Female Genital Tract

BS. Nguyễn Hồng Anh

The vulva

The vulva (or pudendum) is the term applied to the female external genitalia.

The labia majora are the prominent hair-bearing folds extending back from the mons pubis to meet posteriorly in the midline of the perineum. They are the equivalent of the male scrotum. The labia minora lie between the labia majora as lips of soft skin which meet posteriorly in a sharp fold, the fourchette. Anteriorly, they split to enclose the clitoris, forming an anterior prepuce and posterior frenulum.

The vestibule is the area enclosed by the labia minora and contains the urethral orifice (which lies immediately behind the clitoris) and the vaginal orifice.

The vaginal orifice is guarded in the virgin by a thin mucosal fold, the hymen, which is perforated to allow the egress of the menses, and may have an annular, semilunar, septate or cribriform appearance. Rarely, it is imperforate and menstrual blood distends the vagina (haematocolpos). At first coitus the hymen tears, usually posteriorly or posterolaterally, and after childbirth nothing is left of it but a few tags termed carunculae myrtiformes.

Bartholin’s glands (the greater vestibular glands) are a pair of lobulated, pea-sized, mucus-secreting glands lying deep to the posterior parts of the labia majora. They are impalpable when healthy but become obvious when inflamed or distended. Each drains by a duct 1 in (2.5 cm) long which

CLINICAL FEATURES

1 The fossa contains coarsely lobulated fat. It is important to note that the ischio-anal fossae communicate with each other behind the anal canal – infection in one may therefore pass to the other. Infection of this space may occur from boils or abrasions of the perianal skin, or from lesions within the rectum and anal canal, especially infection of the branched anal glands, approximately six in number, which lie immediately above the valves of Ball (see page 90 and Fig. 62). Occasionally, it may follow from pelvic infection bursting through levator ani or, rarely, via the bloodstream. The fossa contains no important structures and can, therefore, be incised without fear when infected.

2 The pudendal nerves can be blocked in Alcock’s canal on either side to give useful regional anaesthesia in obstetrical forceps delivery (Fig. 97 and see page 274).148 The abdomen and pelvis opens into the groove between the hymen and the posterior part of the labium minus.

Anteriorly, each gland is overlapped by the bulb of the vestibule – a mass of cavernous erectile tissue equivalent to the bulbus spongiosum of the male. This tissue passes forwards, under cover of bulbospongiosus, around the sides of the vagina to the roots of the clitoris.

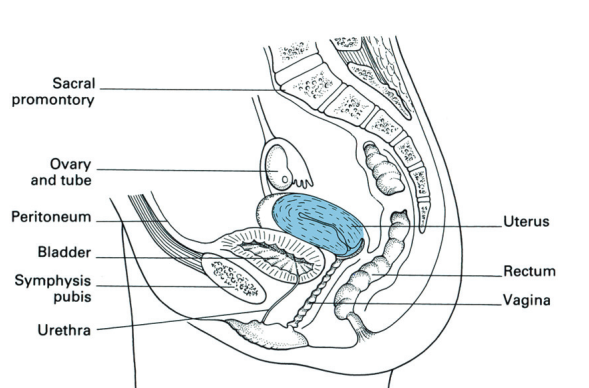

Fig. 99 Sagittal section of the uterus and its relations.

CLINICAL FEATURES

At childbirth the introitus may be enlarged by making an incision in the perineum (episiotomy). This starts at the fourchette and extends posterolaterally on the right side for 1.5in (3cm). The skin, vaginal epithelium, subcutaneous fat, perineal body and superficial transverse perineal muscle are incised. After delivery the episiotomy is carefully sutured in layers.

The vagina (Fig. 99)

The vagina surrounds the cervix of the uterus, then passes downwards and forwards through the pelvic floor to open into the vestibule. The cervix projects into the anterior part of the vault of the vagina so that the continuous gutter surrounding the cervix is shallow anteriorly (where the vaginal wall is 3in (7.5cm) in length) and is deep posteriorly (where the wall is 4in (10cm) long). This continuous gutter is, for convenience of description, divided into the anterior, posterior and lateral fornices.

Relations

• Anteriorly – the base of the bladder and the urethra (which is embedded in the anterior vaginal wall).

• Posteriorly – from below upwards, the anal canal (separated by the perineal body), the rectum and then the peritoneum of the pouch of Douglas, which covers the upper quarter of the posterior vaginal wall.

• Laterally – levator ani, pelvic fascia and the ureters, which lie immediately above the lateral fornices.

The amateur abortionist (or inexperienced gynaecologist) without a knowledge of anatomy fails to realize that the uterus passes upwards and forwards from the vagina; he pushes the instrument or IUCD (intra-uterine contraceptive device), with the intention of inserting the device in the cervix, directly backwards through the posterior fornix. To make matters worse, this is the only part of the vagina which is covered by peritoneum; the peritoneal cavity is thus entered and peritonitis follows.

Blood supply

Arterial supply is from the internal iliac artery via its vaginal, uterine, internal pudendal and middle rectal branches. A venous plexus drains via the vaginal vein into the internal iliac vein.

Lymphatic drainage (see Fig. 103)

• Upper third to the external and internal iliac nodes.

• Middle third to the internal iliac nodes.

• Lower third to the superficial inguinal nodes.

Structure

A stratified squamous epithelium lines the vagina and the vaginal cervix; it contains no glands and is lubricated partly by cervical mucus and partly by desquamated vaginal epithelial cells. In nulliparous women the vaginal wall is rugose, but it becomes smoother after childbirth. The rugae of the anterior wall are situated transversely; this allows for filling of the bladder and for intercourse. In contrast, the rugae on the posterior wall run longitudinally. This allows for sideways stretching to accommodate a rectum distended with stool and for the passage of the fetal head.

Beneath the epithelial coat is a thin connective tissue layer separating it from the muscular wall, which is made up of a criss-cross arrangement of involuntary muscle fibres. This muscle layer is ensheathed in a fascial capsule that blends with adjacent pelvic connective tissues, so that the vagina is firmly supported in place.

In old age the vagina shrinks in length and diameter. The cervix projects far less into it so that the fornices all but disappear.

Fig. 100 Coronal section of the uterus and vagina. Note the important relationships of the ureter and uterine artery.

The uterus (Figs 99, 100)

The uterus is a pear-shaped organ, 3in (7.5 cm) in length, made up of the fundus, body and cervix. The Fallopian (uterine) tubes enter into each superolateral angle (the cornu), above which lies the fundus. The body of the uterus narrows to a waist termed the isthmus, continuing into the cervix which is embraced about its middle by the vagina; this attachment delimits a supravaginal and vaginal part of the cervix. The isthmus is 1.5mm wide. The anatomical internal os marks its junction with the uterine body but its mucosa is histologically similar to the endometrium. The isthmus is that part of the uterus which becomes the lower segment in pregnancy.

The cavity of the uterine body is triangular in coronal section, but in the sagittal plane it is no more than a slit. This cavity communicates via the internal os with the cervical canal, which, in turn, opens into the vagina by the external os.

The nulliparous external os is circular, but after childbirth it becomes a transverse slit with an anterior and a posterior lip. The non-pregnant cervix has the firm consistency of the nose; the pregnant cervix has the soft consistency of the lips.

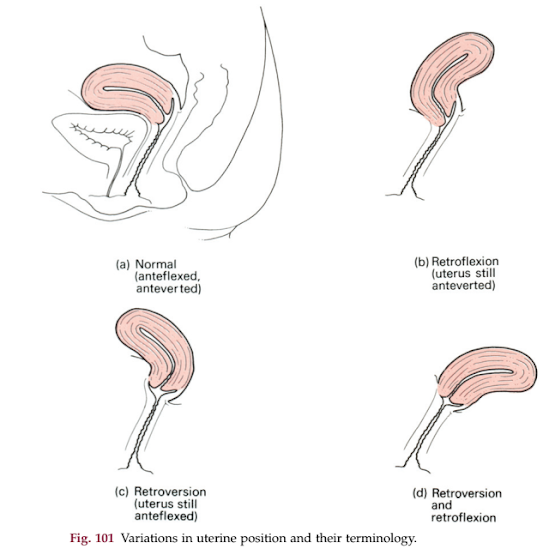

In fetal life the cervix is considerably larger than the body; in childhood (the infantile uterus) the cervix is still twice the size of the body but, during puberty, the uterus enlarges to its adult size and proportions by relative overgrowth of the body. The adult uterus is bent forwards on itself at about the level of the internal os to form an angle of 170°; this is termed anteflexion of the uterus. Moreover, the axis of the cervix forms an angle of 90° with the axis of the vagina – anteversion of the uterus. The uterus thus lies in an almost horizontal plane.

In retroversion of the uterus, the axis of the cervix is directed upwards and backwards. Normally, on vaginal examination the lowermost part of the cervix to be felt is its anterior lip; in retroversion, either the os or the posterior lip becomes the presenting part. In retroflexion the axis of the body of the uterus passes upwards and backwards in relation to the axis of the cervix.

Frequently these two conditions co-exist. They may be mobile and symptomless – as a result of distension of the bladder or purely as a development anomaly. Indeed, mobile retroversion is found in a quarter of the female population and may be regarded as a normal variant. Less commonly, they are fixed, the result of adhesions, previous pelvic infection, endometriosis or the pressure of a tumour in front of the uterus (Fig. 101).

Fig. 101 Variations in uterine position and their terminology.

Relations

• Anteriorly – the body is related to the uterovesical pouch of peritoneum and lies either on the superior surface of the bladder or on coils of intestine. The supravaginal cervix is related directly to the bladder, separated only by connective tissue. The infravaginal cervix has the anterior fornix immediately in front of it.

• Posteriorly – lies the pouch of Douglas, with coils of intestine within it.

• Laterally – the broad ligament and its contents (see below); the ureter lies approximately 0.5in (1.2 cm) lateral to the supravaginal cervix.

CLINICAL FEATURES

The most important single practical relationship in this region is that of the ureter to the supravaginal cervix. At this point, the ureter lies just above the level of the lateral fornix, below the uterine vessels as these pass across within the broad ligament (Fig. 102). In performing a hysterectomy, the ureter may be accidentally divided in clamping the uterine vessels, especially when the pelvic anatomy has been distorted by a previous operation, a mass of fibroids, infection or malignant infiltration.

The ureter is readily infiltrated by lateral extension of a carcinoma of the uterus; bilateral hydronephrosis with uraemia is a frequent mode of termination of this disease. The close relationship of the ureter to the lateral fornix is best appreciated by realizing that a ureteric stone at this site can be palpated on vaginal examination. (This is the answer to the examination question: ‘When can a stone in the ureter be felt?’)

Fig. 102 Lateral view of the uterus (schematic) to show the composition of the broad ligament, the relations of the ureter and uterine artery, and the peritoneal covering of the uterus (pink).

Fig. 103 Lymph drainage of the uterus and vagina

Blood supply

The uterine artery (from the internal iliac) runs in the base of the broad ligament and crosses above and at right angles to the ureter to reach the uterus at the level of the internal os (Fig. 102). The artery then ascends in a tortuous manner alongside the uterus, supplying the corpus, and then anastomoses with the ovarian artery. The uterine artery also gives off a descending branch to the cervix and branches to the upper vagina. The veins accompany the arteries and drain into the internal iliac veins, but they also communicate via the pelvic plexus with the veins of the vagina and bladder.

Lymph drainage (Fig. 103)

1 The fundus (together with the ovary and Fallopian tube) drains along the ovarian vessels to the aortic nodes – apart from some lymphatics, which pass along the round ligament to the inguinal nodes.

2 The body drains via the broad ligament to nodes lying alongside the external iliac vessels.

3 The cervix drains in three directions – laterally, in the broad ligament, to the external iliac nodes; posterolaterally along the uterine vessels to the internal iliac nodes; and posteriorly along the recto-uterine folds to the sacral nodes.

Always examine the inguinal nodes in a suspected carcinoma of the corpus uteri – they may be involved by lymphatic spread along the round ligament.

Structure

The body of the uterus is covered with peritoneum except where this is reflected off at two sites, anteriorly onto the bladder at the uterine isthmus and laterally at the broad ligaments. Anteriorly, the peritoneum is only loosely adherent to the supravaginal cervix; this allows for bladder distension. The muscle wall is thick and made up of a criss-cross of involuntary fibres mixed with fibro-elastic connective tissue.

The mucosa is applied directly to muscle with no submucosa intervening. The mucosa of the body of the uterus is the endometrium, made up of a single layer of cuboidal ciliated cells forming simple tubular glands which dip down to the underlying muscular wall. Below this epithelium is a stroma of connective tissue containing blood vessels and round cells.

The cervical canal epithelium is made up of tall columnar cells which form a series of complicated branching glands; these secrete an alkaline mucus that forms a protective ‘cervical plug’ filling the canal.

The vaginal aspect of the cervix is covered with a stratified squamous epithelium continuous with that of the vagina. The mucosa of the corpus undergoes extensive changes during the menstrual cycle, which may be briefly summarized thus: 1 first 4 days – desquamation of its superficial two-thirds with bleeding; 2 subsequent 2–3 days – rapid reconstitution of the raw mucosal surface by growth from the remaining epithelial cells in the depths of the glands; 3 by the 14th day the endometrium has reformed; this is the end of the proliferative phase; 4 from the 14th day until the menstrual flow commences is the secretory phase; the endometrium thickens, the glands lengthen and distend with fluid and the stroma becomes oedematous and stuffed with white cells.

At the end of this phase three layers can be defined:

1 a compact superficial zone;

2 a spongy middle zone – with dilated glands and oedematous stroma;

3 a basal zone of inactive non-secreting tubules.

With degeneration of the corpus luteum there is shrinkage of the endometrium, the arteries retract and coil, producing ischaemia of the middle and superficial zones, which then desquamate. It is probable that spasm of the vessels in the basal layer (which remains non-desquamated)

prevents the woman bleeding to death.

Only very slight desquamation and bleeding takes place in the mucosa

of the cervical canal.

The Fallopian tubes (Fig. 104)

The Fallopian, or uterine, tubes are approximately 4in (10 cm) long; they

lie in the free edge of the broad ligaments and open into the cornu of the

uterus. Each comprises four parts.

1 The infundibulum – the bugle-shaped extremity extending beyond the

broad ligament and opening into the peritoneal cavity by the ostium. Its

Fig. 104 The Fallopian tube, ovary and broad ligament (viewed from behind). mouth is fimbriated and overlies the ovary, to which one long fimbria actually adheres (fimbria ovarica).2 The ampulla – wide, thin-walled and tortuous.

3 The isthmus – narrow, straight and thick-walled.

4 The interstitial part – which pierces the uterine wall.

Structure

Apart from the interstitial part, the tube is clothed in peritoneum. Beneath this is a muscle of outer longitudinal and inner circular fibres. The mucosa is formed of columnar, mainly ciliated cells and lies in longitudinal ridges, each of which is thrown into numerous folds. The ova are propelled to the uterus along this tube, partly by peristalsis and partly by cilial action.

Fig. 104 The Fallopian tube, ovary and broad ligament (viewed from behind).

CLINICAL FEATURES

1 Note that the genital canal in the female is the only direct communication into the peritoneum from the exterior and is a potential pathway for infection (e.g. in gonorrhoea).

2 The fertilized ovum may implant ectopically, i.e. in a site other than the endometrium of the corpus uteri. When this occurs in the Fallopian tube it is called, according to the exact site, fimbrial, ampullary, isthmic or interstitial, of which the ampullary is the commonest and interstitial the rarest.

The ovary (Fig. 104)

The ovary is an almond-shaped organ, 1.5in (4cm) long, attached to the back of the broad ligament by the mesovarium. The ovary has two other attachments: the infundibulopelvic ligament (sometimes called the suspensory ligament of the ovary), along which pass the ovarian vessels, sympathetic nerves and lymphatics from the side wall of the pelvis, and the ovarian ligament, which passes to the cornu of the uterus.

Relations

The ovary is usually described as lying on the side wall of the pelvis opposite the ovarian fossa, which is a depression bounded by the external iliac vessels in front and the ureter and internal iliac vessels behind and which contains the obturator nerve. However, the ovary is extremely variable in its position and is frequently found prolapsed into the pouch of Douglas in perfectly normal women.

The ovary, like the testis, develops from the genital ridge and then descends into the pelvis. In the same way as the testis, it therefore drags its blood supply and lymphatic drainage downwards with it from the posterior abdominal wall.

Blood supply, lymph drainage and nerve supply

Blood supply is from the ovarian artery, which arises from the aorta at the level of the renal arteries. The ovarian vein drains, on the right side, to the inferior vena cava and, on the left, to the left renal vein, exactly comparable to the venous drainage of the testis.

Lymphatics pass to the aortic nodes at the level of the renal vessels, following the general rule that lymphatic drainage accompanies the venous drainage of an organ. Nerve supply is from the aortic plexus (T10 and T11); hence, referral of ovarian pain to the loin and groin. These are sympathetic (pain-conducting) afferent fibres. All these structures pass to the ovary in the infundibulopelvic ligament.

Structure

The ovary has no peritoneal covering; the serosa ends at the mesovarian attachment. It consists of a connective tissue stroma containing Graafian follicles at various stages of development, corpora lutea and corpora albicantia

(hyalinized, regressing corpora lutea, which take several months to absorb completely). The surface of the ovary in young children is covered with a so-called ‘germinal epithelium’ of cuboidal cells. It is now known, however, that the primordial follicles develop in the ovary in early fetal life and do not differentiate from these cells. In adult life, in fact, the epithelial covering of the ovary disappears, leaving only a fibrous capsule termed the tunica albuginea.

After the menopause the ovary becomes small and shrivelled; in old age, the follicles disappear completely.

The endopelvic fascia and the pelvic ligaments (Fig. 105)

Pelvic fascia is the term applied to the connective tissue floor of the pelvis covering levator ani and obturator internus. The endopelvic fascia is the extraperitoneal cellular tissue of the uterus (the parametrium), vagina, bladder and rectum. Within this endopelvic fascia are three important condensations of connective tissue which sling the pelvic viscera from the pelvic walls.

1 The cardinal ligaments (transverse cervical, or Mackenrodt’s ligaments), which pass laterally from the cervix and upper vagina to the side walls of the pelvis along the lines of attachment of levator ani, are composed of white fibrous connective tissue with some involuntary muscle fibres and are pierced in their upper part by the ureters.

2 The uterosacral ligaments, which pass backwards from the posterolateral aspect of the cervix at the level of the isthmus and from the lateral vaginal fornices deep to the uterosacral folds of peritoneum in the lateral boundaries of the pouch of Douglas, are attached to the periosteum in

Fig. 105 The pelvic ligaments seen from above.

Rectum

Uterosacral

ligament

Cardinal ligament

Pubocervical fascia

Pubic symphysis

Sacrum

Pouch of Douglas

Uterus

Bladder

front of the sacro-iliac joints and the lateral part of the third piece of the sacrum.

3 The pubocervical fascia extends forwards from the cardinal ligament to the pubis on either side of the bladder, for which it acts as a sling.

These three ligaments act as supports to the cervix of the uterus and the vault of the vagina, in conjunction with the important elastic muscular foundation provided by levator ani. In prolapse, these ligaments lengthen (in procidentia – complete uterine prolapse – they may be 6in (15 cm) long) and any repair operation must include their reconstitution.

Two other pairs of ligaments take attachments from the uterus.

1 The broad ligament is a fold of peritoneum connecting the lateral margin of the uterus with the side wall of the pelvis on each side. The uterus and its broad ligaments, therefore, form a partition across the pelvic floor dividing off an anterior compartment, containing the bladder (the uterovesical pouch), from a posterior compartment, containing the rectum (the pouch of Douglas or recto-uterine pouch).

The broad ligament contains or carries (Figs 102, 104):

• the Fallopian (uterine) tube in its free edge;

• the ovary, attached by the mesovarium to its posterior aspect;

• the round ligament;

• the ovarian ligament, crossing from the ovary to the uterine cornu

(see ‘The ovary’, page 156);

• the uterine vessels and branches of the ovarian vessels;

• lymphatics and nerve fibres.

The ureter passes forwards to the bladder deep to this ligament and lateral to and immediately above the lateral fornix of the vagina.

2 The round ligament – a fibromuscular cord – passes from the lateral angle of the uterus in the anterior layer of the broad ligament to the internal inguinal ring; thence it traverses the inguinal canal to the labium majus.

Taken together with the ovarian ligament, it is equivalent to the male gubernaculum testis and can be thought of as the pathway along which the female gonad might have descended, but in fact did not, to the labium majus (the female homologue of the scrotum). Compare this process with descent of the testis (page 131).

Vaginal examination

The relations of the vagina to the other pelvic organs must be constantly borne in mind when carrying out a vaginal examination. Inspection (by means of a speculum) enables the vaginal walls and cervix to be examined and a biopsy or cytological smear to be taken. Inspection of the introitus while straining detects prolapse and the presence of stress incontinence.

• Anteriorly – the urethra, bladder and symphysis pubis are felt.

• Posteriorly – the rectum (invasion of the vagina by a rectal neoplasm must always be sought after in this disease). Collections of fluid, malignant deposits, prolapsed uterine tubes and ovaries or coils of distended bowel may be felt in the pouch of Douglas.The female genital organs 159

• Laterally – the ovary and tube, and the side wall of the pelvis. Rarely, a stone in the ureter may be felt through the lateral fornix. The strength of the perineal muscles can be assessed by asking the patient to tighten up her perineum.

• Apex – the cervix is felt projecting back from the anterior wall of the vagina. In the normal anteverted uterus the anterior lip of the cervix presents; in retroversion, either the cervical os or the posterior lip are first to be felt.

Pathological cervical conditions – for example, neoplasm – can be felt, as can the softening of the cervix in pregnancy and its dilatation during labour. Bimanual examination assesses the pelvic size and position of the uterus, enlargements of ovary or uterine tubes and the presence of other pelvic masses.

The obstetrician can assess the pelvic size in both the transverse and anteroposterior diameter. Particularly important is the distance from the lower border of the symphysis pubis to the sacral promontory, which is termed the diagonal conjugate. If the pelvis is of normal size, the examiner’s fingers should fail to reach the promontory of the sacrum. If it is readily palpable, pelvic narrowing is present (see ‘Obstetrical pelvic measurements’, page 140).

Embryology of the Fallopian tubes, uterus and vagina (Fig. 106)

The paramesonephric (or Müllerian) ducts develop, one on each side, adjacent to the mesonephric (Wolffian) ducts in the posterior abdominal wall – they are mesodermal in origin. All these four tubes lie close together caudally, projecting into the anterior (urogenital) compartment of the cloaca.

One system disappears in the male, the other in the female, each leaving behind congenital remnants of some interest to the clinician.

In the male, the paramesonephric duct disappears, apart from the appendix testis and the prostatic utricle. In the female, the mesonephric system (which in the male develops into the vas deferens and epididymal ducts) persists as remnants in the broad ligament termed the epoöphoron, paroöphoron and ducts of Gärtner.

The paramesonephric ducts in the female form the Fallopian tubes cranially. More caudally, they come together and fuse in the midline (dragging, as they do so, a peritoneal fold from the side wall of the pelvis which becomes the broad ligament). The median structure so formed differentiates into the epithelium of the uterine body (endometrium), cervical canal and upper one-third of the vagina, which are first solid and later become canalized. The rest of the vaginal epithelium develops by canalization of the solid sinuvaginal node at the back of the urogenital sinus. This accounts for the differences in lymphatic drainage of the upper and lower vagina

(Fig. 103). The muscle of the Fallopian tubes, uterine body, cervix and vagina develops from surrounding mesoderm, so that remnants of the

Fig. 106 Development of the Fallopian tubes, uterus and vagina from the paramesonephric (Müllerian) ducts and the urogenital sinus (after Hollinshead) (a–c), and formation of the broad ligament (d). mesonephric duct system of the female are found in the myometrium, cervix and vaginal wall.

Developmental abnormalities of this system can easily be deduced. All stages of division of the original double tube may persist from a bicornuate uterus to a complete reduplication of the uterus and vagina. Alternatively, there may be absence, hypoplasia or atresia of the duct system on one or both sides.

Failure of canalization of the originally solid caudal end of the duct results, after puberty, in the accumulation of menstrual blood above the

Genital tract

Broad ligament

Parietal

peritoneum

Paramesonephric

ducts

(ii)

(i)

(d)

Fig. 106 Development of the Fallopian tubes, uterus and vagina from the paramesonephric (Müllerian) ducts and the urogenital sinus (after Hollinshead) (a–c), and formation of the broad ligament (d).The posterior abdominal wall 161 obstruction. First the vagina may distend with blood, then the uterus and then the tubes (haematocolpos, haematometra and haematosalpinx, respectively).

The posterior abdominal wall

The bed of the posterior abdominal wall is made up of three bony and four muscular structures. The bones are:

• the bodies of the lumbar vertebrae;

• the sacrum;

• the wings of the ilium.

The muscles are:

• the diaphragm – posterior part;

• the quadratus lumborum;

• the psoas major;

• the iliacus.

The diaphragm has been considered in the section on the thorax (see page 14).

The psoas must be dealt with in more detail because of the involvement of its sheath in the formation of a psoas abscess.

The psoas major arises from the transverse processes of all the lumbar vertebrae and from the sides of the bodies and the intervening discs of the T12 to L5 vertebrae. It passes downwards and laterally at the margin of the brim of the pelvis, narrowing down to a tendon which crosses the front of the hip joint beneath the inguinal ligament to be inserted, with iliacus, into the lesser trochanter of the femur (Fig. 107).

The psoas major, together with iliacus, flexes the hip on the trunk, or, alternatively, the trunk on the hips (e.g. in sitting up from the lying position). Psoas minor, absent in 40% of subjects, lies on psoas major and attaches to the iliopubic eminence.

Fig. 107 Psoas sheath and psoas abscess. On the right side is a normal psoas sheath; on the left side it is shown distended with pus, which tracks under the inguinal ligament to present in the groin.

CLINICAL FEATURES

1 The femoral artery lies on the psoas tendon in the groin, and it is this firm posterior relation of the femoral artery at the groin which enables it here to be identified and compressed easily by the finger.

2 The psoas is enclosed in the psoas sheath, which is a compartment of the lumbar fascia. Pus from a tuberculous infection of the lumbar vertebrae is limited in its anterior spread by the anterior longitudinal vertebral ligament, and therefore passes laterally into its sheath (psoas abscess), which may also be entered by pus tracking down from the posterior mediastinum in disease of the thoracic vertebrae. Pus may then spread under the inguinal ligament into the femoral triangle, where it produces a soft swelling (Fig. 107). Occasionally, in completely neglected cases, pus tracks along the femoral vessels, along the subsartorial canal and eventually appears in the popliteal fossa.

The retroperitoneal organs are: the pancreas, kidneys and ureters (which have already been considered), the suprarenals, the aorta and inferior vena cava and their main branches, the para-aortic lymph nodes and the lumbar sympathetic chain.

The suprarenal glands (Fig. 79)

The suprarenal glands cap the upper poles of the kidneys and lie against the crura of the diaphragm. The left is related anteriorly to the stomach across the lesser sac; the right lies behind the right lobe of the liver and tucks medially behind the inferior vena cava. Each gland, although weighing only 3–4 g, has three arteries supplying it:

1 a direct branch from the aorta;

2 a branch from the phrenic artery;

3 a branch from the renal artery.

The single main vein drains from the hilum of the gland into the nearest available vessel – the inferior vena cava on the right, the renal vein on the left. The stubby right suprarenal vein, coming directly from the inferior vena cava, presents the most dangerous feature in performing an adrenalectomy – the tiro should always choose the easier left side and leave the right to his chief.

The suprarenal gland comprises a cortex and medulla, which represent two developmentally and functionally independent endocrine glands within the same anatomical structure. The medulla is derived from the neural crest (neuroectoderm), whose cells also give rise to the sympathetic ganglia. The cortex, on the other hand, is derived from the mesoderm. The suprarenal medulla receives preganglionic sympathetic fibres from the greater splanchnic nerve and secretes adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine). The cortex secretes the adrenocortical hormones.

Nhận xét

Đăng nhận xét