided, the lateral vascular pedicle is doubly ligated to ensure hemostasis.

FIGURE 30-19 The cardinal ligaments are clamped, incised, and ligated.

FIGURE 30-20 A curved clamp is placed across the lateral vaginal fornix below the level of the cervix, and the tissue incised medially to the point of the clamp.

Major complications o peripartum hysterectomy include greater blood loss and risk o urinary tract damage. Blood loss is usually appreciable because hysterectomy is being perormed or hemorrhage that requently is torrential, and the procedure itsel is associated with substantial bleeding. Although many cases with hemorrhage cannot be anticipated, those with abnormal implantation are oten identied antepartum. Preparations or placenta accreta syndrome are discussed in Chapter 43 (p. 763) and are outlined by the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2018). An important actor aecting the cesarean hysterectomy complication rate is whether the operation is perormed electively or emergently. With anticipated or planned cesarean hysterectomy, rates o blood loss, blood transusion, and urinary tract complications are lower those with emergent procedures (Briery, 2007; Glaze, 2008).

■ Hysterectomy Technique

otal or supracervical hysterectomy is perormed using standard operative techniques. Adequate exposure is essential, but initially, placement o a sel-retaining retractor such as a Bal- our is not necessary. Rather, satisactory exposure is obtained with cephalad traction on the uterus by an assistant, along with handheld Richardson or Deaver retractors. Te bladder ap is deected caudad to the level o the cervix i possible to permit total hysterectomy. In cases in which cesarean hysterectomy is planned or strongly suspected, extended bladder ap dissection is ideally completed beore initial hysterotomy. Later attempts at bladder dissection may be obscured by bleeding, or excess blood may be lost during this dissection.

Ater cesarean delivery, the placenta is typically removed. In cases o placenta accreta syndrome or which hysterectomy is already planned, the placenta is usually let undisturbed in situ. I the hysterotomy incision is bleeding appreciably, it can be quickly reapproximated with ull-thickness sutures, or Pennington or sponge orceps can be applied or hemostasis. I bleeding is minimal, neither maneuver is necessary.

Te round ligament is divided close to the uterus between clamps, and each pedicle is ligated (Fig. 30-13). Either 0 or no. 1 suture can be used in either chromic gut or delayed-absorbable material. Division o the round provides access to the anterior lea o the broad ligament, which is incised downward to meet the ormer bladder ap incision. Te posterior lea o the broad ligament adjacent to the uterus is bluntly or sharply perorated at a point beneath the allopian tube, uteroovarian ligament, and ovarian vessels (Fig. 30-14). Tese structures together are then divided between sturdy clamps placed close to the uterus (Fig. 30-15). Te lateral pedicle is doubly ligated.

Te medial clamp remains and is removed later with the entire uterine specimen. Te posterior lea o the broad ligament is then incised caudad toward the uterosacral ligaments (Fig. 30-16). Te bladder and attached peritoneal ap are urther deected and dissected as needed. I the bladder ap is densely adhered, as it may be ater previous hysterotomy incisions, careul sharp dissection is employed (Fig. 30-17).

Special care is required rom this point on to avoid injury to the ureters, which pass beneath the uterine arteries. o help accomplish this, an assistant places constant traction to pull the uterus in the direction away rom the side on which the uterine vessels are being ligated. Te ascending uterine artery and veins on either side are identied. Tese vessels are then clamped adjacent to the uterus (Fig. 30-18). For security, some may preer two lateral clamps. Te medial-most clamp helps prevent back bleeding rom the uterus. Te uterine vessels are divided, and the lateral tissue pedicle is doubly suture ligated. Te medial clamp remains or later removal with the specimen. Ater securing the uterine vessels on one side, the round ligament, adnexal pedicle, and uterine vessels are then addressed on the contralateral side.

In cases with prouse hemorrhage, time and rapid hemostasis can be gained by quickly clamping and dividing all o the just-described pedicles. Once all are clamped, the surgical team can then return to ligate each pedicle individually.

Total Hysterectomy

Even i total hysterectomy is planned, we nd it technically easier in many cases to nish the operation ater amputating the uterine undus and placing Ochsner or Kocher clamps on the cervical stump or traction and hemostasis. Sel-retaining retractors also may be placed at this time. o remove the cervix, the bladder is mobilized urther i needed. Tis carries the ureters caudad as the bladder is retracted beneath the symphysis.

Bladder retraction can also help prevent laceration or suturing o the bladder during cervical excision and vaginal cu closure. Te cardinal ligament, the uterosacral ligaments, and the many large vessels within these ligaments are clamped systematically with sturdy Heaney-type curved or straight clamps (Fig. 30-19). Te clamps are placed as close to the cervix as possible, taking care not to include excessive tissue in each clamp. Te tissue between the pair o clamps is incised, and the lateral pedicle is suture ligated. Tese steps are repeated caudally and bilaterally until the level o the lateral vaginal ornix is reached on each side. In this way, the descending branches o the uterine vessels are clamped, cut, and ligated as the cervix is separated rom the cardinal ligaments.

FIGURE 30-21 A transfixing stitch is placed on each side to close the lateral vaginal cuff. Interrupted stitches (dotted lines) may be needed to close any midline gap.

I the cervix is eaced and dilated considerably, its sotness may obscure palpable identication o the cervicovaginal junction. Te junction location can be ascertained either through the open hysterotomy incision or through a vertical uterine incision made anteriorly in the midline at the level o the ligated uterine vessels. A nger is directed ineriorly through the incision to identiy the ree margin o the dilated, eaced cervix.

FIGURE 30-22 Cystotomy repair. A. The primary layer inverts the bladder mucosa with running or interrupted sutures of 3-0 delayed-absorbable or absorbable suture. B. Second and possibly a third layer approximate the bladder muscularis to reinforce the incision closure. (Reproduced with permission from Balgobin S: Urologic and gastrointestinal injuries. In Yeomans ER, Hoffman BL, Gilstrap LC III, et al (eds): Cunningham and Gilstrap’s Operative Obstetrics, 3rd ed. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2017.)

Te contaminated glove is replaced. Another useul method to identiy the cervical margins in cases o planned hysterectomy is to transvaginally place our metal skin clips or brightly colored sutures at 12, 3, 6, and 9 o’clock positions on the cervical edges. Immediately below the level o the cervix, a curved clamp is placed across the lateral vaginal ornix on each side, and the vagina is incised above the clamp (Fig. 30-20). Te cervix is inspected to ensure that it has been completely removed. A transxing suture is used or vaginal cu closure as each clamp is removed. Interrupted stitches may be added to approximate the middle portion o the cu (Fig. 30-21). Each lateral vaginal ornix is secured to the uterosacral ligaments to mitigate later vaginal prolapse. For cu closure, some surgeons instead preer to close the vagina by apposing the anterior and posterior vaginal walls with interrupted gure-eight sutures or running suture line

All sites are examined careully or bleeding. One technique is to perorm a systematic bilateral survey rom the allopian tube and ovarian ligament pedicles to the vaginal vault and bladder ap. Bleeding sites are ligated with care to avoid the ureters. Te abdominal wall normally is closed in layers, as previously described or cesarean delivery (p. 558).

Supracervical Hysterectomy

o perorm a subtotal hysterectomy, the uterine body is amputated immediately above the level o uterine artery ligation. Te cervical stump may be closed with a continuous or interrupted suture line o chromic catgut or delayed-absorbable material. Subtotal hysterectomy is oten all that is necessary to stop hemorrhage. It may be preerred or women who would benet rom a shorter surgery or or those with extensive adhesions that threaten signicant urinary tract injury.

Salpingo-oophorectomy

Because o the large adnexal vessels and their close proximity to the uterus, it may be necessary to remove one or both adnexa to obtain hemostasis. Briery and colleagues (2007) reported unilateral or bilateral oophorectomy in a ourth o cases. Preoperative counseling or anticipated hysterectomy should include this possibility.

■ Urinary Tract or Bowel Injury

Tese injuries are rare during cesarean delivery. Te bladder laceration rate approximates 2 injuries per 1000 cesarean deliveries, whereas that or ureteral trauma nears 0.3 events per 1000 cases (Güngördük, 2010; Oliphant, 2014). Bowel is damaged in about 1 in 1000 cesarean deliveries (Silver, 2006).

Cystotomy

Bladder laceration most commonly occurs during blunt or sharp dissection in the vesicouterine space to create the bladder ap, during peritoneal cavity entry, and during hysterotomy (Phipps, 2005; Rahman, 2009). Risks are prior cesarean delivery; comorbid adhesive disease; emergency cesarean delivery; cesarean hysterectomy, especially cases with morbidly adherent placenta; and surgery in second-stage labor compared with rst-stage (Alexander, 2007; Salman, 2017; Silver, 2006).

Bladder injury is typically identied intraoperatively, and a clear-uid gush or the Foley bulb are indicators. In suspected cases, cystotomy can be conrmed with retrograde instillation o uid through a Foley catheter and into the bladder. Dilute sterile inant ormula is a common, available option. Methylene blue–stained saline is another. Leakage o the indicator uid aids laceration identication and delineation o its borders. Te dome is lacerated most oten, and trigone injuries make up the remainder (Phipps, 2005; Salman, 2017).

Prior to cystotomy repair, ureters are examined, and urine jets rom each orice are sought. Inspection can be done directly through the cystotomy, i at the dome. A separate diagnostic extraperitoneal cystotomy may be preerable i the laceration nears the trigone. o aid viewing, urine jets can be colored by IV dye, as described in the next section.

Once ureteral patency is conrmed, the bladder can be closed with a two- or three-layer running closure using a 3-0 absorbable or delayed-absorbable suture (Fig. 30-22). Te rst layer inverts the mucosa into the bladder. Subsequent layers reapproximate the bladder muscularis. Ater the nal layer, the bladder is lled with a marker uid to demonstrate repair integrity. Leaking deects are closed with interrupted reinorcing stitches.

Postoperative care requires continuous bladder drainage or 7 to 14 days to permit healing and minimize the risk o stula ormation. Uropathogen prophylaxis during this drainage is not required. Prior to catheter removal, cystourethrography may not be needed or a simple, single laceration measuring under 1 cm (Glaser, 2019).

Larger lacerations in or near the trigone require careul attention. Specialists may be consulted, and in preparation, ureteral catheters, described in the next section, can be assembled. Ureteral orices are directly inspected to document jets rom both. I not seen, a ureteral catheter may be passed through the cystotomy and into each orice to conrm patency. Once this is conrmed, repair should not disrupt the ureteral orices, and stents may remain to ensure their patency.

Unrecognized cystotomy can maniest postoperatively as hematuria, oliguria, abdominal pain, ileus, ascites, peritonitis, ever, urinoma, or stula. For diagnosis, retrograde cystography or abdominal computed tomography (C) with cystography can be used (arney, 2013). Cystoscopy is also an option but may require a procedural room. Once cystotomy is identied, prompt repair is indicated (Balgobin, 2017).

Ureteral Injury

Te ureter may be at risk during cesarean hysterectomy, especially those complicated by placenta accreta syndrome. (Woldu, 2014). Although not our practice, some advocate preoperative ureteral catheter placement to aid intraoperative ureter identication (Eller, 2009; Matsubara, 2013).

Organization guidelines recommend individualization o this practice depending on anticipated placenta accreta syndrome complexity (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2018; Collins, 2019). Further, initial dorsal lithotomy positioning o the patient or these cases can permit cystoscopy. Aside rom hysterectomy, the ureter is also at risk during repair o hysterotomy extensions into the broad ligament or vagina (Sa- rai, 2020).

I ureteral injury is suspected, IV dye is administered, and the pelvis is directly inspected or extravasation. O options, 50 mg o IV methylene blue may be given over 5 minutes. However, methylene blue carries the potential or inciting methemoglobinemia in patients with glucose- 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deciency. Another option is 25 or 50 mg o IV 10-percent sodium uorescein, which stains bright yellow (EspaillatRijo, 2016; Grimes, 2017).

Next, brisk dye-stained urine jets are sought rom each ori- ce to exclude ureteral kinking or ligation. Orice viewing may be via cystoscopy, i available; through a comorbid traumatic cystotomy; or through an intentional diagnostic cystotomy. For the last, a midline extraperitoneal cystotomy in the bladder dome gives excellent exposure. Sluggish or absent jets may reect patient hypovolemia, and ongoing volume resuscitation may yield expected orice jets. I not, consultation with a specialist is typically requested to exclude ureteral injury.

While waiting, catheters and stents can be assembled. Semantically, ureteral catheters are diagnostic tools, and typically are inserted and removed in the same therapeutic intervention. Most stents are designed to remain indwelling or prolonged ureteral drainage. Both types are hollow to permit radiopaque medium injection and to allow urine egress through or around them (Corton, 2020). o exclude ureteral obstruction, a 4F to 6F open-ended or whistle-tip catheter is threaded into one orice. Once inserted, the catheter is advanced to the level o suspected obstruction. I the tool threads easily up toward the renal pelvis, obstruction is unlikely. In most, ureteral injury occurs at or below the pelvic brim, and the distance rom the ureteral orice to the brim approximates 13 cm (Jackson, 2019). Failure to easily advance the catheter may indicate ureteral kinking, ligation, or crush injury. Te appearance o the catheter in the abdominal cavity indicates partial or complete transection (Balgobin, 2017)

Repair o ureteral injuries is dependent upon the type o injury and location.

First, kinked or ligated ureters can be relieved by release o ensnaring sutures. Crush injuries are inspected to ensure vital tissue. In these cases, stents are let to avert ureteral stricture. Ureteral stents range rom 4F to 7F. Stents vary in length rom 20 to 30 cm, and a 24-cm or 26-cm length is appropriate or most adults. Double-pigtail or double-J stents describe their tip shape, and the ends coil within the renal pelvis and bladder, respectively, to prevent stent migration (Corton, 2020). A Foley catheter remains or 7 to 10 days, and the ureteral stents are removed via cystoscopy ater 14 days. Intravenous pyelography (IVP) is usually not necessary beore removal o the stent i it was placed as a precautionary measure ater relatively minor injury (Davis, 1999). Crush injuries with devascularization, thermal injury, or transection require more extensive repair. I a healthy-appearing ureter can be reimplanted into the bladder without undue tension, then ureteroneocystostomy is preerable. For more proximal injuries, a ureteroureterostomy, a psoas hitch, or a Boari ap may be needed. An explanation o these more extensive procedures is ound in Cunningham and Gilstrap’s Operative Obstetrics, 3rd edition (Balgobin, 2017).

Unrecognized ureteral injury can mimic that o cystotomy with the addition o possible costovertebral angle tenderness. C urography is a preerred initial diagnostic tool (Sharp, 2016). Te duration o time rom injury to identication directs repair. Tose identied early are oten suitable or immediate repair.

Bowel Injury

Serosal tears represent weak points in the small bowel. I obstruction develops postoperatively, these weak spots may perorate, leading to peritonitis. I serosal tears are ew, they can be oversewn with either a ne absorbable or nonabsorbable suture (Davis, 1999). More signicant lacerations are oten repaired in consultation with a general surgeon or gynecologic oncologist.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

■ Euvolemia Evaluation

During and ater cesarean delivery, requirements or IV uids can vary considerably. Current ERAS strategies aim or euvolemic replacement (Caughey, 2018). Administered uids consist o either lactated Ringer solution or a similar crystalloid solution with 5-percent dextrose. Blood loss with uncomplicated cesarean delivery approximates 1000 mL. Te averagesized woman with a hematocrit o 30 percent or more and with a normally expanded blood and extracellular uid volume most oten will tolerate blood loss up to 2000 mL without difculty.

Unappreciated bleeding through the vagina during the procedure, bleeding concealed in the uterus ater its closure, or both commonly lead to underestimation. Blood loss averages 1500 mL with elective cesarean hysterectomy, although this is variable (Pritchard, 1965). Most peripartum hysterectomies are unscheduled, and blood loss in these cases is correspondingly greater. Tus, in addition to close monitoring o vital signs and urine output, the hematocrit should be determined intra- or postoperatively as indicated.

■ Recovery Suite

Te amount o vaginal bleeding is closely monitored or at least an hour in the immediate postoperative period. Te uterine undus is also identied requently by palpation to ensure that the uterus remains rmly contracted. Criteria or transer to the postpartum ward include minimal bleeding, stable vital signs, and adequate urine output.

■ Hospital Care until Discharge

Analgesia, Vital Signs, Intravenous Fluids

Several schemes are suitable or postoperative pain control. First, adding intrathecal opioid or epidural opioid such as morphine to neuraxial analgesia can provide 12 to 24 hours o postoperative relie (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2019a; Caughey, 2018). Sedation and respiratory depression rise with increasing intrathecal opioid doses. Postoperative monitoring protocols reect this and are outlined in Chapter 25 (p. 472) (Bauchat, 2019). Other potential side eects include pruritus, nausea, or vomiting (Sultan, 2016). Despite these, long-acting neuraxial analgesia is recommended instead o intermittent parental opioid dosing (American Society o Anesthesiologists, 2016). For additional relie, nonsteroidal antiinammatory drugs (NSAIDs) can alternate with acetaminophen (Ong, 2010). Breakthrough pain can be relieved by oxycodone 2.5 to 5 mg every 4 hours (Bollag, 2021). Neonatal sedation is a concern, and total oxycodone doses higher 30 mg/d are not recommended (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2019a). Instead, or severe breakthrough pain, intramuscular (IM) meperidine, 50 to 75 mg every 3 to 4 hours, or IM morphine, 10 to 15 mg every 3 to 4 hours, is an option.

For those without neuraxial anesthesia, a transversus abdominis place (AP) block can be considered (Fig. 2-2, p. 14). Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) also is reasonable. One PCA regimen uses IV morphine given as needed as a 1-mg dose with a 6-minute lockout interval and maximum dose o 30 mg in 4 hours. An additional 2-mg booster dose is permitted or a maximum o two doses. Ater transer to her room, the woman is assessed at least hourly or 4 hours, and thereater at intervals o 4 hours. Deep breathing and coughing are encouraged to prevent atelectasis.

Vital signs, uterine tone, urine output, and vaginal and incisional bleeding are evaluated. Te hematocrit is routinely measured the morning ater surgery. It is checked sooner i blood loss was signicant or i postoperative hypotension, tachycardia, oliguria, or other evidence suggests hypovolemia. I the hematocrit is signicantly lower than the preoperative level, the measurement is repeated and a search or the cause is instituted. Clinical and objective thresholds or transusion are described ully in Chapter 44 (p. 771). I ongoing blood loss is not expected, iron therapy is preerred to transusion.

Postpartum, the patient begins to mobilize and excrete her physiologically expanded extravascular volume. Tus, maintenance IV uid proves adequate ater surgery until consistent oral intake is reestablished. I urine output alls below 30 mL/hr, however, a woman should be reevaluated promptly.

Te cause o the oliguria may range rom unrecognized blood loss to an antidiuretic eect rom inused oxytocin. Women undergoing unscheduled cesarean delivery may have pathological retention or constriction o the extracellular uid compartment caused by severe preeclampsia, sepsis syndrome, vomiting, prolonged labor without adequate uid intake, or increased blood loss. Women with these complications are generally observed in the recovery room until improved.

Bladder and Bowel Function

A Foley catheter is oten required to accurately assess urinary output. For women not needing such monitoring, organizations dier in their recommendations. Te Society or Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology suggests removal ater 6 to 12 hours and cites the urinary retention risks associated with long-acting neuraxial anesthesia (Bollag, 2021). Te ERAS Society recommends immediate postoperative removal (Macones, 2019). Te prevalence o urinary retention ollowing cesarean delivery approximates 5 percent (Chap. 36, p. 643). Failure to progress in labor and postoperative narcotic analgesia are identied risks (Chai, 2008; Liang, 2007).