Chapter 36. The puerperium

BS. Nguyễn Hồng Anh

The word puerperium is derived from Latin—puer, child + parus, bringing forth. It defines the time following delivery during which pregnancy-induced maternal anatomical and physiological changes return to the nonpregnant state. Its duration is inexact but is considered to last between 4 and 6 weeks. Although much less complex compared with pregnancy, the puerperium has appreciable changes, and maternal morbidity is surprisingly common. For example, in a survey of 1246 British mothers, 3 percent required hospital readmission within 8 weeks (Tompson, 2002). Moreover, almost three fourths of women continue to have health problems for up to 18 months (Glazener, 1995).

Of self-reported concerns, pain, breastfeeding, and psychosocial topics are prominent. Table 36-1 lists data on these from the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Surveillance System—PRAMS—of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

THE FOURTH TRIMESTER

Because the weeks following childbirth are a critical period for the woman and her infant, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2018a) promulgated the concept of a “fourth trimester.” This concept reinforces the importance of the 12 weeks following birth, and components of this model

are outlined in Table 36-2. Thus, the comprehensive postpartum visit includes a full assessment of physical, social, and psychological well-being.

An initial visit is recommended at 3 weeks postdelivery and a nal summary visit at 12 weeks. Between this time, visits can be added as needed. For example, women with chronic hypertension, overt diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and depression may require additional multidisciplinary care during this period. For all puerpera, a discussion o positive liestyle changes can be initiated. Tis time also aords the opportunity to update immunizations (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2019). At the end o the 12-week ourth

trimester, ollow-up then transitions into well-woman care, ongoing primary or specialty care, and when necessary, preconceptional counseling (Chap. 9, p. 165).

REPRODUCTIVE TRACT INVOLUTION

■ Birth Canal

Return of the tissues in the birth canal to the nonpregnant state begins soon after delivery. The vagina and its outlet gradually diminish in size but rarely regain their nulliparous dimensions. Rugae begin to reappear by the third week but are less prominent than before. The hymen is represented by several small tags of tissue, which scar to form the myrtiform caruncles. The vaginal epithelium reflects the hypoestrogenic state, and it does not begin to proliferate until 4 to 6 weeks. This timing is usually coincidental with resumed ovarian estrogen production.

Lacerations or stretching of the perineum during delivery can lead to vaginal outlet relaxation. Some damage to the pelvic floor may be inevitable, and parturition predisposes to pelvic organ prolapse (Chap. 30, p. 548).

■ Uterus

The massively augmented uterine blood flow necessary to maintain pregnancy derives from signicant hypertrophy and remodeling of pelvic vessels. After delivery, their caliber gradually diminishes to approximately that of the prepregnant state.

Within the puerperal uterus, larger blood vessels become obliterated by hyaline changes. They are gradually resorbed and replaced by smaller ones. Minor vestiges of the larger vessels, however, may persist for years.

During labor and vaginal delivery, the margin of the dilated cervix, which corresponds to the external os, may be lacerated. The cervical opening contracts slowly, and for a few days immediately after labor, it readily admits two fingers. By the end of the first week, this opening narrows, the cervix thickens, and the endocervical canal reforms. The external os does not completely resume its pregravid appearance. It remains somewhat wider, and typically, ectocervical depressions at the site of lacerations become permanent. These changes are characteristic of a parous cervix (Fig. 36-1). Cervical epithelium also undergoes

considerable remodeling. This actually may be salutary because almost half of women have regression of high-grade dysplasia ollowing delivery (Ahdoot, 1998; Kaneshiro, 2005).

Ater delivery, the undus o the contracted uterus lies slightly below the umbilicus. It consists mostly o myometrium covered by serosa and internally lined by decidua. Te markedly attenuated lower uterine segment contracts and retracts, but not as orceully as the uterine corpus. During the next ew weeks, the lower segment is converted rom a clearly distinct substructure large enough to accommodate the etal head to a barely discernible uterine isthmus located between the corpus and internal cervical os. Immediately postpartum, the anterior and posterior walls, which lie in close apposition, are each 4 to 5 cm thick (Buhimschi, 2003). At this time, the uterus weighs approximately 1000 g.

Myometrial involution is a truly remarkable eat o destruction or deconstruction that begins as soon as 2 days ater delivery (Williams, 1931). Te total number o myocytes does not decline appreciabl —rather, their size decreases markedly. Weights rom removed uteri approximate 500 g by 1 week postpartum, 300 g by 2 weeks, and at 4 weeks, involution is complete and the uterus weighs approximately 100 g ( Williams, 1931). Ater each successive delivery, the uterus is usually slightly larger than beore the most recent pregnancy.

Sgraph Fdgs

Uterine involution and declining uterine volume is best measured by sonography (Fig. 36-2) (Wataganara, 2015). With this, estimates again show uterine size declines o more than hal, rom 450 to 200 g, in the rst 2 weeks. Sonographically, the uterus and endometrium return to the pregravid size by 8 weeks postpartum. Complete involution in the multiparous uterus is longer than or the nulliparous organ (Paliulyte, 2017). In the event o a cesarean delivery, the residual myometrial thickness over the uterine incision is thicker i a two-layer closure was used (Roberge, 2016).

In a study o 42 normal puerperas, uid in the endometrial cavity was noted in 78 percent o women at 2 weeks, 52 percent at 3 weeks, 30 percent at 4 weeks, and 10 percent at 5 weeks (ekay, 1993). Belachew and coworkers (2012) used three-dimensional sonography and visualized intracavitary tissue matter in a third on day 1, 95 percent on day 7, 87 percent on day 14, and 28 percent on day 28. By day 56, the small cavity was empty.

Doppler ultrasound o the uterine artery shows continuously increasing vascular resistance throughout the rst 7 weeks postpartum (Sohn, 1988; Wataganara, 2015). Uterine artery ow impedance does not dier between women undergoing vaginal versus cesarean delivery (Baron, 2016).

Ddual ad edmral Rgra

Because separation of the placenta and membranes involves the spongy layer, the decidua basalis is not sloughed. Te in situ decidua varies markedly in thickness, it has an irregular jagged border, and it is inltrated with blood, especially at the placental site. Within 2 or 3 days after delivery, the remaining decidua becomes dierentiated into two layers. Te supercial layer becomes necrotic and is sloughed in the lochia. Te basal layer adjacent to the myometrium remains intact and is the source o new endometrium. Decidual vessels are near normal by delivery and endovascular trophoblasts are diminished. Tese vessels and the spiral arteries also undergo involution (Zhang, 2018).

Endometrial regeneration is rapid, except at the placental site. Within a week or so, the ree surace becomes covered by epithelium. Sharman (1953) identied a ully restored endometrium in all biopsy specimens obtained rom the 16th day onward. Histological endometritis is part o the normal reparative process. Also, microscopic inammatory changes characteristic o noninectious acute salpingitis are seen in almost hal o women between 5 and 15 days (Andrews, 1951).

Afrpas. Several clinical ndings coincide with uterine involution. In primiparas, the uterus tends to remain tonically contracted ollowing delivery. In multiparas, however, it oten contracts vigorously at intervals and gives rise to afterpains, which are similar to but milder than labor contractions. Tese are more pronounced as parity increases and worsen when the newborn suckles, likely because o oxytocin release (Holdcrot, 2003). Usually, aterpains decrease in intensity and become mild by the third day. We have encountered unusually severe and persistent aterpains in women with postpartum uterine inections (Chap. 37, p. 651).

Lha. Early in the puerperium, sloughing o decidual tissue

results in a vaginal discharge o variable quantity. Te discharge

is termed lochia and contains erythrocytes, shredded decidua,

epithelial cells, and bacteria. For the rst ew days ater delivery,

there is blood sufcient to color it red—lochia rubra. Ater 3

or 4 days, lochia becomes progressively pale in color—lochia

serosa. Ater approximately the 10th day, because o an admixture o leukocytes and reduced uid content, lochia assumes a

white or yellow-white color—lochia alba. Te average duration

o lochial discharge ranges rom 24 to 36 days (Fletcher, 2012).

Because o this expected leukocyte component, saline preparations o lochia or microscopic evaluation in cases o suspected

puerperal metritis are typically uninormative.

PLACENTAL SITE INVOLUTION

Complete extrusion of the placental site takes up to 6 weeks (Williams, 1931). Immediately after delivery, the placental site is approximately palm-sized. Within hours of delivery, it normally contains many thrombosed vessels that ultimately undergo organization. By the end of the second week, it measures 3 to 4 cm in diameter.

Placental site involution is an exfoliation process, which is prompted in great part by undermining of the implantation site by new endometrial proliferation (Williams, 1931). Thus, involution is not simply absorption in situ. Exfoliation consists of both extension and “downgrowth” of endometrium from the margins of the placental site, as well as “upward” development of endometrial tissue from the glands and stroma left deep in the decidua basalis after placental separation. Anderson and Davis (1968) concluded that placental site exfoliation results from sloughing of infarcted and necrotic superficial tissues followed by a remodeling process.

■ Subinvolution

In some cases, uterine involution is hindered because of incompletely remodeled spiral arteries, retained placental fragments, or infection. Such subinvolution is accompanied by varied intervals of prolonged lochia and by irregular or excessive uterine bleeding. During bimanual examination, the uterus is larger and softer than would be expected.

Inadequate conversion of spiral arteries into remodeled uteroplacental arteries can cause subinvolution (Kavalar, 2012). These noninvoluted vessels are filled with thromboses and lack an endothelial lining. Perivascular trophoblasts are also identi- fied in the vessel walls, which suggests an aberrant interaction

between uterine and trophoblast cells.

With bleeding, pelvic sonography may help differentiate subinvolution from retained placenta. Characteristic findings of retained products include a thickened endometrium or endometrial mass (Fig. 36-3). Vascularity within this area increases the likelihood of retained products (Sellmyer, 2013). Comparatively, subinvolution is characterized by an enlarged uterus with tubular hypoechoic areas in the myometrium. These tubular structures reect neovascularization and dilated uterine vessels. For treatment, uterotonics are recommended by many but their efcacy is questionable (Hoyveda, 2001; American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017d). At Parkland hospital, conservative management is undertaken with methylergonovine (Methergine) 0.2 mg orally every 3 to 4 hours or 24 to 48 hours. For initially brisk bleeding, an intramuscular dose o methylergonovine may be coupled with an inusion o synthetic oxytocin (Pitocin) (20 units in 1 L crystalloid).

For cases with suspected comorbid inection, antimicrobial therapy usually leads to a good response. Wager and associates (1980) reported that a third of late cases o postpartum metritis are caused by Chlamydia trachomatis. Empirical therapy with azithromycin or doxycycline usually prompts resolution

regardless o bacterial etiology. At our institution, common oral options taken twice daily or 7 to 10 days include azithromycin, 500 mg; amoxicillin-clavulanate (Augmentin), 875 mg; or doxycycline, 100 mg.

■ Late Postpartum Hemorrhage

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2017d) defines secondary postpartum hemorrhage as bleeding 24 hours to 12 weeks after delivery. Clinically worrisome uterine hemorrhage develops within 1 to 2 weeks in perhaps 1 percent of women. Such bleeding most often stems from abnormal involution of the placental site. It occasionally is caused by retention of a placental fragment or by a uterine artery pseudoaneurysm.

Rarely, retained products may undergo necrosis with fibrin deposition and neovascularization, thus forming a placental polypoid mass. Severe hemorrhage occurs in only 6 percent of these cases due to rupture of blood vessels (Marques, 2011). Sonographically, a discrete hypervascular endometrial mass that may extend into the myometrium is visualized (Fig. 36-4). As discussed in Chapter 59 (p. 1062), delayed postpartum hemorrhage may also be caused by von Willebrand disease or other inherited coagulopathies (Lipe, 2011).

In our experiences, few women with delayed hemorrhage are found to have retained placental fragments. Thus, we and others do not routinely perform curettage (Lee, 1981). Another concern is that curettage may worsen bleeding by avulsing part of the implantation site. Thus, in a stable patient, if sonographic examination shows an empty cavity, then oxytocin, methylergonovine, or a prostaglandin analogue is given. Suitable dosing is found in Table 13-3 (p. 240). Antimicrobials are added if uterine infection is suspected. If large clots are seen in the uterine cavity with sonography, then gentle suction curettage is considered. Otherwise, curettage is carried out only if appreciable bleeding persists or recurs after medical management.

URINARY TRACT

Normal pregnancy-induced glomerular hyperfiltration persists during the puerperium but returns to prepregnancy baseline by 2 weeks (Hladunewich, 2004). Parturition induces a transient rise in excretion of glomerular podocytes (Furuta, 2017). Dilated ureters and renal pelves return to their prepregnant state by 2 to 8 weeks postpartum. Because of this dilated collecting system, coupled with residual urine and bacteriuria in a traumatized bladder, symptomatic urinary tract infection remains a concern in the puerperium.

FIGURE 36-4 Sonogram of a polypoid placental mass with color Doppler applied. The mass is demarcated by the dashed white lines. Hypervascularity is seen extending from the mass into the

myometrium. Funnell and colleagues (1954) used cystoscopy immediately postpartum and described varying degrees of submucosal hemorrhage and edema. Bladder trauma is associated most closely with labor length and thus to some degree accompanies normal vaginal delivery. Postpartum, the bladder has a greater capacity and a relative insensitivity to intravesical pressure. Consequently, overdistention, incomplete emptying, and excessive residual urine are frequent (Buchanan, 2014; Mulder, 2014).

Acute urinary retention is more common with epidural or narcotic analgesia (Kandadai, 2014). The management of urinary retention is discussed later (p. 643). Stress urinary incontinence during the puerperium may occur in 5 percent of women (Wang, 2017). Much attention has been given to the potential for subsequent development of urinary incontinence and other pelvic floor disorders in the years following delivery (Colla, 2018). A more detailed discussion is found in Chapter 30 (p. 548).

PERITONEUM AND ABDOMINAL WALL

The broad and round ligaments require considerable time to recover from stretching and loosening during pregnancy. The abdominal wall remains soft and faccid as a result of ruptured elastic fibers in the skin and prolonged distention by the gravid uterus. If the abdomen is unusually lax or pendulous, an ordinary girdle is often satisfactory. An abdominal binder is another temporary measure. Several weeks are required for these structures to return to normal, and exercise aids recovery. These may be started anytime following vaginal delivery. After cesarean delivery, a 6-week interval to allow anterior abdominal wall fascia to heal and abdominal soreness to diminish is reasonable. Silvery abdominal striae commonly develop as striae gravidarum (Chap. 4, p. 55). Except for these, the abdominal wall usually resumes its prepregnancy appearance. When muscles remain atonic, however, the abdominal wall also remains lax. Marked separation of the rectus abdominis muscles—diastasis recti—may result. This separation develops from a gradual thinning and widening of the linea alba and is coupled with a general laxity of the ventral abdominal wall muscles. Importantly, musculofascial continuity and lack of a true hernia sac differentiates this from a ventral hernia (Mommers, 2017).

BLOOD AND BLOOD VOLUME

■ Hematological and Coagulation Changes

Marked leukocytosis and thrombocytosis may occur during and after labor. The white blood cell count seldom exceeds 25,000/μL, and the rise is predominantly due to granulocytes (Arbib, 2016; Sanci, 2017). A relative lymphopenia and an absolute eosinopenia is typical. Normally, during the first few postpartum days, hemoglobin concentration and hematocrit decrease moderately. If they fall much below prelabor levels, a considerable amount of blood has been lost. By the end of pregnancy, laboratory values that assess coagulation are altered (Kenny, 2015). These changes are discussed in Chapter 4 (p. 61) and listed in the Appendix (p. 1228). Many extend variably in the puerperium. For example, a markedly higher plasma fibrinogen level is maintained at least through the first week. This contributes to hypercoagulability (Chap. 55, p. 975). As one result, the pregnancy-associated risks for deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism persist in the 12 weeks following childbirth (Kamel, 2014).

■ Pregnancy Induced Hypervolemia

When the amount of blood attained by normal pregnancy hypervolemia is lost as postpartum hemorrhage, the woman almost immediately regains her nonpregnant blood volume (Chap. 42, p. 732). If less has been lost at delivery, blood volume generally nearly returns to its nonpregnant level by 1 week after delivery. Cardiac output usually remains elevated for 24 to 48 hours postpartum and declines to nonpregnant values by 10 days (Robson, 1987). Heart rate changes follow this pattern, and blood pressure similarly returns to nonpregnant values (Fig. 36-5). Correspondingly, systemic vascular resistance remains in the lower range characteristic of pregnancy for 2 days postpartum and then begins to steadily rise to normal nonpregnant values (Hibbard, 2015). Despite this, Morris and coworkers (2015) found that reduced arterial stiffness persists following pregnancy. They suggest a significant favorable effect of pregnancy on maternal cardiovascular remodeling. This may represent a mechanism by which preeclampsia risk is reduced in subsequent pregnancies.

■ Postpartum Diuresis

Normal pregnancy is associated with appreciable extracellular sodium and water retention, and postpartum diuresis is a physiological reversal of this process. Chesley and associates (1959) demonstrated an approximate 2 liter decline in sodium space during the first week postpartum. This corresponds with loss of residual pregnancy hypervolemia. In preeclampsia, pathological retention of fluid antepartum and then its normal diuresis postpartum may be prodigious (Chap. 41, p. 724).

Postpartum diuresis results in a relatively rapid weight loss of 2 to 3 kg, which is additive to the 5 to 6 kg incurred by delivery and normal blood loss. Weight loss from pregnancy itself likely peaks by the end of the second week postpartum.

Any residual weight compared with prepregnancy values probably represents fat stores that will persist.

LACTATION AND BREASTFEEDING

■ Breast Anatomy and Secretory Products

Each mature mammary gland or breast is composed of 15 to 25 lobes. They are arranged radially and are separated from one another by varying amounts of fat. Each lobe consists of several lobules, which in turn are composed of numerous alveoli. Each alveolus is provided with a small duct that joins others to form a single larger duct for each lobe (Fig. 36-6). These lactiferous ducts open separately on the nipple, where they may be distinguished as small but distinct orifices. Te alveolar secretory epithelium synthesizes the various milk constituents.

After delivery, the breasts begin to secrete colostrum, which is a deep-yellow liquid. It usually can be expressed from the nipples by the second postpartum day. Compared with mature milk, colostrum is rich in immunological components and contains more minerals and amino acids (Y de Vries, 2018). It also has more protein, much of which is globulin, but less sugar and fat. Secretion persists for 5 to 14 days, with gradual conversion to mature milk by 4 to 6 weeks. The colostrum content of immunoglobulin A (IgA) offers the newborn protection against enteric pathogens. Other host resistance Factors found in colostrum and milk include complement, macrophages, lymphocytes, lactoerrin, lactoperoxidase, and lysozymes.

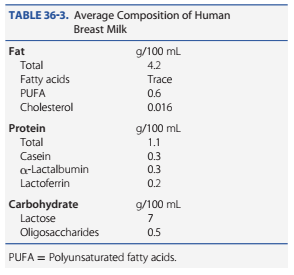

A lactating mother produces upwards of 600 mL of milk daily, and maternal gestational weight gain has little impact on its quantity or quality. Mature milk is a complex and dynamic biological fluid that includes fat, proteins, carbohydrates, bioactive factors, minerals, vitamins, hormones, and many cellular products (Table 36-3). The contents and concentrations of human milk change even during a single feed and are influenced by maternal diet and by newborn age, health, and needs. Milk is isotonic with plasma, and lactose accounts for half of the osmotic pressure. Essential amino acids are derived from blood, and nonessential amino acids are derived in part from blood or synthesized in the mammary gland. Most milk proteins are unique and include alpha-lactalbumin, beta-lactoglobulin, and casein. Fatty acids are synthesized in the alveoli from glucose and are secreted by an apocrine-like process. Variable amounts of most vitamins are found in human milk. Vitamin K is virtually absent, and thus, an intramuscular dose is given to the newborn (Chap. 33, p. 606). Vitamin D content is low, and newborn supplementation is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2017).

Whey is milk serum and contains large amounts of interleukin-6 and other chemokines (Polat, 2016). Human milk has a whey-to-casein ratio of 60:40, which is considered ideal for absorption. Prolactin appears to be actively secreted into breast milk. Epidermal growth factor has been identified, and because it is not destroyed by gastric proteolytic enzymes, it may be absorbed to promote growth and maturation of newborn intestinal mucosa. Other critical components in human milk include melatonin and oligosaccharides.

FIGURE 36-6 Schematic of the alveolar and ductal system during lactation. Note the myoepithelial fibers (M) that surround the outside of the uppermost alveolus. The secretions from the glandular elements are extruded into the lumen of the alveoli (A) and ejected by the myoepithelial cells into the ductal system (D), which empties through the nipple. Arterial blood supply to the alveolus is identified by the upper right arrow and venous drainage by the arrow beneath.

■ Lactation Endocrinology

Te precise humoral and neural mechanisms involved in lactation are complex. Progesterone, estrogen, and placental lactogen, as well as prolactin, cortisol, and insulin, appear to act in concert to stimulate the growth and development o the milksecreting apparatus (Stuebe, 2014). With delivery, the maternal serum levels o progesterone and estrogen decline abruptly and prooundly. Tis drop removes the inhibitory inuence o progesterone on alpha-lactalbumin production and stimulates

lactose synthase to raise milk lactose levels. Progesterone withdrawal also allows prolactin to act unopposed in its stimulation o alpha-lactalbumin production. Activation o calcium-sensing

receptors in mammary epithelial cells downregulates parathyroid hormone–related protein (PHrP) and increases calcium transport into milk (Vanhouten, 2013). Serotonin also is produced in mammary epithelial cells and has a role in maintaining milk production (Collier, 2012).

Te posterior pituitary secretes oxytocin in pulsatile ashion. Tis stimulates milk expression rom a lactating breast by causing contraction o myoepithelial cells in the alveoli and small milk ducts (see Fig. 36-6). Milk ejection, or letting down, is a reex initiated especially by suckling, which stimulates the posterior pituitary to liberate oxytocin. Te reex may even be provoked by an inant cry and can be inhibited by maternal right or stress (Stuebe, 2014).

■ Immunological Consequences of Breastfeeding

Human milk contains several protective immunological substances, including secretory IgA and growth actors. Te antibodies in human milk are specically directed against maternal environmental antigens such as Escherichia coli (Macpherson, 2017). According to the CDC, breasteeding decreases the incidence o ear, respiratory, and gastrointestinal inections; necrotizing enterocolitis; and sudden inant death syndrome (SIDS) (Perrine, 2015). Breasteeding is especially important or immunity in preterm inants (Lewis, 2017).

Much attention has been directed to the role o maternal breast milk lymphocytes in neonatal immunological processes. Milk contains both and B lymphocytes, but the lymphocytes appear to dier rom those ound in blood. Specically, milk lymphocytes are almost exclusively composed o cells that exhibit specic membrane antigens. Tese memory cells appear to be an avenue or the neonate to benet rom the maternal immunological experience.

■ Lactation

Te ideal time to begin breasteeding is within an hour o birth. Human milk is ideal ood or newborns in that it provides age-specic nutrients, immunological actors, and antibacterial substances. Milk also contains actors that act as biological signals or promoting cellular growth and dierentiation. A list o the advantages o breasteeding is shown in Table 36-4. Lactation has long-term benets or both the mother and the inant. For example, women who breasteed have a lower risk o breast and reproductive cancer. Children who were breast- ed have higher adult intelligence scores independent o a wide range o possible conounding actors (Jong, 2012; Kramer, 2008). In the short term, lactation is associated with less postpartum weight retention (Baker, 2008). In addition, rates o SIDS are signicantly lower among breast-ed inants. Bartek and colleagues (2013) estimate that a 90-percent breasteeding rate or 12 months would save more than $3 billion annually

in excess inant and maternal morbidity costs. For all these reasons, the American Academy o Pediatrics and American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2017) support the World Health Organization (2011) recommendations o exclusive breasteeding or up to 6 months.

Currently, 55 percent o women breasteed at 6 months compared with a Healthy People 2020 goal o 61 percent. (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2018b).

Te Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative is an international program to raise rates o exclusive breasteeding and to extend its duration. It is based on the World Health Organization (2018) Ten Steps to Successful Breastfeeding (Table 36-5). Worldwide, almost 20,000 hospitals are deemed “baby-riendly,” however, only 15 to 20 percent o hospitals in the United States are so designated (Baby-Friendly USA, 2018; Perrine, 2015). In a large population-based study done in the United States, ewer than two thirds o term neonates were exclusively breasted at the time o discharge (McDonald, 2012). By 3 months, according to the CDC, less than hal o these inants are exclusively breasted (Olaiya, 2016).

Various individual resources are available online or lactating mothers rom the American Academy o Pediatrics (www. aap.org) and La Leche League International (www.llli.org).

■ Breast Care

Te nipples require little attention other than cleanliness and attention to skin ssures. Fissured nipples render lactation

TABLE 36-4. Advaags f Brasfdg

Nutritional

Immunological

Developmental

Psychological

Social

Economic

Environmental

Optimal growth and development

Decrease risks for acute and chronic diseases

The Puerperium 641

CHAPTER 36

painul, and they may have a deleterious inuence on milk production. Tese cracks also provide a portal o entry or pyogenic bacteria. Because dried milk is likely to accumulate and irritate the nipples, washing the areola with water and mild soap is helpul beore and ater nursing. When the nipples are irritated or ssured, some recommend topical lanolin and a nipple shield or 24 hours or longer (Dennis, 2014). I ssuring is severe, the newborn should not be permitted to nurse on the aected side. Instead, the breast is emptied regularly with a pump until the lesions are healed.

Poor latching o the neonate to the breast can create such ssures. For example, the newborn may take into its mouth only the nipple, which is then is orced against the hard palate during suckling. Ideally, the nipple and areola are both taken in to evenly distribute suckling orces. Moreover, the orce o the hard palate against the lactierous sinuses aids their efcient emptying, while the nipple is thereby positioned closer to the sot palate.

■ Breastfeeding Contraindications

Lactation is contraindicated in women who take street drugs or do not control their alcohol use; have an inant with galactosemia; have human immunodeciency virus (HIV) inection; have active, untreated tuberculosis; take certain medications; or are undergoing breast cancer treatment (American Academy o Pediatrics, 2017). Breasteeding has been recognized or some time as a mode o HIV transmission and is proscribed in developed countries in which adequate nutrition is otherwise available (Chap. 68, p. 1222). Other viral inections do not contraindicate lactation. For example, with maternal cytomegalovirus inection, both virus and antibodies are present in breast milk. And, although hepatitis B virus is excreted in milk, breasteeding is not contraindicated i hepatitis B immune globulin is given to the newborns o aected mothers. Maternal hepatitis C inection is not a contraindication because breasteeding has not been shown to transmit inection. Women with active herpes simplex virus may suckle their inants i there are no breast lesions and i particular care is directed to hand washing beore nursing. From the CDC (2021a), those with COVID-19 should wear a mask and practice hand-hygiene.

■ Drugs Secreted in Milk

Most drugs given to the mother are secreted in breast milk, although the amount ingested by the inant typically is small. Factors inuencing drug excretion include plasma concentration, degree o protein binding, plasma and milk pH, degree o ionization, lipid solubility, and molecular weight (Rowe,

2013). Te ratio o drug concentration in breast milk to that in maternal plasma is the milk-to-plasma drug-concentration ratio. Ideally, to minimize inant exposure, medication selection avors drugs with a shorter hal-lie, poorer oral absorption, and lower lipid solubility. I multiple daily drug doses are required, each is taken by the mother after the closest eed. Single dailydosed drugs may be taken just beore the longest inant sleep interval—usually at bedtime.

Only a ew drugs are absolutely contraindicated while breast- eeding (American Academy o Pediatrics and American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017). Cytotoxic drugs may

interere with cellular metabolism and potentially cause immune suppression or neutropenia, aect growth, and at least theoretically, increase the childhood cancer risk. Examples include cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine, doxorubicin, methotrexate, and mycophenolate (Briggs, 2017). I a medication presents a concern, its importance should be ascertained. A provider can also seek a saer alternative or determine i neonatal exposure can be minimized i the medication dose is taken immediately ater each breasteeding session. Last, recreational drugs such as marijuana and alcohol should be avoided (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017c; Metz, 2018). Data on individual drugs are available through the National Institutes o Health website, LactMed, which can be ound at www.ncbi.

nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/.

Radioactive isotopes o copper, gallium, indium, iodine, sodium, and technetium rapidly appear in breast milk. Consultation with a nuclear medicine specialist is recommended beore perorming a diagnostic study with these isotopes (Chap. 49, p. 875). Ideally, a radionuclide with the shortest excretion time in breast milk is selected. Te mother should pump her breasts beore the study and store enough milk in a reezer to eed the inant. Ater the study, she should pump her breasts to maintain milk production but discard all milk produced during

TABLE 36-5. t Sps Sussful Brasfdg

1. Have a written breastfeeding policy that is regularly communicated to all health-care staff

2. Train all staff in skills necessary to implement this policy

3. Inform all pregnant women about the benefits and management of breastfeeding

4. Help mothers initiate breastfeeding within an hour of birth

5. Show mothers how to breastfeed and how to sustain lactation, even if they should be separated from their infants

6. Feed newborns nothing but breast milk, unless medically indicated, and prioritize donor breast milk when

supplementation is needed

7. Practice rooming-in, which allows mothers and newborns to remain together 24 hours a day

8. Encourage breastfeeding on demand

9. Give no artificial pacifiers to breastfeeding newborns

10. Help start breastfeeding support groups and refer mothers to them

Adapted from the World Health Organization, 2018.

the time that radioactivity is present. Tis ranges rom 15 hours to 2 weeks, depending on the isotope used. Importantly, radioactive iodine concentrates and persists in the thyroid. Its special considerations are discussed in Chapter 66 (p. 1174). For magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, breasteeding should not be interrupted ater gadolinium administration (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017a).

■ Breast Engorgement

This is common in women who do not breastfeed. It is typified by milk leakage and breast pain, which peak 3 to 5 days ater delivery. Up to hal o aected women require analgesia or breast pain relie, and as many as 10 percent report severe pain or up to 14 days.

Evidence is insufcient to rmly support any specic treatment (Mangesi, 2016). Tat said, breasts can be supported with well-tting brassiere, breast binder, or sports bra. Cool packs and oral analgesics or 12 to 24 hours aid discomort. Pharmacological or hormonal agents in general are not recommended to suppress lactation.

Fever caused by breast engorgement was common beore the renaissance o breasteeding. In one study, 13 percent o puerperas with engorgement had ever ranging rom 37.8 to 39°C (Almeida, 1986). Fever seldom persists or longer than 4 to 16 hours. Te incidence and severity o engorgement and o the ever associated with it are much lower i women breasteed. Other causes o ever, especially those due to inection, must be excluded. Mastitis is inection o the mammary parenchyma and is relatively common in lactating women (Chap. 37, p. 659).

■ Other Lactation Issues

With inverted nipples, lactierous ducts open directly into a depression at the center o the areola. With these depressed nipples, nursing is difcult. I the depression is not deep, milk sometimes can be drawn out by a breast pump. I instead the nipple is greatly inverted, daily attempts are made during the last ew months o pregnancy to draw or “tease” the nipple out with the ngers.

Extra breasts—polymastia, or extra nipples—polythelia, may develop along the ormer embryonic mammary ridge. Also termed the milk line, this line extends rom the axilla to the groin bilaterally. In some women, rests o accessory breast tissue can be ound in the mons pubis or vulva (Wagner, 2013). In the general population, the incidence o accessory breast tissue ranges rom 0.22 to 6 percent (Loukas, 2007). Tese breasts may be so small as to be mistaken or pigmented moles, or i without a nipple, or lymphadenopathy or lipoma. Polymastia has no obstetrical signicance, although occasionally enlargement o these accessory breasts during pregnancy or engorgement postpartum may result in patient discomort and anxiety.

Galactocele is a milk duct that becomes obstructed by inspissated secretions. Te amount is ordinarily limited, but an excess may orm a uctuant mass—a galactocele—that can cause pressure symptoms and have the appearance o an abscess. It may resolve spontaneously or require aspiration.

Among individuals, the volume o milk secreted varies markedly. Tis depends not on general maternal health but on breast glandular development. Rarely, there is complete lack o mammary secretion—agalactia. Occasionally, mammary secretion is excessive—polygalactia.

Laa-Assad osprss

Tis is a rare disorder o unknown etiology that may be associated with severe back pain or vertebral ractures (Li, 2018; Zhang, 2017). Preliminary studies indicate that bisphosphonates are eective in its management. However, or almost all women, lactation is not associated with later-onset osteoporosis (Crandall, 2017). Pregnancy-associated osteoporosis is discussed in Chapter 61 (p. 1100).

HOSPITAL CARE

For 2 hours ater delivery, blood pressure and pulse are taken every 15 minutes, at minimum. emperature is assessed every 4 hours or the rst 8 hours and then at least every 8 hours subsequently (American Academy o Pediatrics and American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017). I regional analgesia or general anesthesia was used or labor or delivery,

the mother should be observed in an appropriately equipped and staed recovery area. Expected anesthesia recovery and complications are described in Chapter 25 (p. 473).

Because the likelihood o signicant hemorrhage is greatest immediately postpartum, vaginal bleeding is closely monitored. Te uterine undus is palpated to ensure that it is well contracted. I relaxation is detected, the uterus should be massaged through the abdominal wall until it remains contracted. Uterotonics also are sometimes required. Blood may accumulate within the uterus without external bleeding. Tis may be detected early by uterine enlargement during undal palpation in the rst postdelivery hours. Postpartum hemorrhage is discussed in Chapter 41.

Early ambulation within a ew hours ater delivery is encouraged. An attendant should be present or at least the rst time, in case the woman becomes syncopal. Te many conrmed advantages o early ambulation include ewer bladder complications, less requent constipation, and reduced rates o puerperal venous thromboembolism. As discussed, deep-vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism are common in the puerperium. In our audits o puerperal women at Parkland Hospital, the requency o venous thromboembolism is extremely low. We attribute this to early ambulation. Risk actors and other measures to diminish the requency o thromboembolism are discussed in Chapter 55 (p. 984).

Diets need not be restricted or women who give birth vaginally. Generally, two hours ater uncomplicated vaginal delivery, a woman is allowed to eat. With lactation, the level o calories and protein consumed during pregnancy is increased slightly as recommended by the Food and Nutrition Board o the National Research Council (Chap. 10, p. 184). I the mother does not breasteed, dietary requirements are the same as or a nonpregnant woman. We recommend oral iron supplementation or at least 3 months ater delivery and hematocrit evaluation at the rst postpartum visit.

As noted earlier, proound drops in estrogen levels ollow removal o the placenta. Reminiscent o the menopause, postpartum women may experience hot ushes, especially at night. Importantly, the patient’s temperature is assessed to di- erentiate these physiological vasomotor events rom inection. In women with migraines, dramatic hypoestrogenism may trigger headaches. Importantly, severe headaches should be di- erentiated rom postdural puncture headache or hypertensive

complications. Care varies depending on headache severity.

Mild headaches may respond to analgesics such as ibuproen or acetaminophen. For more severe headaches, oral or systemic narcotics can be used. Alternatively, a triptan, such as sumatriptan (Imitrex), can relieve headaches by causing intracranial vasoconstriction, and it is breasteeding compatible.

■ Perineal Care

Te woman is instructed to clean the vulva rom anterior to posterior—the vulva toward the anus. A cool pack applied to the perineum may help reduce edema and discomort during the rst 24 hours i there is a perineal laceration or an episiotomy. Most women also appear to obtain a measure o relie rom the periodic application o a local anesthetic spray. Severe perineal, vaginal, or rectal pain always warrants careful inspection and palpation. Severe discomort usually indicates a problem,

such as a hematoma within the rst day or so and inection ater the third or ourth day (Chap. 37, p. 657 and Chap. 42, p. 740). Beginning approximately 24 hours ater delivery, moist heat as provided by warm sitz baths can reduce local discomort. ub bathing ater uncomplicated delivery is allowed.

Te episiotomy incision normally is rmly healed and nearly asymptomatic by the third week.

Rarely, the cervix, and occasionally a portion o the uterine body, may protrude rom the vulva ollowing delivery. Tis is accompanied by variable degrees o anterior and posterior vaginal wall prolapse. Symptoms include a palpable mass at or past the introitus, voiding difculties, or pressure. Puerperal procidentia typically improves with time as the weight o the uterus lessens with involution. As a temporizing measure or pronounced prolapse, the uterus can be replaced and held in position with a space-lling pessary, such as a donut type. Rectal veins are oten congested at term. Trombosis o these hemorrhoids is common and may be promoted by second-stage pushing. reatment includes topically applied anesthetics, warm soaks, and stool-sotening agents. Nonprescription topical preparations containing corticosteroids, astringents, or phenylephrine are oten used. However, no randomized studies support their efcacy compared with symptomatic care.

■ Bladder Function

In most delivery units, intravenous uids are inused during labor and or an hour or so ater vaginal delivery. Oxytocin, in doses that have an antidiuretic eect, is typically inused postpartum, and rapid bladder lling is common. Moreover, both bladder sensation and capability to empty spontaneously

may be diminished by components o the labor and delivery process. Tus, urinary retention and bladder overdistention is common in the early puerperium. Te incidence in more than 5500 women studied with a bladder scanner was 5 percent (Buchanan, 2014). It is much less clinically. Risk actors that increased the likelihood o retention include primiparity, epidural analgesia, cesarean delivery, perineal lacerations, operative vaginal delivery, catheterization during labor, and prolonged second-stage labor (Stephansson, 2016; Wang, 2017). Prevention o bladder overdistention demands observation ater delivery to ensure that the bladder does not overll and that it empties adequately with each voiding. Te enlarged bladder can be palpated suprapubically, or it is evident abdominally indirectly as it elevates the undus above the umbilicus. Most currently use an automated sonography system to detect high bladder volumes and thus postpartum urinary retention (Buchanan, 2014).

I a woman has not voided within 4 hours ater delivery, it is likely that she cannot. I she has trouble voiding initially, she also is likely to have urther trouble. First, an examination or perineal and genital-tract hematomas is completed, as these may be contributory. With an overdistended bladder, an indwelling catheter should be placed and let until the actors causing retention have abated. Even without a demonstrable cause, it usually is best to leave the catheter in place or at least 24 hours. Tis prevents recurrence and allows recovery o normal bladder tone and sensation.

When the catheter is removed, a voiding trial is completed to demonstrate an ability to void appropriately. I a woman cannot void ater 4 hours, urine volumes are measured sonographically.

I more than 200 mL, the bladder is not unctioning appropriately, and the catheter is replaced and remains or another 24 hours. Although rare, i retention persists ater a second voiding trial, an indwelling catheter and leg bag can be elected, and the patient returns in 1 week or an outpatient voiding trial. In a study o 27 women with a protracted course, all resumed normal voiding by 3 weeks postpartum (Mevorach Zussman, 2020).

During a voiding trial, i less than 200 mL o urine is obtained, the catheter can be removed and the bladder subsequently monitored clinically and sonographically as described earlier. Harris and coworkers (1977) reported that 40 percent o such women develop bacteriuria, and thus a single dose or short course o antimicrobial therapy against uropathogens is reasonable ater the catheter is removed.

■ Pain, Mood, and Cognition

Discomort and its causes ollowing cesarean delivery are considered in Chapter 30 (p. 565). During the rst ew days ater vaginal delivery, the mother may be uncomortable because o aterpains, episiotomy and lacerations, breast engorgement, and at times, postdural puncture headache. Mild analgesics containing codeine, ibuproen, or acetaminophen, preerably in combinations, are given as requently as every 4 hours during the rst ew days.

It is important to screen the postpartum woman or depression (Mangla, 2019). Commonly, mothers exhibit some degree o depressed mood a ew days ater delivery. ermed postpartum blues, this likely is the consequence o several actors. Tese include the emotional letdown that ollows the excitement and ears experienced during pregnancy and delivery, discomorts o the early puerperium, atigue rom sleep deprivation, anxiety over the ability to provide appropriate newborn care, and body image concerns. In most women, eective treatment includes anticipation, recognition, and reassurance. Tis disorder is usually mild and sel-limited to 2 to 3 days, although it sometimes lasts or up to 10 days. Should these moods persist or worsen, an evaluation or symptoms o major depression is done (Chap. 64, p. 1145).

Last, postpartum hormonal changes in some women may aect brain unction. Bannbers and colleagues (2013) observed a unctional decline in executive unction in postpartum women.

■ Neuromusculoskeletal Problems

obsral nurpahs

Pressure on branches o the lumbosacral nerve plexus during labor may maniest as complaints o intense neuralgia or cramplike pains extending down one or both legs as soon as the head descends into the pelvis. I the nerve is injured, pain may continue ater delivery, and variable degrees o sensory loss or muscle paralysis can result. In some cases, there is ootdrop, which can be secondary to injury at the level o the lumbosacral plexus, sciatic nerve, or common bular (peroneal) nerve (Bunch, 2014). Components o the lumbosacral plexus cross the pelvic brim and can be compressed by the etal head or by orceps. Te common bular nerves may be externally compressed when the legs are positioned in stirrups, especially during prolonged second-stage labor.

Obstetrical neuropathy is relatively inrequent. Evaluation o more than 6000 puerperas ound that approximately 1 percent had a conrmed nerve injury (Wong, 2003). Lateral emoral

cutaneous neuropathies were the most common (24 percent), ollowed by emoral neuropathies (14 percent). A motor decit accompanied a third o injuries. Nulliparity, prolonged secondstage labor, and pushing or a long duration in the semi-Fowler position were risk actors. Te median duration o symptoms was 2 months, and the range was 2 weeks to 18 months.

Injury o the iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves may occur with cesarean delivery (Rahn, 2010; Yazici Yilmaz, 2018). We have rarely encountered lumbar arachnoiditis ollowing epidural analgesia causing severe bilateral neuropathic pain.

Musulsklal ijurs

Pain in the pelvic girdle, hips, or lower extremities may ollow stretching or tearing injuries sustained at normal or di- cult delivery. MR imaging is oten inormative when clinical examination is normal (Miller, 2015). Most injuries resolve with antiinammatory agents and physical therapy. Rarely, there may be septic pyomyositis such as with iliopsoas muscle abscess (Nelson, 2010; Young, 2010).

Separation o the symphysis pubis or one o the sacroiliac synchondroses during labor leads to pain and marked intererence with locomotion (Fig. 36-7). Estimates o the requency o this event vary widely rom 1 in 600 to 1 in 30,000 deliveries (Reis, 1932; aylor, 1986). In our experiences, symptomatic separations are uncommon. Teir onset o pain is oten acute during delivery, but symptoms may maniest either antepartum or up to 48 hours postpartum (Snow, 1997). Radiography is typically used or evaluation. Te normal distance o the symphyseal joint is 0.4 to 0.5 cm, and symphyseal separation >1 cm is diagnostic or diastasis. reatment is generally conservative, with rest in a lateral decubitus position and an appropriately tted pelvic binder (Lasbleiz, 2017). Surgery is

occasionally necessary in some symphyseal separations >4 cm (Kharrazi, 1997). Te recurrence risk is high in subsequent pregnancies, and Culligan and associates (2002) recommend consideration or cesarean delivery.

In rare cases, ractures o the sacrum or pubic ramus are caused by even uncomplicated deliveries (Alonso-Burgos, 2007; Speziali, 2015). Discussed in Chapter 61 (p. 1100), the latter is more likely with osteoporosis associated with heparin or corticosteroid therapy. In rare but serious cases, bacterial osteomyelitis— osteitis pubis—can be devastating. Laword and coworkers (2010) reported such a case that caused massive vulvar edema.

■ Immunizations

Te D-negative woman who is not isoimmunized and whose newborn is D-positive is given 300 μg o anti-D immune globulin shortly ater delivery (Chap. 18, p. 357). Women who are not already immune to rubella or varicella are excellent candidates or vaccination beore discharge (Swamy, 2015). Tose who have not received a tetanus/diphtheria (dap/d) or inuenza vaccine should be given these (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017e) (able 10-7, p. 189). Te CDC (2021b) recommends the COVID-19 vaccine, and includes breasteeding women. Morgan and colleagues (2015) reported that implementation o a best-practices alert in the electronic medical record was associated with a dap immunization rate o 97 percent at Parkland Hospital.

When permissible by law, the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2019) recommends standing orders or indicated immunizations.

FIGURE 36-7 Pubic symphyseal separation found on the first postpartum day following vaginal delivery of a 2840-g newborn. The patient had pain over the pubic bone and pain with ambulation. A shuffling gait was noted, and she had difficulty with leg elevation when supine. The patient was treated with physical therapy and analgesics. A pelvic binder was applied, and a rolling walker was provided. She improved quickly and was discharged home on postpartum day 5.

CHAPTER 36

■ Contraception

During the hospital stay, a concerted eort is made to provide amily planning education. Various orms o contraception are discussed throughout Chapter 38 and sterilization procedures in Chapter 39. Te immediate puerperium is an ideal time or consideration o long-acting reversible contraception—LARC (American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017b).

Women not breasteeding have return o menses usually within 6 to 8 weeks. At times, however, it is difcult clinically to assign a specic date to the rst menstrual period ater delivery. A minority o women bleed small to moderate amounts intermittently starting soon ater delivery. Ovulation occurs at a mean o 7 weeks but ranges rom 5 to 11 weeks (Perez, 1972). Tat said, ovulation beore 28 days has been described (Hytten, 1995). Tus, conception is possible during the early puerperium.

Women who become sexually active during the puerperium and who do not desire to conceive should initiate contraception. Kelly and associates (2005) reported that by the third month postpartum, 58 percent o adolescents had resumed sexual intercourse, but only 80 percent o these were using contraception. Because o this, many recommend LARC during the puerperium. Women who breasteed ovulate much less requently compared with those who do not, but variation is great. iming o ovulation depends on individual biological variation and the intensity o breasteeding. Lactating women may rst menstruate as early as the second or as late as the 18th month ater delivery. Campbell and Gray (1993) analyzed daily urine specimens in 92 lactating women. Breasteeding in general delays resumption o ovulation, although it does not invariably orestall it.

Other ndings in their study included the ollowing:

1. Resumption o ovulation was requently marked by return o

normal menstrual bleeding.

2. Breasteeding episodes lasting 15 minutes seven times daily

delayed ovulation resumption.

3. Ovulation can occur without bleeding.

4. Bleeding can be anovulatory.

5. Te risk o pregnancy in breasteeding women was approximately 4 percent per year.

For the breasteeding woman, progestin-only contraceptives, such as progestin pills, depot medroxyprogesterone, or progestin implants or IUDs, do not aect the quality or quantity o milk.

Not available in the United States, success with the progesteronereleasing vaginal ring also has been described (Carr, 2016). Tese may be initiated any time during the puerperium. Estrogenprogestin contraceptives likely reduce the quantity o breast milk, but under the proper circumstances, they too can be used by lactating women. Tese hormonal methods are discussed in

Chapter 38 (p. 671).

■ Hospital Discharge

Following uncomplicated vaginal delivery, hospitalization is seldom warranted or more than 48 hours. Hospital stay length ollowing labor and delivery is now regulated by ederal law (Chap. 32, p. 596). Currently, the norms are hospital stays up to 48 hours ollowing uncomplicated vaginal delivery and up to 96 hours ollowing uncomplicated cesarean delivery ( American Academy o Pediatrics and American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2017; Blumeneld, 2015). Earlier hospital discharge is acceptable or appropriately selected women i they desire it. A woman should receive instructions concerning anticipated normal physiological puerperal changes, including lochia patterns, weight loss rom diuresis, and milk let-down. She also should receive instructions concerning ever, excessive vaginal bleeding, or leg pain, swelling, or tenderness. Persistent headaches, shortness o breath, or chest pain warrant immediate concern.

HOME CARE

■ Coitus

No evidence-based data guide resumption o coitus ater delivery, and practices are individualized (Minig, 2009). Ater 2 weeks, coitus may be resumed based on desire and comfort. Wallwiener and colleagues (2017) reported that 60 percent o women resumed sexual activity by 1 week and 80 percent by 4 months. Tey also reported that a third o these women had sexual dysunction. Intercourse too soon may be unpleasant, i not pain- ul, and this may be related to episiotomy incisions or perineal lacerations. In a study o women without an episiotomy, only 0.4 percent o those with a rst- or second-degree tear had dyspareunia (Ventolini, 2014). Conversely, in primiparas with an episiotomy, 67 percent had sexual dysunction at 3 months, 31 percent at 6 months, and 15 percent at 12 months (Chayachinda, 2015). Only 40 percent o women with an anal sphincter injury had resumed intercourse by 12 weeks (LeaderCramer, 2016). Last, dyspareunia was also common ollowing cesarean delivery (McDonald, 2015).

Postpartum, the vulvovaginal epithelium is thin, and very little lubrication ollows sexual stimulation. Tis stems rom the hypoestrogenic state ollowing delivery, which lasts until ovulation resumes. It may be particularly problematic in breasteeding women who are hypoestrogenic or many months postpartum (Palmer, 2003). For treatment, small amounts o topical estrogen cream can be applied daily or several weeks to vulvar tissues. Additionally, vaginal lubricants may be used with coitus.

Tis same thinning o the vulvovaginal epithelium can lead to dysuria. opical estrogen can again be oered once cystitis is excluded.

■ FollowUp Care

By discharge, women who had an uncomplicated vaginal delivery can resume most activities, including bathing, driving, and household unctions. Despite this, ulman and Fawcett (1988) reported that only hal o mothers regained their usual level o energy by 6 weeks. Women who delivered vaginally were twice as likely to have normal energy levels at this time compared with those with a cesarean delivery. Ideally, the care and nurturing o the inant should be provided by the mother with ample help rom the ather. Jimenez and Newton (1979) tabulated cross-cultural inormation on 202 societies rom various international geographical regions. Following childbirth, most societies did not restrict work activity, and approximately hal expected a return to ull duties within 2 weeks. Wallace and coworkers (2013) reported that 80 percent o women who worked during pregnancy resume work by 1 year ater delivery.

Discussed on page 634, during this ourth trimester, the American College o Obstetricians and Gynecologists (2018a) recommends a comprehensive visit within 12 weeks ater delivery. Tis has proved quite satisactory to identiy abnormalities beyond the immediate puerperium and to initiate contraceptive practices

Nhận xét

Đăng nhận xét